Facebook’s two-factor ad practices give middle finger to infosec

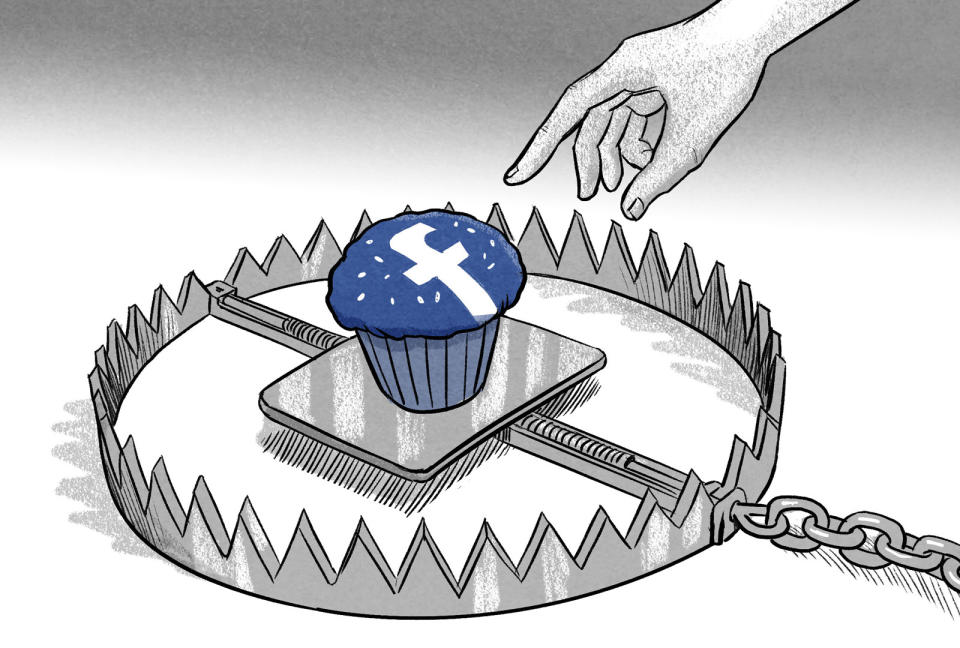

Using our security information for commercial purposes ought to be illegal.

We've all encountered security questions asking where we went to school, our favorite color or food, our first concert, and the ubiquitous "mother's maiden name." Imagine a world where on one screen you carefully chose Stanford, red, spaghetti and so on, and on the next you were shown ads for Italian restaurants, red shoes, and jobs for Stanford grads.

Seems like an insane violation, right? I mean, it stands to reason that we expect that the information we type to secure our online accounts and apps is private and safely guarded.

Me giving Facebook my phone number for 2FA is not the same thing as me opting-in to advertiser messaging, but I bet that's how it is spelled out in the terms of service... Wow. https://t.co/4ekfqT79G8

— Jeremy Vanderlan (@jvanderlan) September 26th, 2018

Not so, we learned this past week, when amid all the chaos of the news cycle we're desperately trying to stay on top of, it came to light that Facebook admitted to handing over people's phone numbers they provided for two-factor security purposes.

In response to the fact that no one knew about this, the company made it seem as though this practice was in a policy somewhere that people could've learned about and avoided but didn't. "We are clear about how we use the information we collect," a Facebook spokesperson said in a statement to press, "including the contact information that people upload or add to their own accounts. You can manage and delete the contact information you've uploaded at any time."

There is no part of Facebook's own Data Use Policy that states the company uses information provided for security purposes under "Information We Collect," nor does security information make an appearance in "How Do We Use This Information?" -- neither does the section on security.

Facebook's Data Use Policy security section only says, "We use the information we have to verify accounts and activity, combat harmful conduct, detect and prevent spam and other bad experiences, maintain the integrity of our Products, and promote safety and security on and off of Facebook Products." That's it.

To be absolutely clear, there's nothing in Facebook's documentation about making ad dollars off of your security info. Nor is there anything anywhere that told users their two-factor phone numbers provided for security went into a database for ad targeting. Not that it would make any of this OK at all if Facebook had come back to press saying, "Here's our policy on doing whatever we want with things you gave us for protecting your own security."

Facebook told press this nontransparent betrayal of trust is to make people's experience better on the social network. If you don't like it, now that it's too late, the company said your only option is to not use "phone number based 2FA."

This is Facebook telling the public that if they don't want their security information used for the purposes of advertisers stalking them, users should not use two-factor in a way that is (for many) the only way they know how.

This all came out when Gizmodo verified that Facebook has been taking our "shadow profile" information -- secret dossiers it makes about us with info we don't give the company and can't see or control -- and handing it to its unknown pool of, probably, poorly secured data dealers. But we expected that.

It flies right in the face of what the company's security chief said back in January when infosec folks complained about giving Facebook their phone number for two-factor and then got SMS spammed with News Feed notifications via the number they provided. People who responded to these surprising and unwanted notifications found that their responses were being posted on Facebook.

"The last thing we want is for people to avoid helpful security features because they fear they will receive unrelated notifications," wrote then-CSO Alex Stamos. For those keeping track, he's the same CSO who was active during the massive Facebook hack the company just admitted to, and he also ran Yahoo security during its record-setting breach of 500 million accounts. It's probably important to keep track of such things. But I digress.

Until this past May, phone numbers were the only way Facebook users could add the extra layer of security to their accounts. During that rollout, Facebook Security Communications Manager Pete Voss would not tell Wired how many people use two-factor on the social network. "I can just say that we've gotten the feedback that people want it to be easier, people do take security seriously," he said.

Prior to that, in January Facebook added the two-factor option of security keys (like the Yubico) for users but still told them they'd need to hand over a phone number as well.

In a 2017 survey Duo Labs found that the use rate for two-factor was 28 percent, with most (85.8 percent) saying their preferred method was SMS (phone number) notification. At the Usenix Enigma 2018 security conference in California this past January, a Google engineer revealed that 10 percent of Gmail users have two-factor enabled. So we might estimate that perhaps out of every 10 people there are between one and three who use two-factor, with most of them preferring the default SMS method.

Now let's look at a Facebook number: the 50 million people whose accounts we just found out were exposed in the company's jaw-dropping 2017-2018 authentication token snatch and grab. So if even just one in 10 used 2FA and we used Duo's 85 percent for guessing how many of those use SMS... 4.25 million Facebook users who thought they gave Facebook a phone number in good faith now risk being stalked by the company's pet advertisers. I'm sure there were even more ad targets scooped into the mix when Facebook made 2FA mandatory for "some" Page managers in August.

This, however, cuts deep in the worlds of both security and the secured. Taking people's security stuff and trading it (or maybe renting it, as Facebook is keen to avoid the word "selling") is the infosec equivalent of poisoning a water supply. It establishes Facebook as a threat to the core principles of security. It is a betrayal of trust that left many in the security profession speechless with anger -- and tech lawyers furiously disgusted. And worried. Very worried about what this means for everyone.

Plainly put, people will be discouraged from using 2FA, and this is a net loss for everyone. They'll see things like "You Gave Facebook Your Number For Security. They Used It For Ads." And despite the cautions of that article, people now know that big companies like Facebook are doing this unapologetically, and they will be safe in assuming that other companies do this as well.

We all know that humans are crap at making good passwords, that everything runs on passwords and that not enough people use password managers. Two-factor SMS is a tacked-on solution and it's not the best, but it's battle-tested as being something that reduces risk.

I mean, talk about undoing years of hard work convincing people to secure their accounts.