IBM's latest quantum computer is a 20-qubit work of art

The glass exterior was designed by Goppion, a Milan-based manufacturer of high-end museum display cases.

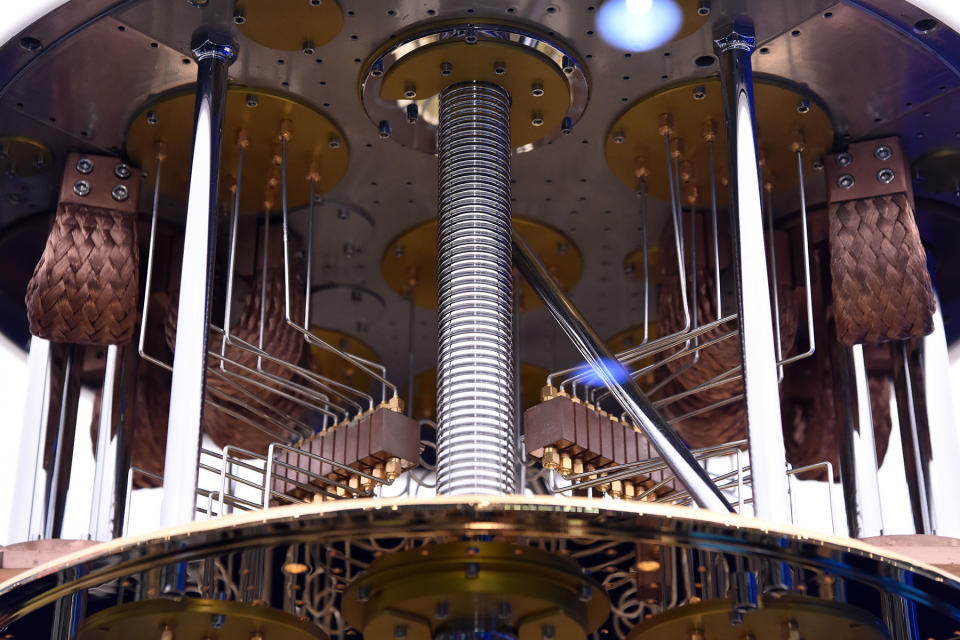

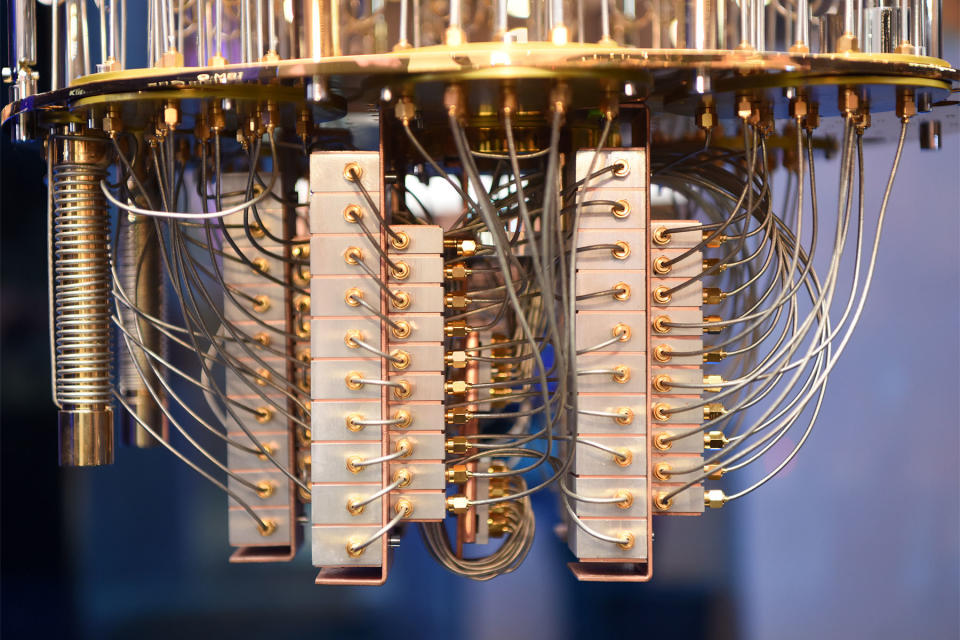

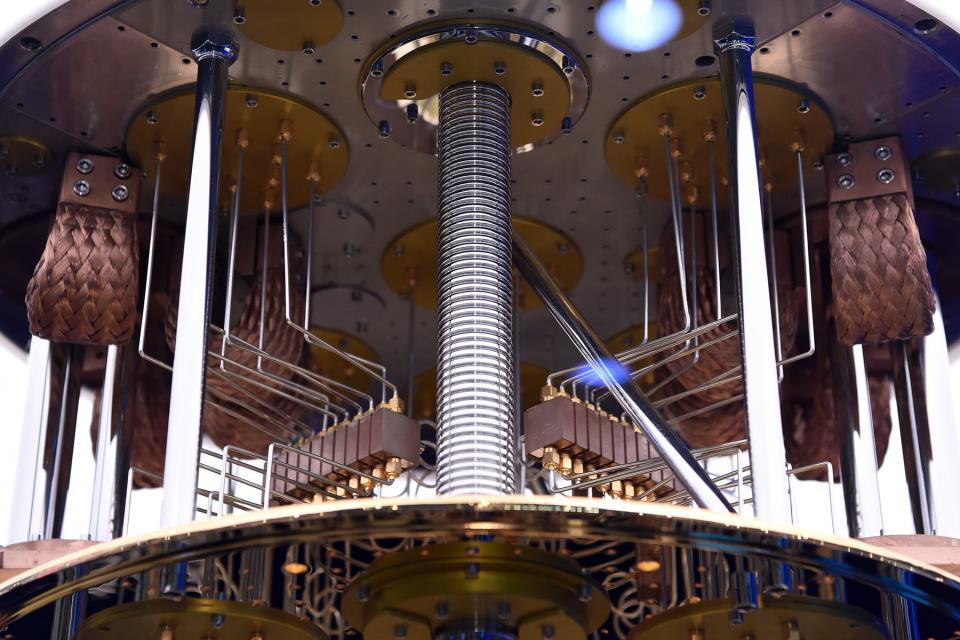

Last year, IBM hauled a 50-qubit quantum computer to CES. Or, rather, it brought the eye-catching bits -- an intricate collection of tubes and wires that resembled a steampunk chandelier -- and left the more cumbersome cooling and power-management parts at home. The complete system, housed at a research lab in Yorktown Heights, New York, was spread out over a large room. It was a functional but totally inelegant design, according to Bob Sutor, vice president of IBM Q Strategy and ecosystem.

"Imagine a car," he told Engadget, "but take off the shiny exterior of the car. And then move the battery over to one side. Instead of having a very tightly integrated set of electronics in the powertrain and things like that, start pulling them apart into pieces and just kind of spreading them all around the car. It might still be functional. But it's not a great design [in terms of] integration, right?"

Roughly one year ago, IBM set out to make something better: a fully integrated system that was modular, easily upgradable and optimized for quantum computing. The result, which is being unveiled at CES today, is called the IBM Q System One.

And it looks wild.

