FutureInterfacesGroup

Latest

Speculative gadgets at the Future Interfaces Group

To try to get a glimpse of the everyday devices we could be using a decade from now, there are worse places to look than inside the Future Interfaces Group (FIG) lab at Carnegie Mellon University. During a recent visit to Pittsburgh by Engadget, PhD student Gierad Laput put on a smartwatch and touched a Macbook Pro, then an electric drill, then a door knob. The moment his skin pressed against each, the name of the object popped up on an adjacent computer screen. Each item had emitted a unique electromagnetic signal which flowed through Laput's body, to be picked up by the sensor on his watch.

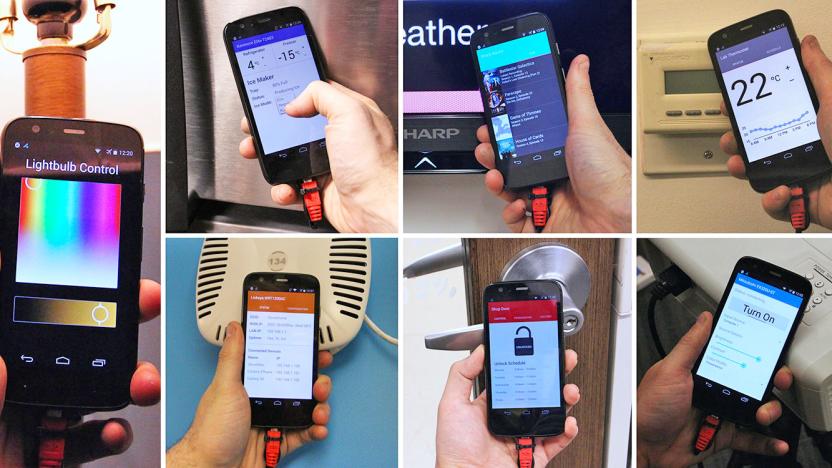

Future phones will ID devices by their electromagnetic fields

While NFC has become a standard feature on Android phones these days, it is only as convenient as it is available on the other end, not to mention the awkwardness of aligning the antennas as well. As such, Carnegie Mellon University's Future Interfaces Group is proposing a working concept that's practically the next evolution of NFC: electromagnetic emissions sensing. You see, as Disney Research already pointed out last year, each piece of electrical device has its own unique electromagnetic field, so this characteristic alone can be used as an ID so long as the device isn't truly powered off. With a little hardware and software magic, the team has come up with a prototype smartphone -- a modified Moto G from 2013 -- fitted with electromagnetic-sensing capability, so that it can recognize any electronic device by simply tapping on one.

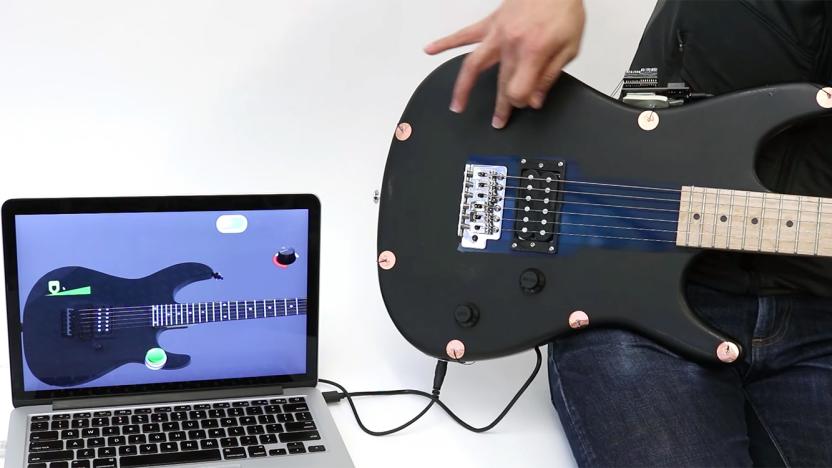

Get ready to 'spray' touch controls onto any surface

Nowadays we're accustomed to the slick glass touchscreens on our phones and tablets, but what if we could extend such luxury to other parts of our devices -- or to any surface, for that matter -- in a cheap and cheerful way? Well, apparently there's a solution on the way. At the ACM CHI conference this week, Carnegie Mellon University's Future Interfaces Group showed off its latest research project, dubbed Electrick, which enables low-cost touch sensing on pretty much any object with a conductive surface -- either it's made out of a conductive material (including plastics mixed with conductive particles) or has a conductive coating (such as a carbon conductive spray paint) applied over it. Better yet, this technique works on irregular surfaces as well.

Navigate your smartwatch by touching your skin

Smartwatches walk a fine line between functionality and fashion, but new SkinTrack technology from Carnegie Mellon University's Future Interfaces Group makes the size of the screen a moot point. The SkinTrack system consists of a ring that emits a continuous high-frequency AC signal and a sensing wristband that goes under the watch. The wristband tracks the finger wearing the ring and senses whether the digit is hovering or actually making contact with your arm or hand, turning your skin into an extension of the touchscreen.

Experimental UI equips you with a virtual tape measure and other skeuomorphs

While companies like Apple are moving away wholesale from faux real-world objects, one designer wants to take the concept to its extreme. Chris Harrison from CMU's Future Interfaces Group thinks modern, "flat" software doesn't profit from our dexterity with real-world tools like cameras, markers or erasers. To prove it, he created TouchTools, which lets you manipulate tools on the screen just as you would in real life. By touching the display with a grabbing motion, for example, a realistic-looking tape measure appears, and if you grab the "tape," you can unsheathe it like the real McCoy. He claims that provides "fast and fluid mode switching" and doesn't force designers to shoehorn awkward toolbars. So far, it's only experimental, but the idea is to eventually make software more natural to use -- 2D interfaces be damned.