Indie history: How shareware helped build Epic Games

Apogee, GodGames, id and Epic laid the foundation for modern publishing.

Publishing deals in the video game industry are generally kept secret, with terms hidden behind non-disclosure agreements and the threat of legal fallout. However, in the realm of AAA publishing, it’s common for independent developers to sign contracts granting them less than 10 percent of a game’s lifetime revenue, in exchange for marketing and financial assistance from a multibillion-dollar organization. In some cases, the developer also signs away their intellectual property rights, losing creative control over the game entirely. Or, a huge company will simply buy the smaller studio outright, devouring its existing library and creative talent, and overseeing all of its future products.

In late March, Epic Games launched a multiplatform publishing initiative touting “the most developer-friendly terms in the industry.” Under this deal, developers are guaranteed 50 percent of a game’s revenue once production costs are recouped, and they retain full creative control over their own titles. Epic also promises to cover up to 100 percent of a game’s development costs, including salaries, advertising and publishing fees.

“We’re building the publishing model we always wanted for ourselves,” said Epic founder and CEO Tim Sweeney.

He’s not exaggerating. Epic Games has been experimenting with publishing models since the early ’90s, decades before the launch of Fortnite, The Epic Games Store or the Unreal Engine. We’re talking about the days of BBS, back when Sweeney was building ZZT out of his parents’ house and the World Wide Web was just flickering to life.

He’s also not alone. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, a handful of software developers suddenly found themselves on the frontlines of a new industry -- video game publishing -- as demand for their homegrown digital experiences began to boom. Developers and deal-makers like Scott Miller, James Schmalz, Jay Wilbur, Mike Wilson, Mark Rein and Sweeney built impromptu publishing systems that prioritized art over profit, collaborating and competing with massive companies like Microsoft, Sony, Electronic Arts and Take-Two in the process.

These creator-first systems are still in place today, under names like Devolver Digital, 3D Realms, Indie Fund, Raw Fury and, of course, Epic Games. Sweeney’s company isn’t the only name on the list, but with a culture-defining franchise, a popular game engine and a $15 billion valuation, it’s definitely making the most noise right now.

“When they popped up and said, ‘We're redefining the publishing deal,’ it made me chuckle,” said Devolver Digital founder Mike Wilson. “But it was also cool because it was Epic saying it. Not that it was really the same people that were involved back then, but it was like, well that's kind of cool. They were one of us, you know?”

If you don’t know, keep reading.

’90s kids

It all starts with Apogee.

“In Dallas, Apogee's like the root of the tree,” Scott Miller, the founder of Apogee and 3D Realms, said. “Pretty much everything else that happened, id Software and Hipnotic and so on, Ion Storm -- they all started with people who were once connected with Apogee, who were originally brought here to work with us in some way or another.”

Miller launched Apogee in 1987 as a way to publicize the ASCII-based games he was building out of his childhood home in Texas. At the time, burgeoning developers congregated on pre-internet bulletin board systems like CompuServe, GEnie and Prodigy, trading programming tricks and sharing their work. They employed an early version of the “free to play” model, known at the time as “shareware.” Initially, developers would publish their games, usually in full, and ask for donations from other BBS users.

Miller, approaching his mid-twenties and obsessively building video games in his spare time, designed two text adventures and attempted to have them published by Infocom, a prominent producer of interactive fiction at the time. Infocom rejected both games.

“It was like, ‘What do I do? I guess I'll just throw these online because I don't want them just to rot on my computer drive,’” Miller said.

He set them loose on the BBS community. Other developers enjoyed them, but the games ended up netting Miller less than $10,000 combined. The donation model clearly wasn’t sustainable as a full-time gig.

And then he made Kingdom of Kroz. It was an ASCII-based adventure game with 60 levels, much larger than his previous efforts. Miller changed tactics -- he broke the game into three chunks that he called “episodes,” and released just the first one on the boards. The other two episodes would be available to purchase only.

