‘Good Omens’ and the art of avoiding Armageddon

Neil Gaiman and Jon Hamm like the planet just how it is, thanks very much.

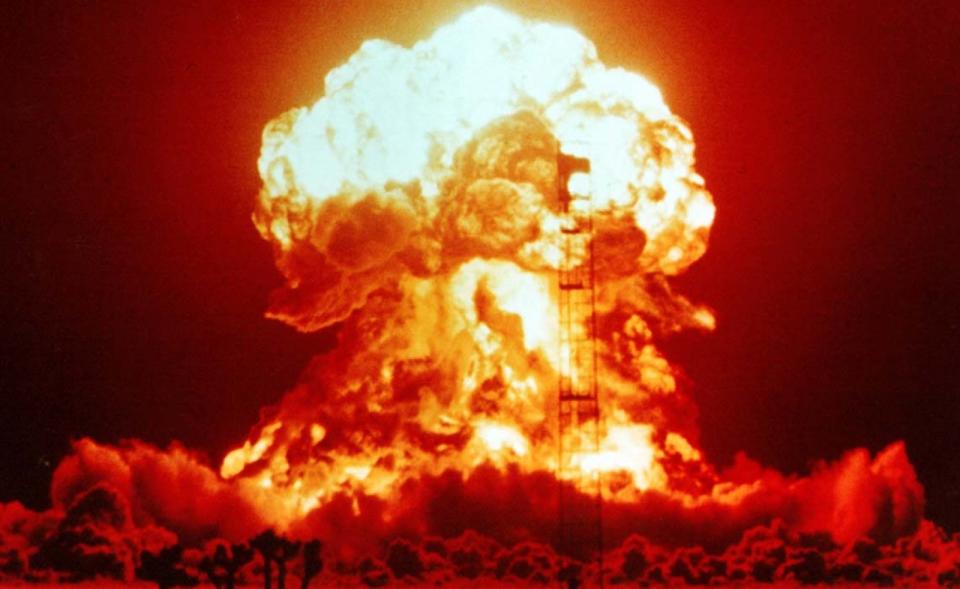

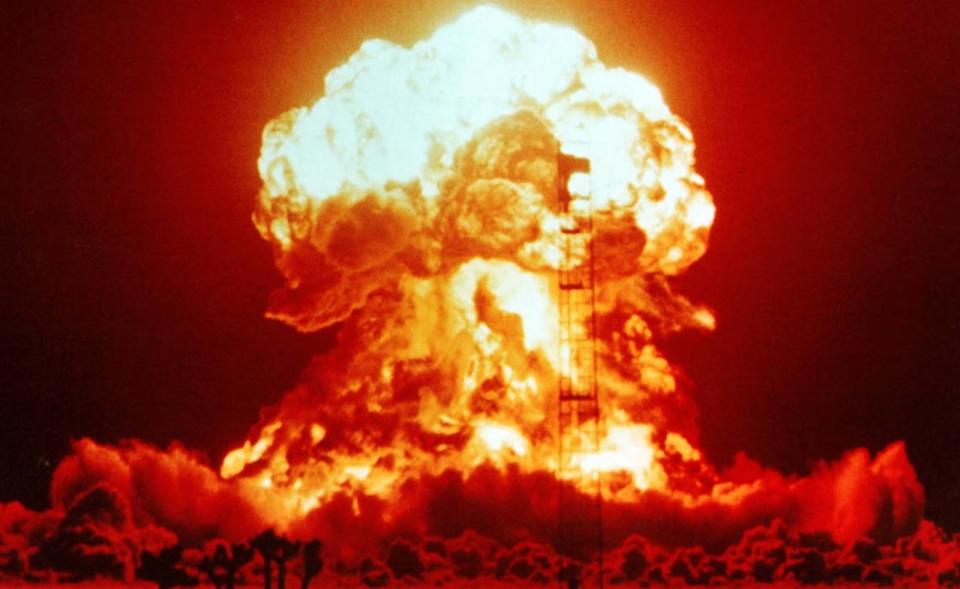

The world will end one day. That's a plain fact; what's unknown is the exact manner in which humanity will be erased from existence. Whether the oceans will boil us from below like a massive earthenware lobster pot, or a nuclear holocaust will strip the planet bare, or biological warfare will infect our evolutionary timeline, is anyone's guess, and everyone has a theory.

