Did Frankenstein go to the Moon?

A Manchester textiles company may have played a pivotal role in spacesuit design.

There's a mystery at the heart of the first Moon landing. And no, it's not whether the whole thing was staged. Instead, historians are wondering whether a small company in Manchester helped NASA design its iconic Apollo 11 spacesuit.

Frankenstein & Sons was founded in 1854 and operated out of the Victoria Rubber Works in Newton Heath, Manchester.

During the Second World War, it started producing highly sophisticated survival gear for aircrew. For a while, Britain protected some of its convoys with Hawker Hurricane fighters that launched from merchant vessels retrofitted with rocket-propelled catapults. Once the pilots had intercepted the enemy -- typically long-range reconnaissance planes -- they had to eject and wait in the sea for an allied forces pickup. Frankenstein & Sons is thought to have developed a leather-based 'immersion suit' and, later, a fabric-based alternative that stopped pilots from catching hypothermia while they waited for a pickup in the icy water.

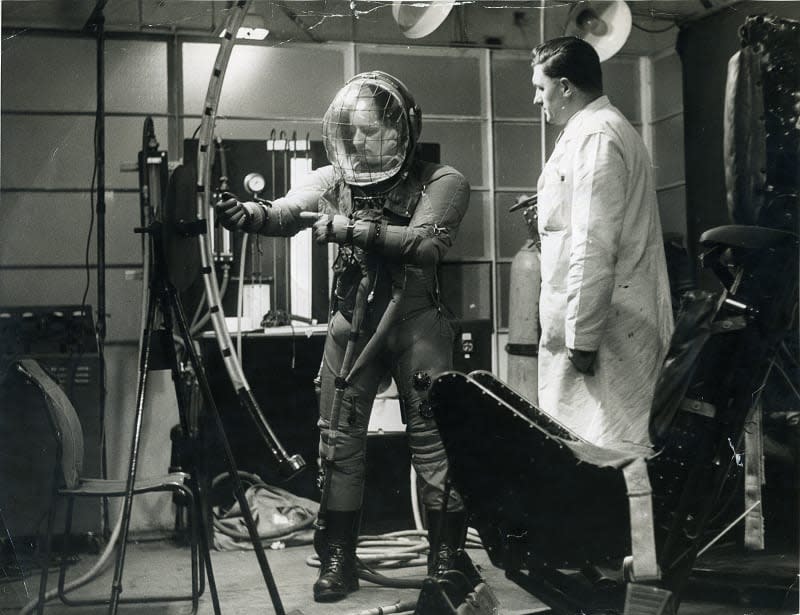

Over time, planes were developed that could fly higher and higher above the ground. The Royal Air Force (RAF) Physiological Laboratory explored full pressure suits -- a complete outfit that offers an artificial environment for the wearer -- in the 1940s. The outfits were preferable to full cockpit pressurisation because they had a smaller weight impact and could protect the pilot if the cockpit was pierced by enemy fire and -- worst case scenario -- required evacuation. The work was developed further with three companies in the 1950s: Siebe Gorman, BWT (Baxter, Woodhouse and Taylor) and Frankenstein & Sons.

All of the prototype suits were tested by the RAF's Institute of Aviation Medicine (IAM) and the Royal Aircraft Establishment's (RAE) Mechanical Engineering department in Farnborough.

As the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester explains, these suits were designed to inflate and stabilize the pressure felt by the pilot in the event of decompression inside the cockpit. Many of them looked like rudimentary spacesuits because they were designed for similar levels of elevation and atmospheric problems.

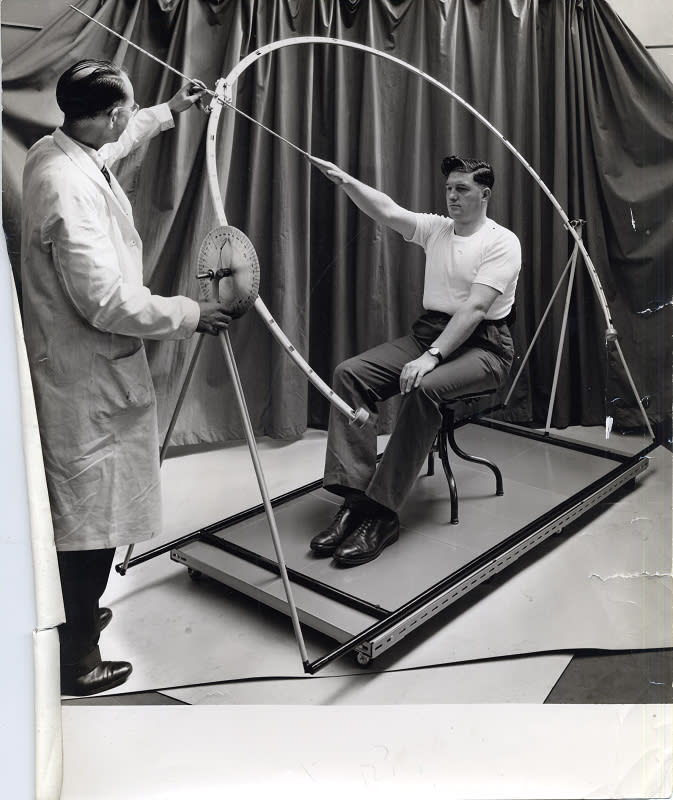

Full pressure suits are large and bulky. As a consequence, they have a major impact on the pilot's reach and flexibility. To tackle this problem, Frankenstein & Sons developed a measuring device with a circular track that extended above the wearer's head. It allowed the company to take precise measurements and make granular adjustments that maximized the wearer's reach inside high-altitude aircraft like the Avro Vulcan.