It was 1987, and Kingdom of Kroz was the first game published under the Apogee banner.

“We were using all these platforms to freely distribute our games and people were downloading them by the hundreds of thousands, in some cases by the millions,” Miller said. “And some small percentage of these people -- we estimated 1 to 2 percent, there was really no way to track -- would finish the game and think, ‘Wow, I really like this, I want more of this,’ and here's the big splash screen telling the person exactly how to order it.”

It’s a familiar system nowadays, but 33 years ago, the idea of episodic releases and free game demos was fresh. And it worked, even without the conveniences of online banking.

“At first they would just send my company a check, which is a pretty high hurdle,” Miller said. “But it worked out well enough to where we were making a lot of money that way. And eventually we added an 800-number, which was standard for the day. People would call in, make the order, give us their credit card, and we shipped the game.”

"We were making a lot of money that way."

Miller brought in about $1,000 a week with this. When he released another Kroz trilogy in 1990, he made about $2,000 a week.

“When I realized I was on to something with this pre-internet online marketing, I realized that as just myself, I couldn't make games fast enough to capitalize on this,” Miller said. “So it was back in 1990 that I quit my job and I started to basically search for other game developers that were out there who I could fund their projects and have them release their games through Apogee.”

He recruited a handful of now-legendary names and games, including John Romero, Adrian Carmack, Tom Hall and John Carmack, a group of Softdisk developers that would go on to form id Software. Apogee published their first game under the id banner, Commander Keen, in December 1990.

“It's funny, though, that the people who were most opposed to this idea were the guys that eventually became id Software,” Miller said. “John Carmack and John Romero and Tom Hall, they were completely in disbelief that this whole shareware thing could work. So I had to promise them -- I had to pay a bunch of money upfront to get their first game, Commander Keen, and I had to promise them some guarantees.”

Hall, Romero and the Carmacks developed Commander Keen in Invasion of the Vorticons in ten weeks. In its first month under the Apogee publishing model, the game brought in $20,000.

“We're just a bunch of starving kids working from home, basically,” Miller said. “That's when they realized, ‘Oh my god. We need to get out of our current jobs.’ They were working at Softdisk, which was one of these monthly disk magazines that were quite popular at the time. They pretty much immediately decided they needed to quit there and start their own little studio. And that's when they started to really roll.”

After producing a number of games for Softdisk, the next Apogee project from id was Wolfenstein 3D, an iconic game that kickstarted the contemporary, ultra-violent first-person-shooter genre. Wolfenstein 3D generated about $200,000 a month for more than a year straight.

By 1992, Miller found himself in charge of a booming independent publishing company. He’d brought his friend and fellow developer George Broussard on board, and they had a small team of employees to answer the phones and take game orders. Apogee -- and its successor, 3D Realms -- ended up producing the Duke Nukem series (managed by Broussard), Death Rally, Shadow Warrior, the original two Max Payne games, Prey and dozens of other titles.

Infocom, the publisher that rejected Miller’s first two games, was acquired by Activision in 1986 and shut down in 1989.

Aside from offering artists financial, marketing and sales assistance, Miller ran Apogee and 3D Realms with a simple premise: developers own their work. In the early ’90s, massive publishers like Activision and Electronic Arts were also signing independent teams, but it was common for these companies to take control of a developer’s intellectual property rights as part of the publishing contract. Signing with a major publisher brought plenty of stability to a project, but developers often lost control of their own creation in the process. This still happens today.

“I never tried to take anyone's IP,” Miller said. “Like for id Software I said, ‘You get to own Wolfenstein. That's still yours. We're just basically publishing it, and marketing it, and doing all that kind of stuff.’ Whereas it was very often throughout the ’90s, and way more often even now, that the publisher would say, ‘Well, if we're going to fund this project and publish it, we want the IP rights too.’ It's very dangerous for a developer because at some point, they can lose the right to continue to make the game, and that kind of cuts them out of the picture for future revenues from that IP.”