Few actually see the planet reaching its natural conclusion, when it's consumed by the Sun's billion-degree death rattle. There's constant, global anxiety about the advent of a man-made apocalypse, and this fear is especially present in the technology sector, where averting a manufactured Armageddon is driving innovation in clean energy, electric vehicles and space flight. At the same time, decades-old technological breakthroughs in atomic activity have forced the world into a fragile nuclear balance that feels on the brink of splintering. Again.

"We've been very, very close to seeing the use of nuclear weapons," Beatrice Fihn, Executive Director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, said during a panel at SXSW 2019. "We have more nuclear-armed states than ever. We have a very rapidly changing security environment in the world, where things do not look like they did during the Cold War. It's not two blocs anymore, it's a very fast-paced, quite messy conflict that's getting much more unclear."

"We're also standing in front of a huge technological development."

Modern nuclear politics are tense. President Donald Trump has pulled the US out of agreements such as the Iran nuclear deal and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia, while trading threats with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. Meanwhile, the most worrisome atomic battleground in the world lies between India and Pakistan, whose leaders are locked in a fragile standoff.

"And then we're also standing in front of a huge technological development," Fihn said. "Artificial intelligence, cyber warfare, that can very quickly change every security calculation we've done so far."

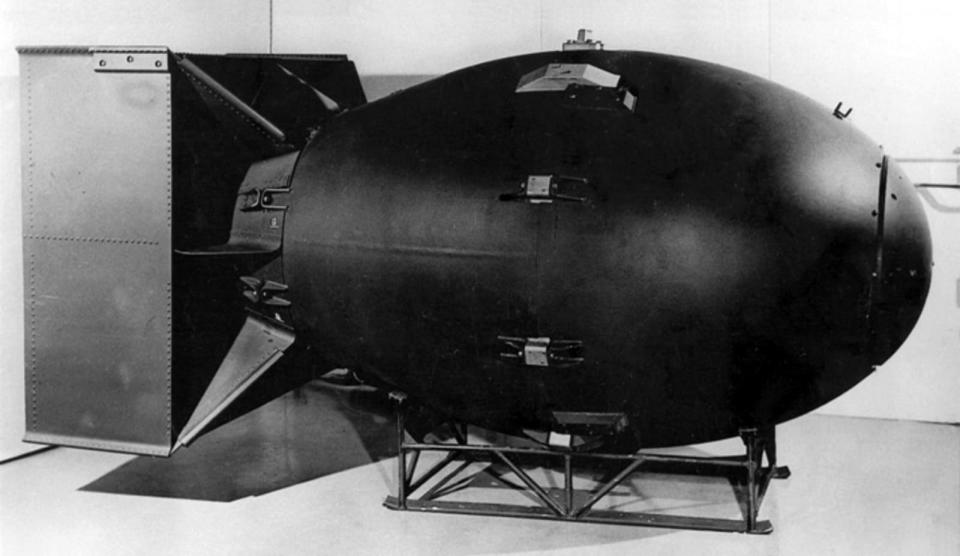

Treaties have helped curtail the proliferation of atomic weapons since the Cold War, but today's nuclear weapons are a far cry from the 10,000-pound beasts that the US dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, killing more than 200,000 people and effectively ending World War II.

Mareena Robinson Snowden is the Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and she previously worked for the National Nuclear Security Administration, which oversees the US' nuclear arsenal, including refurbishment and modernization efforts. "I think that we do ourselves a disservice by characterizing the weapons as 'old,' because they're not old," Robinson Snowden said. "They are very modern systems and there are very smart scientists and engineers whose job it is to work on these systems. When you think of a nuclear weapon, do not think of Little Boy and Fat Man, as big as this projector that we're throwing out of a jumbo jet. That's not the systems that we're talking about. We're talking about very advanced, very small systems."

