Here's how far we've come with net neutrality

The FCC's ruling on net neutrality yesterday was the agency's most significant action in decades -- but it didn't come easy. It's something that's been discussed ever since Columbia Law professor Tim Wu coined the term net neutrality 2003, which, at its most basic level, refers to treating all web traffic equally. But the idea goes back to the age of the telegram, when the US government committed to treating all of those messages the same. As broadband access became more commonplace and the internet economy recovered from the dot-com bust of the '90s, Wu's net neutrality paper was a warning against the increasing power of ISPs. Now that we finally have a decent set of net neutrality rules, it's worth taking a look back to see how we got here.

The Communications Act of 1934

Yes, we're taking it way back. Title II of this act actually lays out the core of the FCC's net neutrality decision. It centers on the idea of a common carrier, or a regulated entity that transports goods to the public without discrimination, like telephone service in the US. That's directly opposed to the idea of a private carrier, which is only concerned with its own goods and can discriminate service as it sees fit. The FCC's decision yesterday reclassified broadband internet as a common carrier, giving it the ability to set rules on how ISPs handle their service.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996

This act complemented its older sibling by offering rules around internet access and fewer regulations when it came to media ownership. But when it comes to net neutrality, its most significant contribution is in making the (admittedly confusing) distinction between a "telecommunications service," which provides service directly to the public, and an "information service," which describes sending or retrieving information (basically, broadband internet access). Comcast, for example, fell under the telecommunications category for its phone service, but was then counted as an information service for its broadband offering.

The big difference? The FCC has a lot more regulatory power over the telecommunications category. The agency's net neutrality decision ended up reclassifying broadband internet access under the telecommunications umbrella.

2002: FCC classifies cable broadband as an information service

Basically clarifying its rules from the 1996 telecom act, the FCC ruled in 2002 that all cable modem traffic counted as an information service.

2003: Tim Wu gives us 'net neutrality'

Wu's seminal paper, "Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination," dove into the pitfalls behind classifying broadband as an information service. Among other things, he brought up the notion that the openness of the internet allows for innovative ideas and services ---something that could be endangered if broadband providers were able to manipulate speeds, or prioritize certain types of traffic. Not surprisingly, the concept also became a political flashpoint. It won the support of people who wanted to maintain the freewheeling nature of the net, but also terrified those who were concerned about government overregulation. The back-and-forth between those camps will likely continue for years.

2003-2009: Broadband internet access goes mainstream

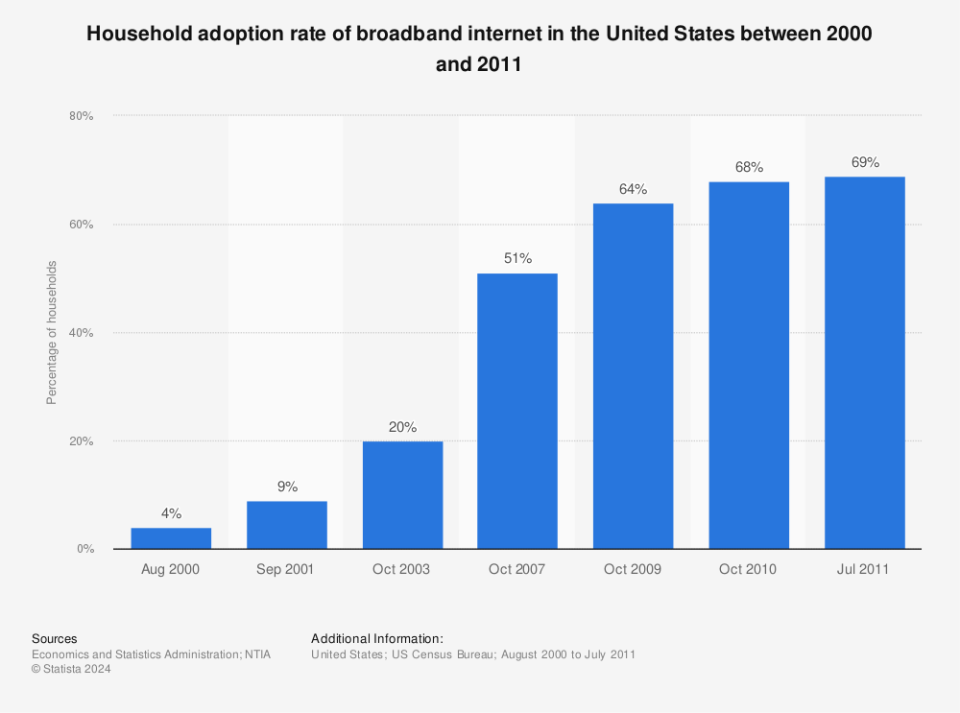

Young folks might not realize this, but it used to be that broadband internet access was a luxury, and not just a given in most homes. (And let's not even get into what life was like before decent WiFi.) According to data from the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, broadband went from just 4 percent of American households in 2000 to 20 percent in 2003. By 2007, it reached 51 percent of homes, making it the dominant type of internet access in the US, and it's hovered around 70 percent of households since 2010.