That’s one reason id Software was able to establish itself as a gaming powerhouse in the early 1990s. The id boys saw how large the market for their games was, so they took their IPs and published them in-house, shareware-style, and only partnered with publishers for the full retail launch. Once the cultural cachet of series like Doom and Quake became clear, id was able to negotiate better deals with large publishers like Activision.

While Miller was building up Apogee in Texas, a young Tim Sweeney was selling his first game, ZZT, to BBS users out of his parents’ house in Maryland. His father fulfilled every order himself until shipping the last copy of ZZT in 2013.

“Digital storefronts are a $100 billion-a-year business across all platforms now,” Sweeney said in 2019. (Epic Games declined an interview request for this particular story.) “With ZZT, at some point after I released it, I was making $100 a day. I was like, ‘Oh, my god. I'm rich. I can make a living off of this.’”

Sweeney saw what Apogee and id Software were doing, and wanted to try it out himself. He founded Epic MegaGames in early 1992.

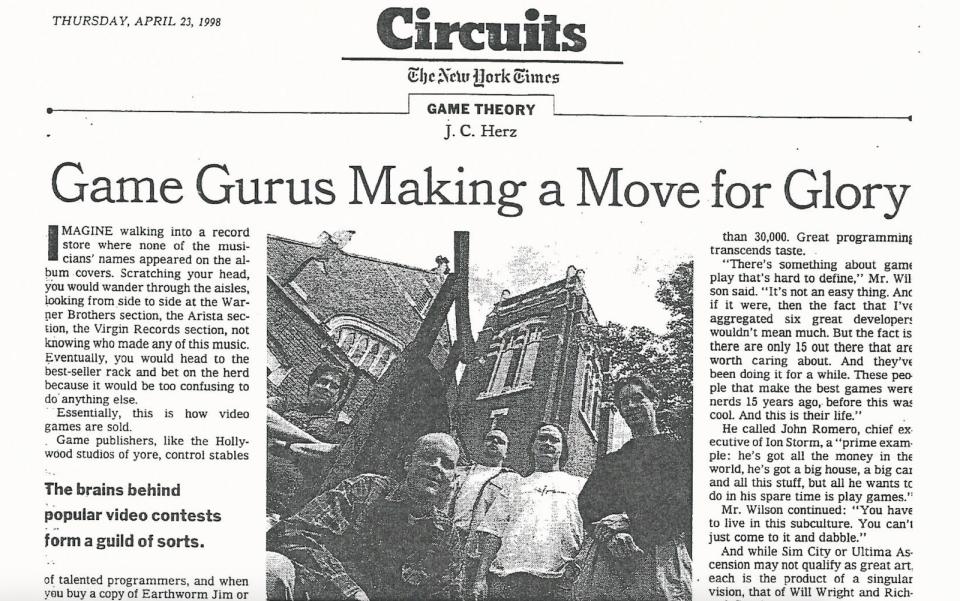

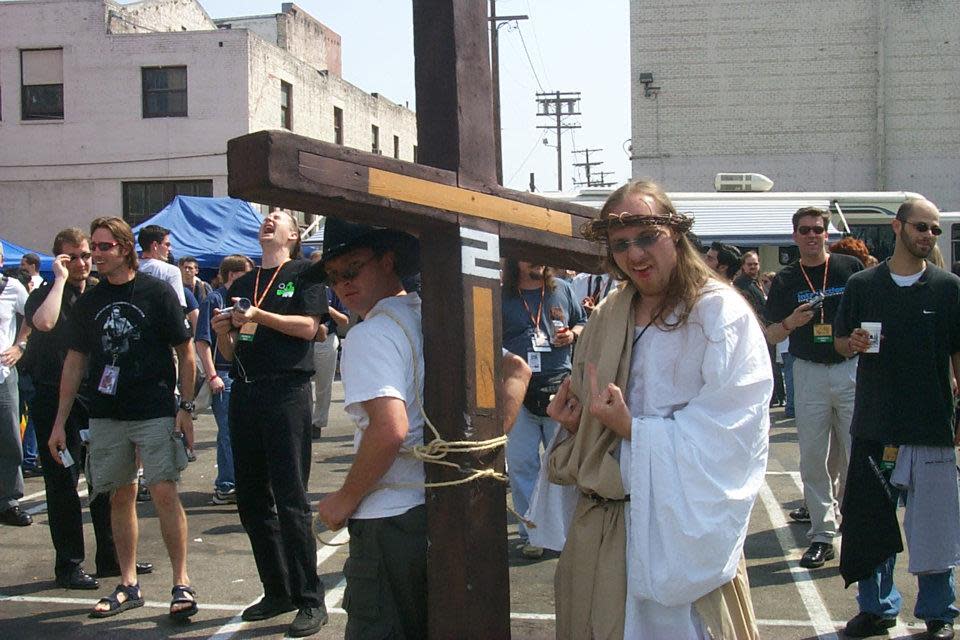

All of these companies, people and grand ideas about artist-first publishing converged in a single place in 1998: Gathering of Developers, or GodGames.

Y2K

It feels like Mike Wilson has his hands in every part of this story, or at least a pinky finger. Today, he’s the co-founder of Devolver Digital, one of the most prominent indie-game publishing houses around, but in the mid ‘90s he was handling PR and marketing for his buddy’s new business, id Software.

“I got into the industry because one of my best friends in high school and college, he was just a pen and paper artist,” Wilson said. “Adrian Carmack ended up being the guy that drew all these wonderful Nazis and demons for us back in the day. But he barely was a computer guy. He learned [Deluxe Paint] so that he could make those games. And so for me, it was very obvious to see that these guys were artists.”