All of the parts are nestled inside a 9-foot cube made with half-inch-thick borosilicate glass. The front and back "doors" can open simultaneously, giving engineers access to the quantum computer at the front and the various cooling and control modules hidden behind a rear panel. Opening both doors would cause the cube to tip over, rather like a sloping parallelogram -- so the cube is also reinforced by a series of independent aluminum and steel frames. These ensure structural integrity while minimizing vibrations and other potential interference.

This jaw-dropping look was dreamt up by Map Project Office, an industrial design firm that has worked with Sonos, Honda and Kano before, and Universal Design Studio, an architecture and interior design practice based in London. The glass cube was handled by Goppion, a Milan-based manufacturer that has designed high-end display cases for the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, the Crown Jewels at the Tower of London and more.

The glass shell allows IBM to tightly control the temperature inside.

It's no surprise, therefore, that the quantum computer looks like a piece of art.

The glass shell allows IBM to tightly control the temperature inside. That's critical for the quantum chip -- which has to be kept at around 10 millikelvins, or a fraction above absolute zero -- and the supplementary electronics that read the board. Any vibrations or unexpected changes in temperature can render a project useless. IBM's new design should, in theory, reduce the number of errors that occur while running experiments and, therefore, make the system more reliable for IBM's various research and commercial partners.

