atomicclock

Latest

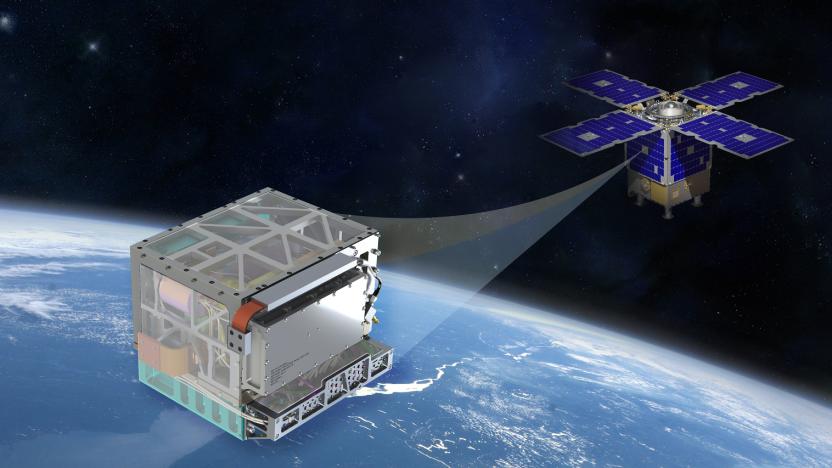

NASA will test a key deep space navigation tool this year

The Deep Space Atomic Clock (DSAC) is finally ready for testing, and NASA's JPL has begun preparing it for launch this year after working on it for two decades. Current space vehicles and observatories already use atomic clocks for navigation -- they are, after all, some of the most accurate timekeeping devices ever. However, the way they work isn't ideal for use in vessels going beyond Low-Earth Orbit.

Researchers have increased atomic clock precision yet again

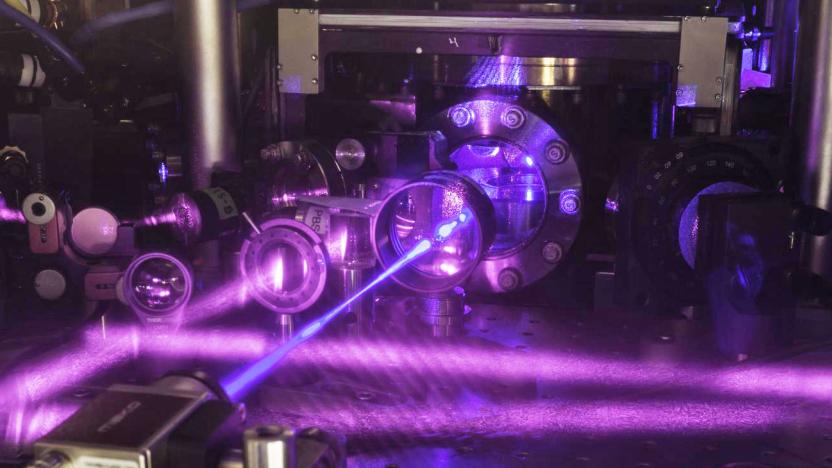

Researchers have pushed the precision and stability of atomic clocks to increasingly greater levels over the last few years. A big advancement was the introduction of optical lattices, lasers which essentially quarantine individual atoms and boost accuracy by keeping them from moving around and interacting with each other. Scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have used this method to develop clocks so stable, they can keep extremely precise time for thousands and even billions of years. The team's most precise clock was created in 2015, but research published this week in Science describes a new version that just took that top spot.

World's most precise atomic clock will still be spot-on in 5 billion years

Most of us only pay attention to time when it's causing headaches, but the same can't be said of a team of researchers working out of the University of Colorado at Boulder. Led by National Institute of Standards and Technology fellow Jun Ye, they've crafted an atomic clock that can keep precise time for billions of years, a world record. This hefty new timekeeper can tick off the seconds with the same unflinching regularity as the best of them, but it'll be about 5 billion years before it experiences its first temporal hiccup. For the morbidly curious, that means the clock will still be precise when the sun starts ballooning into a massive red giant. That may not sound like a huge deal now, but when our descendants start laying in escape routes to some more pleasant planets they'll be glad for that extra precision. How does the thing work? Well, strontium atoms are held in "traps" formed by lasers, and researchers are able to track how often they oscillate by using that laser light to get them moving. It's hardly a new technique, but you can't argue with the results: The new clock is 50 percent more precise than the last record-setter, and Ye says that there are plenty more breakthroughs to come.

Scientists set new stability record with ytterbium atomic clock

The story of scientific advancement is rarely one of leaps and bounds. More often than not it's evolution over revolution, and the story of the so-called ytterbium atomic clock fits that bill perfectly. You may remember that in July researchers improved upon the standard, cesium-powered atomic clock model by using a network of lasers to trap and excite strontium; instead of losing a second every few years, the Optical Lattice Clock only lost a second every three centuries. Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology made a pretty simple tweak to that model: replace the strontium with ytterbium and, voilà, another ten-fold increase in stability. Ten thousand of the rare-earth atoms are held in place, cooled to 10 microKelvin (just a few millionths of a degree above absolute zero) and excited by a laser "tick" 518 trillion times per second. Whereas the average cesium atomic clock must run for roughly five days to achieve its comparatively paltry level of consistency, the ytterbium clock reaches peak stability in just a single second. That stability doesn't necessarily translate into accuracy, but chances are good that it will. That could could mean more accurate measurements of how gravity effects time and lead to improvements in accuracy for GPS or its future equivalents. The next steps are pretty clear, though hardly simple: to see how much farther the accuracy and stability can be pushed, then shrink the clock down to a size that could fit on a satellite or space ship. The one currently in use at the NIST is roughly the size of a large dining room table.