Wilson joined id in 1996 and worked alongside Jay Wilbur on the studio’s business dealings. Wilson helped with self-publishing efforts and managed partnerships with big companies like GT Interactive and Activision for games in the Doom and Quake series. He remembers wild amounts of money flying around the video game industry at the time, though most of it was concentrated in the vaults of a few AAA businesses. The tech sector was growing rapidly -- remember, the dot-com bubble didn’t burst until 2002 -- and fresh-faced developers were signing bad deals left, right and center, according to Wilson.

Take GT Interactive, the company that published Doom II, for example.

“They were just some old dudes from the music industry, and so they came over with the same tricks from the music industry,” Wilson said. “Where it’s, ‘We're the people with the money, we control distribution, the artists are whatever.’ They really looked at game developers as toy makers, more so than artists. Just like work-for-hire programmers.”

In short, many publishers were screwing over independent developers as a manner of business. Wilson accused these companies of misrepresenting the publishing process in order to hide money from developers, or simply lying outright about sales numbers and fees.

GT Interactive distributed the retail version of Quake, and id was making no more than $9 a box, when PC games at the time were selling for $40.

“The last thing I did for id was re-negotiate their deal, based on our soft publishing success of Quake shareware,” Wilson said. “I got them from seven bucks a box to 18 bucks a box, and it just demonstrated how much room there really was, and how full of shit these companies were that were telling the developers that these were really good deals back then.”

John Romero left id Software in 1996 and formed Ion Storm with Tom Hall; Wilson joined six months later as CEO. Wilbur, id’s main deal-maker, took a job at Epic around this same time, and he’s still there today as VP of business development.

Wilson helped grow Ion Storm in its first year, and brought aboard Warren Spector, who would create Ion Storm’s only big hit, Deus Ex, in 2000. The studio folded in 2005.