If you need a refresher, quantum computing leverages quantum bits, known as qubits, to process potentially complex tasks. Unlike traditional bits, which can be set to "one" or "zero," qubits can take on both values at once, or a proportional mixture of the two (scientists call this "superposition"). If you have two qubits, you can test four possible outcomes simultaneously (0-0, 0-1, 1-0, 1-1). Qubits are also aware of each other -- a phenomenon known as "entanglement" -- which helps the computer to arrive at an answer.

Quantum computing has the power, therefore, to trump traditional computers that test possible solutions one-by-one. It could revolutionize health care -- as doctors search for effective medicine -- artificial intelligence, cryptography, financial modeling and weather simulation. That's what early researchers are hoping, anyway.

IBM is imagining a world where quantum computers sit neatly beside traditional PCs and server farms.

The IBM Q System One contains a fourth-generation 20-qubit machine. That might sound feeble -- Google announced a 72-qubit machine last March -- but it's the quality, not quantity that matters, according to Sutor. IBM wanted to focus on error mitigation, and overall reliability, before increasing the system's power. "We've been focusing on the architecture and the layout of the [quantum] chip," he said. "We've been looking at all the factors that go into building a quantum chip that will allow us to extend to more and more qubits, and have them run efficiently with fewer errors."

With the Q System One, IBM is imagining a world where quantum computers sit neatly beside traditional PCs and server farms. One day, a company might have many "cubes" stacked horizontally or vertically in a room. Or the necessary equipment to change and upgrade the innards of a single system.

Quantum computing is, for the most part, uncharted territory. And while the technology is still in its infancy, IBM is trying to show what a mature product can, or should, look like. The Q System One is experimental hardware -- you can't buy one in Walmart -- but the company has tried to package it up like the original iMac; beautiful and self-contained, with an obvious window to peek inside and marvel at what the engineers have put together.

It's hoped that creating something beautiful will maintain, and possibly increase, interest in the technology. It also gives people something real and tangible to admire. That's important while quantum computing is stuck in a murky research period. Work is clearly being done -- experiments are being run and academic papers are getting published -- but many of the technology's advantages are still theoretical. Quantum computers aren't breaking financial encryption, for instance, or running complex weather simulations just yet. If you're not keeping up with the latest research, it's hard to know if quantum computing is real, or complete vaporware.

New hardware like the Q System One, however, is easy to appreciate. For one, it's massive -- a stark and refreshing contrast to smartphones and laptops, which are constantly getting smaller. The glass case and steel beams won't be to everyone's tastes, but they show a clear evolution and progression from what the company has built and exhibited before.

The Q System One at CES is, unfortunately, just a model. It's 7.5 feet on each side, rather than 9, and doesn't have the rear panel that hides the various cooling, power and system monitoring components. IBM also removed the protective cover that normally surrounds the quantum computer so attendees can gawp at the pipes and wires that keep the qubits cool.

IBM has a "fully operational" System One prototype in Yorktown Heights, according to Sutor, that is already conducting experiments. "It's safe to say this is the best running quantum computer we have ever built, by every metric," he said. "And it's being used by the research staff right now."

Later this year, the company will open a "Quantum Computation Center" in Poughkeepsie, New York, for an upgraded version of the Q System One. (The team is deciding whether to modify the unit in Yorktown or build another from scratch.) In a press release, IBM said the city was "one of the few places in the world with the technical capabilities, infrastructure and expertise to run a quantum computation center, including access to high-performance computing systems and a high availability data center needed to work alongside quantum computers."

"This is the best quantum computer we've ever built."

Most of IBM's clients, known collectively as the Q Network, won't see the physical system every day. They will, however, benefit from the cube's improved stability and modular design. "We will ultimately make clients who are using these systems much happier," Sutor said. "Particularly as we upgrade and increase the power of the system."

The latest Q Network members include ExxonMobil, an energy giant, and CERN, the European research organization behind the Large Hadron Collider. "We're seeing core science starting to take advantage and understand this," Sutor said, "and business organizations trying to understand how it's relevant. So that's exciting."

The Q System One is a small, but significant milestone for quantum computing. It will be many years, however, before the technology has a perceptible impact on our lives. "It's terribly fun to say, 'Oh, in a year we'll do this,' and whatever," Sutor said. "But the fact of the matter is that this quantum-computing stuff is new. It's different and there are lots of scientific and technological innovations which must occur to really advance this. And I know from being a mathematician that you can't have scientific breakthroughs on demand."