Exoplanet census suggests Earth really is special

Pale Blue Dot FTW!

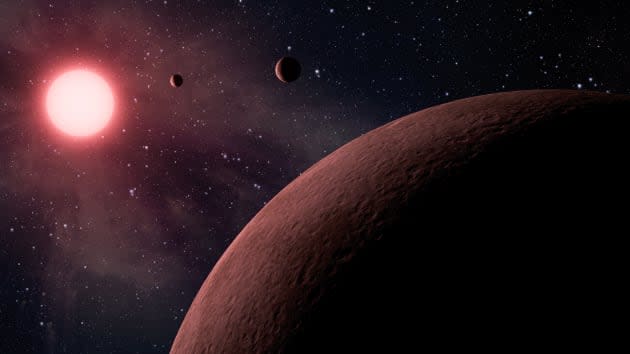

There are an estimated 700 million trillion terrestrial planets in the observable universe. Among them, Earth may very well be one of a kind according to a new study from Uppsala University in Sweden. Astronomer Erik Zackrisson and his team have been running computer simulations to model all of the terrestrial planets that are likely to exist in the universe. The probabilistic exoplanetary statistics that they've gleaned from these simulations could potentially upend the Copernican principle and will soon be published in The Astrophysical Journal (it's currently up on arXiv).

They started with all the data we currently have on exoplanets. Then they crafted a computer model -- essentially a miniature digital copy of the early universe -- and fed that exoplanet data, as well as the laws of physics as we know them, into the model. Fast forward 13.8 billion simulated years and the team found that of those 700 quintillion possible exoplanets, a vast majority of them look nothing like Earth. Most were far older, in fact, so Earth's relatively young age and position within the Milky Way galaxy could make it unique.

That said, "It's certainly the case that there are a lot of uncertainties in a calculation like this. Our knowledge of all of these pieces is imperfect," study co-author Andrew Benson from the Carnegie Observatories in California told Scientific American. Exoplanets are still a fairly new field of study in astronomy and, until the launch of the Kepler and Spitzer Space Telescopes, we knew practically nothing about them. Heck, even with the Kepler, the data on exoplanets has skewed heavily towards super-earth-sized planets orbiting close to their stars. We know much less about smaller exoplanets that orbit farther away since they're much harder for Kepler to spot. Plus, "everything we know about exoplanets is from a very small patch in our galaxy," Zackrisson told SA, which confounds the results even further.

In the end, however, the team remains confident that, despite our incomplete knowledge of physics and exoplanets, their results are correct within an order of magnitude -- which is pretty darn accurate given the scope of the study. "Whenever you find something that sticks out," Zackrisson says, referring to the rise of intelligent life on Earth. "That means that either we are the result of a very improbable lottery draw or we don't understand how the lottery works."