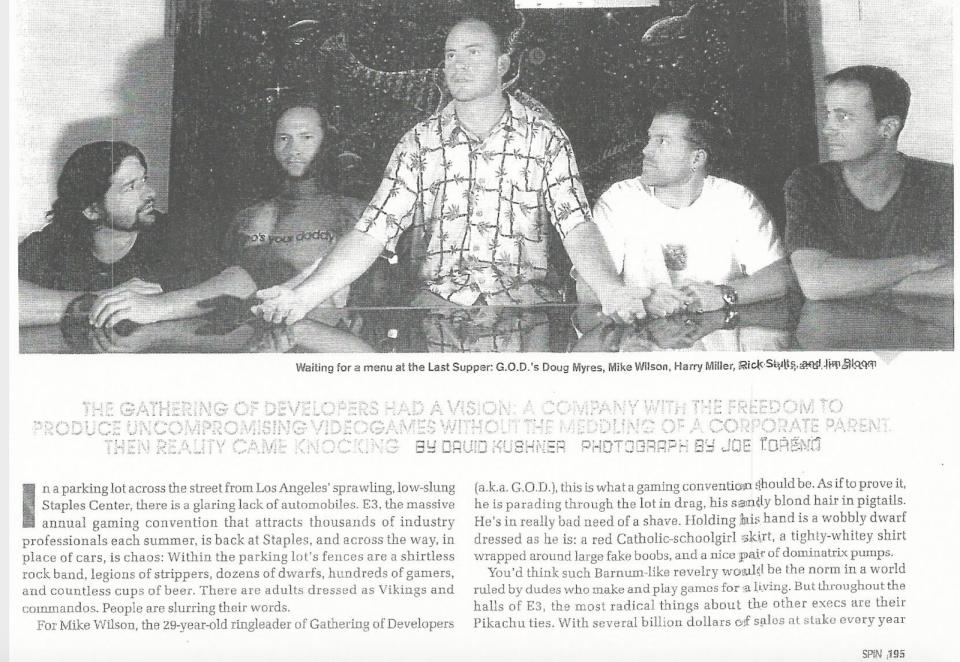

By then, Wilson was long gone from Ion Storm. In December 1997, he broke away from the company and just a month later, he’d started Gathering of Developers with Harry Miller, Jim Bloom, Rick Stults and Doug Myres.

The mission of Gathering of Developers, or GodGames, was to establish a publishing system that gave artists more control over and information about their deals. Six studios signed on to GodGames at launch: Terminal Reality, Edge of Reality, PopTop Software, Ritual Entertainment, 3D Realms (formerly Apogee) and Epic Games.

Here’s where our storylines converge. Miller, as the head of 3D Realms and an accidental Texas businessman himself, understood Wilson’s goal with GodGames. Miller wrote up a document called The Ten Developer Commandments and they threw it online; it contained tips and truths for developers navigating the publishing process, argued for higher royalty rates, and laid out the importance of maintaining IP ownership. Here’s how it began:

Presented here for all developers of the world, courtesy of Gathering of Developers, are guidelines and inside information that may otherwise take you years to learn, and many regrets along the way. Make no mistake, this is inside information your publisher doesn't want you to know. With this knowledge you'll be able to negotiate far better publishing agreements that give your company significantly improved revenues, power and value.

Our hope here at the Gathering is to raise the bar for all developers in our industry, not just those signed with us. Without further ado, we bring you two tablets of great knowledge and wealth...

The Ten Developer Commandments provided actual numbers and examples of “fair” deals, including a $750,000 baseline marketing budget for each game, and advances of $2 million as standard practice. Royalties were set up on an escalating scale in favor of the developer, starting at 15 percent for unproven studios and rising to 50 percent as the sales rolled in.

“To this day now, any time I've ever done an agreement with a publisher, I've made sure it's a similar sort of pattern, an escalating royalty,” Miller said. “Because an extreme example is, hey, once this game's made back its initial advances times 10, why not have the royalty go up 10 more points in the developer's favor? Everyone's rolling in the cash by that point.”

GodGames was prolific in its first two years, publishing titles including Jazz Jackrabbit 2, Railroad Tycoon 2 and Age of Wonders.

“We somehow managed, with a bunch of people that had never been in the industry, to green-light and produce and publish 8 million units selling new IPs in two and a half years,” Wilson said. “It was working.”