"We're talking about very advanced, very small systems."

As the doomsday clock ticks closer to midnight, the broader culture responds. During the Cold War, for instance, a new industry popped up shilling in-home fallout shelters and nuclear-strike accoutrements for the entire family. Atomic paranoia shaped an entire era of American history -- the Atomic Age, the nuclear family, Dr. Strangelove -- and seeped into fiction worldwide.

In Japan, comics and cartoons were suddenly infused with imagery of blistered, burning land, orphaned children and incurable sickness as artists attempted to capture the horror of nuclear bloodshed. Anime and manga found its footing in these themes, paving the way for globally influential creators like Hayao Miyazaki.

In modern times, Western atomic anxiety is expressed in the resurgence of prepper culture, while folks like Elon Musk have achieved godking status for promising to one day, maybe, offer an escape from the planet entirely.

As the nuclear apocalypse looms over popular culture and consciousness, acclaimed fantasy author Neil Gaiman is preparing to launch Good Omens, a six-episode Amazon Prime series based on the 1990 novel he wrote in partnership with Terry Pratchett. Good Omens doesn't imagine an Earth ravaged by nukes, but instead sees it scheduled for destruction by immutable demonic forces. The apocalypse is inevitable and ineffable, but that doesn't stop a group of informed folks from trying to thwart it anyway, much as we're doing in reality.

"Somebody sent me a message on Twitter yesterday asking how I managed to cunningly set up the time frame of this so incredibly well, so that at the exact point that Good Omens came out would be a point where Armageddon would actually feel real and possible," Gaiman told Engadget at SXSW. "There was a line that Terry and I put into the book when we wrote it ... about how unlikely an apocalypse was at that time when everybody was getting along so incredibly well. I, frankly, given the choice, would much rather have had to put that line into the show."

Good Omens is proof of humanity's obsession with The End. It closely follows the entities that hold the fate of the planet in their hands, riffing on humanity's history of atomic warmongering and militaristic posturing. It's a story built on the idea that people have the power to end the world. And to save it.

"One of the things that I love about Good Omens is that it is life-affirming and world-affirming," Gaiman said. "It actually suggests very strongly that the avoidance of war is a much more important thing than war."

The chances of a nuclear catastrophe, accidental or purposeful, increase exponentially with each warhead in existence. However, the weapons themselves aren't the actual problem -- the fact that we know how to make them is. US scientists released the nuclear-knowledge genie in 1945 and there's no going back; we've reached a point where no country's leader will believe another when they promise to destroy their stockpiles.

In this case, mistrust is the harbinger of Armageddon, not nuclear warheads.

Here's where Good Omens really drives the lesson home. The story revolves around the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley, two creatures from opposing sides of an ageless and endless war. They live on Earth for eons and, once the devil's plan becomes clear, they work together to save humankind from annihilation. The message isn't about dismantling nuclear warheads, but breaking down the barriers preventing us from seeing our common ground.

"It's a very nice message, too, when you have the two central characters, these celestial beings, they don't have any real dog in the fight, other than the fact that they've been around long enough and hung around humanity enough that they kind of like it," said Jon Hamm, who plays the archangel Gabriel on Amazon's version of Good Omens. "And they realize that what we've done down here is actually sort of a lovely thing and they'd rather not burn it all down. I feel the same way. I'd rather not burn it all down."

"Me too," Gaiman responded. "I really like it."

Good Omens replaces military leaders with gods and demons, and a nuclear Armageddon with fated doom, but the stakes are just as high. Atomic weapons technology is the sole property of humankind; we've constructed the means to our own end and duplicated it thousands of times over. With nuclear bombs, humans have the ultimate, fabled power of god or the devil.

Of course, we also have the power to not destroy the world.

"You can not slice any part of Good Omens through without hitting it, just the idea that actually the world is a really good thing," Gaiman said. "It's a really good place and sticking around on it is infinitely preferable to any way of ending it or damaging it that proves a point. ... That, in many ways, is the biggest challenge. How do you make the averting of an apocalypse as dramatically interesting as an apocalypse?"

Gaiman, at least, has a theory.