2005: FCC offers weak suggestions on keeping the net open (without regulation)

The FCC's first major move in keeping the internet open was pretty weak: It was just a set of policy guidelines that it would keep in mind for future decisions. Among them, the agency noted that consumers have a right to access legal information, use the devices and services they want and have competition among their broadband providers. But really, it was nothing more than a strongly worded recommendation, since it didn't involve any regulatory consequences.

2005: DSL gets reclassified as an information service

This wasn't a huge move, especially since cable internet was the better broadband choice for most consumers, but changing DSL's designation to an information service also made it difficult for the FCC to effectively regulate it.

April 2006: Save the Internet coalition forms

Bloggers, nonprofits and web companies joined together for this first stab at net neutrality activism, though it would be years before they saw any major results. Some of Save the Internet's petitions managed to get as many as 1.9 million signatures, but that was also before many people had smartphones and depended heavily on the web.

2006: Lawmakers fail to rule on net neutrality (again and again)

Between the Internet Freedom and Nondiscrimination Act, and the Network Neutrality Act, 2006 was the year when politicians started to take the concept of the open web seriously. The only problem? These early bills went nowhere.

2007: Comcast starts throttling BitTorrent traffic

Comcast (not surprisingly) ended up being one of the first ISPs to find itself in a net neutrality snafu. It was found to be throttling BitTorrent traffic on its network, which led to several class action lawsuits from customers (it ended up settling one suit for $16 million in 2009, but admitted no wrongdoing).

August 2008: FCC tries to put the smackdown on Comcast

Comcast's customers weren't the only ones annoyed by its BitTorrent throttling. The FCC also upheld a complaint against the ISP and called for it to stop throttling traffic against file-sharing services by 2008. That led Comcast to make nice with BitTorrent, even though it still planned to manage traffic on its network. The FCC didn't impose any fines, but it hoped to make an example of Comcast by making it reveal the details of how it managed its network.

April 2010: Comcast wins appeal against FCC, court rules agency can't enforce net neutrality

Even though the FCC wasn't asking Comcast for much, the telecom still managed to appeal against the agency's earlier ruling. A Washington, DC, court of appeals ended up squashing the FCC's order against Comcast, and it also ruled the agency doesn't have the authority to force companies to keep their networks open.

December 2010: FCC passes stronger net neutrality rules

By this point, the FCC realized it needed to be on stronger legal ground when it came to enforcing net neutrality. It announced a new set of rules that would place stronger regulations on wired broadband, which called for ISPs to disclose their management practices and forbid them from blocking lawful services on their networks. The agency took a lighter touch with mobile broadband, which it believed needed "measured steps" when it came to regulation. Despite the big changes, many net neutrality proponents believed the rules didn't go far enough.

January 2014: Court rules in favor of Verizon, strikes down FCC's net neutrality rules

After fighting against the FCC's open internet plans for years, Verizon scored big when a DC circuit court ruled that the FCC had no authority to enforce net neutrality rules. The reason? ISPs didn't count as common carriers, which gave the agency little regulatory powers over them. That's something the FCC managed to fix with its latest net neutrality ruling.

February 2015: FCC makes its biggest net neutrality ruling ever

After several attempts at keeping the internet open with little regulation, the FCC finally flexed its muscles a bit with this week's ruling. It classifies both wired and wireless broadband as a Title II common carrier, giving it more regulatory power in the process. The new rules are basically an evolved form of what the FCC pursued before -- they'll ban ISPs from forcing companies to pay more for faster access to their customers, for example -- but now the agency has the legal standing to effectively enforce them.

[Photo credits: Mark Wilson/Getty Images (Top photo); Greg Richards/BKLYN Info Commons (Slow lane protest); Knight725/Flickr (Comcast building); JeepersMedia/Flickr (Verizon store)]