And other, larger companies were taking notice. In June 1998, Gathering of Developers signed a distribution contract with Take-Two Interactive, one of the fastest-growing businesses in video games at the time. Take-Two was founded in 1993 by Ryan Brant, the son of Peter Brant, who ran Interview magazine alongside Andy Warhol. The younger Brant raised $1.5 million from family and private investors to start Take-Two, and in less than four years, the company was worth tens of millions. Its initial strategy was to hire well-known actors to star in full-motion video games, working with folks like Christopher Walken, Dennis Hopper and Karen Allen. Take-Two was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in April 1997, and afterward, it began an acquisition spree.

When Gathering of Developers and Take-Two signed their distribution contract in 1998, Wilson was 28 and Brant was 27.

“He was a fucking genius, like he was the smartest guy in any room,” Wilson said. Unfortunately, he added, Brant was also a liar.

“They controlled our only cash flow because they had our distribution rights,” Wilson said. “And so they would get the money from retail and from the distributors, and then they would give us reports and send us money. Anyway, basically they just kept us barefoot and pregnant, always on the verge of going out of business. And meanwhile, it turns out our games are all selling way better and there was plenty of money to keep us in business.”

"Basically they just kept us barefoot and pregnant."

Wilson is confident in this assessment because he ended up working for Take-Two. Twice.

While Gathering of Developers was bleeding cash and attempting to support a roster of talented developers, Take-Two was buying companies like BMG Interactive, which had just launched Grand Theft Auto in Europe. Take-Two brought the title to North America, established an in-house label named Rockstar Games, and secured its place among the largest video game businesses in existence. Take-Two continued acquiring companies, and in 2000, it bought Gathering of Developers outright.

“We sold the company with a gun to our heads, not wanting to sell it at all,” Wilson said. “And we had to wait out a year to get our stock and leave, and we were all pretty heartbroken.”

After a depressing stint under Take-Two, Wilson and his core team left and started a short-lived video magazine called SustanceTV. It shut down in a year, and Wilson found himself back at Take-Two, in charge of the company’s PC division.

“In the interim, they had shipped Grand Theft Auto III and become this giant company,” Wilson said. “No one was really watching the Gathering of Developers stuff. And meanwhile all of our games had gone on to become this $400 million business. And so when they hired me back, that's when I discovered how well we had actually done in all the games we had published. Even the ones that we thought were the biggest losers, every single one had made money.”

In attempting to establish a no-bullshit, equitable and artist-oriented publishing model, Wilson had fallen victim to the same shady business practices he was trying to destroy.

SPIN magazine covered the dissolution of GodGames in its December 2000 issue, and one quote from that story seems to capture the sentiment of AAA publishers at the time. It comes from Michael Pole, who was then EVP of Activision Worldwide Studios, and it goes like this:

“They mortgaged their future trying to sign up the best and brightest. What happens when you mortgage your future is that you're eventually going to have to show a profit. We're in the business of making money. Making games is icing on the cake.”

Present

May 4th marked the 20th anniversary of GodGames’ acquisition by Take-Two. Wilson, Miller and Sweeney have all trod their own paths in the video game industry, and they’re all still active today. They started out in the undefined, pre-internet, post-shareware fog of the early 1990s, where they learned plenty about large-scale business and protecting artist integrity. They share a common foundation.

Wilson is now a founding partner of Devolver Digital, the company he launched in 2009 with Harry Miller, Rick Stults, Nigel Lowrie and Graeme Struthers.

“We learned that staying small was good, so all of that just also coincided with this new wave of these tiny teams that started appearing around the time we started Devolver,” Wilson said. “And the difference is, these teams did not aspire to build empires. They were not making small games so that they could make big ones later. They seemed to just inherently know that smaller meant, A, more money to go around without something that needed to be mainstream, and B, freedom.”

"We learned that staying small was good."