Laser-powered atomic clock fuels temporal pedants' ire

If you thought that your regular atomic clock, which loses a second once every few years, is adequate for your needs, then Dr. Jerome Lodewyck wants a word. His team at the Paris Observatory claims to have invented an atomic clock which only loses a second every three centuries. Rather than measuring the oscillations of caesium atoms, the "Optical Lattice Clock" uses a laser to excite strontium atoms which vibrate much faster and are, therefore, more accurate. Of course, it's a cruel irony that just as soon as someone's plonked down $78,000 on a Hoptroff No. 10, a rogue gang of scientists find a way to make it obsolete.

Physicists construct the most accurate clock the world has ever seen

Calling a clock the most accurate ever may sound like hyperbole, but physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado have built a pair of devices that can claim that title. The team used an optical lattice to address an issue that plagues atomic clockmakers: constantly shifting frequencies that negatively impact the accuracy of their measurements. For example, a single second can be defined by the frequency of light emitted by an atom when electrons jump from one state to the next, but those frequencies change as the atom moves. The optical lattice essentially suspends atoms to minimize the Doppler effect produced by that movement. By combining the lattice with the element ytterbium, the group was able to create a device that measures time with a precision of one part in 1018. To put that into perspective, Andrew Ludlow, one of the paper's authors, said, "A measurement at the 1018 fractional level is equivalent to specifying the age of the known universe to a precision of less than one second." To read more about the team's work, you can find the full PDF at the source.

New single ion clock is '100 times more precise' than existing atomic models

Researchers at the University of New South Wales have developed a new type of atomic clock that measures an atom's neutron orbit instead of the electron's flight path. This method is apparently accurate to 19 decimal places, with several lasers shifting electrons in a certain way, allowing Professor Victor Flambaum to measure the "pendulum" motion of the neutron. It's purportedly close to 100 times more precise than its predecessors -- all with no freezing involved. These existing atomic clocks may be accurate beyond 100 million years, but for this new breed of hyper-accurate timekeeping, you'll only need to reset the clock once every 14 billion years. And we have no idea how they calculated that.

Seiko's 'active matrix' E Ink watch will be on sale by end of 2010

It's always good to see a concept, particularly one as appealing as Seiko's "active matrix" E Ink watch, make it to retail product. The company's had a thing for E Ink timepieces for a while now, but what sets this new one apart is the supposed 180-degree viewing angle it affords -- and, of course, those retro good looks do it no harm either. Then there's also the radio-controlled movement, which receives its time from the nearest atomic clock, and the solar cells framing that electrophoretic display. All very nice and neat, but the best news is that it might (might!) be priced within reach of regular Joes and Vlads like us. We'll know soon enough, a retail release is expected by the end of the year.

New atomic clock claims title of world's most accurate

You may have thought that the previous world's most accurate clock was good at keeping time, but it's apparently nothing compared to this new strontium atomic clock developed by scientists at the University of Colorado, which is supposedly more than twice as accurate and just as atomic. To achieve that impressive feat, the scientists made use of the same so-called "pendulum effect" of atoms as before, but took things one step further by holding the atoms in a laser beam and freezing them to almost -273 degrees Celsius, or the temperature at which all matter stops resonating. In clock terms, that translates to about one second lost every 300 million years. Of course, that's still one second too many for the researchers, and they say they "dream of getting an atomic clock with perfect precision." You just know you never want to be late for a meeting with these guys.

Gurus develop way to shrink atomic clock... with lasers

The world's most accurate clocks got even more accurate just a few years back, but now a team from the University of Nevada in Reno is looking to make the atomic clock way, way smaller. Housed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Boulder, Colorado, these so-called "fountain clocks" send out clouds of caesium atoms through a vacuum chamber in a magnetic field; from there, microwaves in the chamber excite the atoms and then emit light as they drop to a lower hyperfine state. All that rocket science aside, the real point here is that all that magic requires a chassis about the size of a modern day refrigerator. Andrei Derevianko and Kyle Beloy have conjured up the idea of "trapping atoms in place using lasers," which would obviously require far less space for the time telling to happen. Just think -- a chicken in every pot and an atomic clock on every wrist.[Image courtesy of PSU]

Oregon Scientific Crystal Weather Station brings some flair to the forecast

Oregon Scientific has been busting out some pretty slick gear lately, and its new BA900 Crystal Weather Station is no exception. The acrylic block features three laser-engraved 3-D icons that light up in color to represent sunshine, precipitation, or cloudy skies, while the radio-controlled atomic clock in the base switches to a temperature readout with just a wave of your hand. We're hearing this thing will ship in December for about $60 -- just in time for that rain icon to be rendered totally inaccurate.[Via Red Ferret]

NIST's new, even more precise atomic clock

One wouldn't think that being a second off every, oh, 70 million years or so, would be such a huge deal, right? Apparently that benchmark just isn't timely enough for the National Institute of Standards and Technology, whose Time and Frequency Division has fabricated an experimental atomic clock based on a single mercury atom in favor of the fountain of cesium atoms used now. They've discovered the prototype is even more accurate than the current standard, and would only lose one second every 400 million years. Obviously nobody reading this will even be around in 400 million years (um, right?), but there are reasons to improve aside from holding the time steady: precise time-keeping aids in accurate syncing of GPS and navigation systems, telecommunications, and deep-space networks. We admit, this whole thing leaves us a bit flabbergasted, but the sense of absurdly painstaking scientific security we'll get from knowing that while civilizations rise and empires fall, no one will live to see this atomic clock miss a beat -- well, that couldn't have come a moment too soon.