"[Otherwise] the flight engineer sits on the Vulcan, and then you find out that when he puts on a suit he can't reach the bloody knobs," Cliff Butterworth, a former Frankenstein & Sons employee told the Science and Industry Museum in 2007. "If he has to turn to keep the aircraft flying... it gets a bit serious."

NASA, meanwhile, was said to be having problems. The suits it had developed were so restrictive that astronauts couldn't raise their arms above shoulder level. "Whereas [with] the suit that was developed at Newton Heath," Fred Evans, another former Frankenstein & Sons employee explained, "the wearer of the suit could scratch the back of his neck."

Frankenstein & Sons sold one of its measuring devices to NASA for "a very nice profit," according to Butterworth. Staff interviewed in 2007 say that Ian Wright, an engineer at the company, was also invited to spend a couple of months helping NASA solve some of its mobility problems.

Frankenstein & Sons sold one of its measuring devices to NASA for "a very nice profit."

Wright clearly loved space. Documents owned by the Science and Industry Museum list him as an attendee for a 'Commonwealth Spaceflight Symposium' at the British Interplanetary Society in August 1959. He also held a talk at the Clothing Institute, which involved modelling various Frankenstein equipment, in 1960. "To the conventional tailors present at the meeting, these suits and numerous other garments were like something out of this world," a report explained. Newspaper articles also show that he appeared on the TV game show What's my Line wearing a full pressure suit.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the UK continued to test a number of full pressure suits including the Type 51 developed by Frankenstein & Sons. None of the prototypes were given the go-ahead for frontline use, however.

Then, in 1959, British physician and RAF squadron leader John Billingham started developing a suit concept that used liquid, rather than air, to regulate temperature.

While he stewed on the idea, NASA continued to pursue spaceflight. In July 1961, Gus Grissom became the second American to travel in space, after fellow Mercury Seven astronaut Alan Shepard. His capsule, nicknamed the Liberty Bell 7, landed in the Atlantic Ocean and opened its hatch cover by mistake. "He panicked and jumped out," Butterworth said in 2007. "And the water went into his neck. Fortunately for him, they had these (Navy) Seal people 'round."

According to Butterworth, NASA asked the UK's Ministry of Defence for help, who explained that it was using sealed 'neck suits.' "So they came to us and bought 12 neck suits," Butterworth told the Science and Industry Museum.

According to Frankenstein employees, at least three suits were sent to NASA over the years.

By 1962, Frankenstein had developed a survival-focused pressure jerkin that, when combined with a partial-pressure helmet and anti-g suit, could keep aircrew alive for up to one minute at 70,000 feet, followed by a rapid descent to 40,000 feet. At the same time, the first liquid-cooled prototype was being developed at Farnborough. It's not clear if this version was developed by Frankenstein & Sons. Records show that NASA did buy a full pressure suit from the company for $7,150 (or roughly $60,500, adjusted for inflation) in March 1962, however. According to Frankenstein employees, at least three suits were sent to NASA over the years.

Regardless, Billingham was hired the following year to lead NASA's environmental physiology branch at the Johnson Space Center. In the mid-1960s, he helped finesse the liquid-cooling system that eventually wound up in the Apollo 11 spacesuit.

Frankenstein, meanwhile, was hired to produce liquid-cooled suits for the RAF in 1965. These were meant for low-level flights in hot climates, however, rather than spaceflight. Early trials conducted by pilots in Libya were unsuccessful, however, and the ensuing report effectively delayed the project until 1972.

No matter. In the mid-to-late 1960s, Frankenstein had other projects in the pipeline, including a possible movie spacesuit. Frederick I. Ordway, a scientific advisor for 2001: A Space Odyssey, wrote in a retrospective: "We had our space helmets built, from our designs, at the MV Aviation Co., Ltd of Maidenhead; our spacesuits at the Air Sea Rescue Division, Victoria Rubber Works of the Frankenstein Group, Ltd. of Manchester; and our space pod interiors — instrumentation, controls, displays, etc. — at Hawker Siddley Dynamics at Stevenage not far from our Borehamwood location."

The company's involvement has never been confirmed or mentioned beyond this passage, however.

Stanley Kubrick's movie was released in 1968. One year later, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made history by wandering across the Moon together.

It's impossible to say how heavily Frankenstein's work influenced NASA's spacesuit designs. In 2007 and 2010, the Museum of Science and Industry was given numerous boxes filled with material about Wright and Frankenstein & Sons. The material inside, though, is difficult to parse without an employee's assistance. It's quite possible that some of the photos and documents will never be truly understood. What has been uncovered, however, suggests that the Manchester company had some impact on the first Moon landing. Frankenstein & Sons never went to space, but there's a good chance its aviation and survival research did.

Apollo 11 anniversary at Engadget