Devolver offered -- and still offers -- easy-to-understand contracts, no IP ownership clauses, and royalty rates that start at 50 percent (just like Epic’s new deal). It feels like Wilson has found the sweet spot where his publishing ideals can thrive, and he’s aiming to keep Devolver sustainable, agile and independent. The studio found its footing with Serious Sam, a franchise created by Croteam, one of the studios GodGames published back in the day. Serious Sam HD: The First Encounter launched in 2009 under Devolver, followed by a sequel in 2010. Serious Sam 4 is due to hit PC and Google Stadia in August.

“Gathering's way of doing business is what enabled Devolver to come into existence in the first place,” Wilson said. “Croteam owned the Serious Sam IP and could work with whomever they wanted, and were financially independent, because the original Serious Sam game was signed with Gathering. For the first two years of our existence, Serious Sam was all we had, and that series along with The Talos Principle, also from Croteam, continue to be a very significant chunk of our overall sales, and doing the Serious Sam indie series was what set us on our path of working with this new wave of tiny indies.”

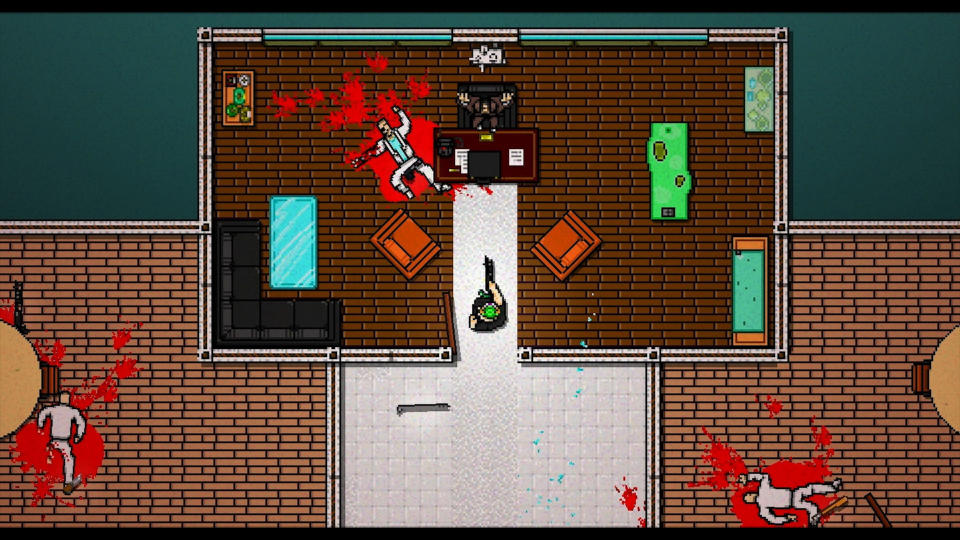

Devolver’s big break came in 2012 with the release of a blood-soaked, top-down, neon-lit action title named Hotline Miami. The studio has since published nearly 100 titles, including mainstream hits like Gris, Hatoful Boyfriend, The Red Strings Club, Reigns, Ruiner, Metal Wolf Chaos XD, and of course, Hotline Miami 2.

“When the Hotline Miami guys found such success, they didn't go hire 10 or 20 people,” Wilson said. “They've been slaving away on their next project, just the two of them, just like they did before.”

Miller’s 3D Realms ended up in a legal battle with Take-Two over the Duke Nukem franchise, and eventually the rights to the series were transferred to Gearbox Software. SDN Invest acquired 3D Realms in 2014, and today, Miller serves as an adviser to the studio.

“We've always done 50-50 deals at 3D Realms,” Miller said. “But Epic, of course, is way, way, way, way, way, way bigger. And for them to do this, it's much more of a seismic wake-up call for the industry.”

Under Epic, Sweeney launched the Unreal series, Unreal Engine, a lineup of Unreal Tournament games and the Gears of War franchise. Tencent, the Chinese technology giant, acquired 40 percent of Epic Games in 2012 as the company eyed an expansion into living, online games. The company remained private and under Sweeney’s control.

Just before the acquisition, Epic revealed Fortnite, a cooperative survival shooter with base-building, hordes of zombies and cartoonish graphics. The game launched in 2017 and flopped -- until Epic released a new mode, Fortnite Battle Royale, and the gaming landscape was forever changed. Today, Epic’s value hovers around $15 billion.

This puts Epic in the same arena as giants like Activision, EA, Take-Two, Valve, Sony and Microsoft. All of these companies act as publishers, and most of them have toyed around with indie-publishing schemes. Microsoft has ID@Xbox, EA has its Originals line, and in the early days of the PlayStation 4, Sony was the undisputed king of securing high-profile indies. That’s since changed as the market has evolved and companies with a sole focus on indie publishing have stepped up, including Devolver, Annapurna Interactive and Raw Fury.

Exclusivity deals drive the top tiers of the industry, with companies like Microsoft, Sony and now even Google vying for players’ attention. Snagging exclusive rights to a hot new game is the best way to ensure players will show up in a specific company’s ecosystem, and the easiest way to score an exclusive game is to simply buy the studio that’s making it. This means acquisitions are the norm for the largest businesses. Xbox Game Studios, for instance, has 15 organizations under its umbrella, including Double Fine, Playground Games, Obsidian Entertainment, Ninja Theory and Mojang, the home of Minecraft.

Epic is playing this game, too, and its main competitor is Valve, another multibillion-dollar powerhouse. The Epic Games Store launched in 2018, offering the first real competitor to Valve’s Steam in a decade. It secured a handful of exclusive and timed-exclusive titles right away, keeping those games off of Steam.

Epic is playing this game, too.

Meanwhile, in mid-2018, Valve acquired Firewatch studio Campo Santo and In the Valley of Gods, its high-profile in-progress game. Work on that title has been effectively shut down as the Campo Santo team works on other Valve projects, like Half-Life: Alyx.

As a rule, the Epic Games Store takes 12 percent of a game’s sales revenue, significantly less than Steam’s 30 percent standard. Sweeney has been vocal about pushing Steam to offer better deals to developers, though Valve hasn’t budged. Valve founder Gabe Newell has kept himself out of the conversation entirely.

“I used to have a higher opinion of Gabe,” Miller said. “But the fact that he's not adjusting the rates in favor of developers is disappointing because he's got a developer background too. And Valve is a development company. Why isn't he more pro-developer in the position he's at and at least cut it down to 20 percent?”

If Steam committed to a permanent 88% revenue share for all developers and publishers without major strings attached, Epic would hastily organize a retreat from exclusives (while honoring our partner commitments) and consider putting our own games on Steam.

— Tim Sweeney (@TimSweeneyEpic) April 25, 2019

Epic Games Publishing offers 50-50 profit sharing, no IP transfers and full funding for projects. Three studios have signed on so far: Remedy Entertainment (Control, Alan Wake), Playdead (Inside, Limbo) and genDESIGN (The Last Guardian). This developer-focused, acquisition-averse system may ring true to people like Sweeney, Wilson and Miller, but it’s still a strange move for such a huge video game organization.

There are hundreds of other characters in this story. The contemporary publishing scene formed over decades of deals, successes and disappointments, and at the highest levels, it has led to a predictable cycle of mass lay-offs and soul-crushing crunch. If the people at the top of the industry are at all interested in fostering innovation, health and sustainability — and, yes, profit — an artist-first publishing approach makes more sense.

“I don't know what AAA studios are paying indies these days, but the answer is usually as little as possible,” Wilson said. “That's why you see all these big companies with these big franchises and the same cycle of layoffs and all of that, because they're just doing the math. It's not really about the people at that point.”

Forget artist-first. People-first is a fine starting point.

Update (6/16 3PM ET): This article was updated post-publication to clarify the internal structures and business models of id Software and Ion Storm, after receiving additional information from John Romero about the early days of those companies.