timeline16genedit

Latest

First US CRISPR gene editing trial in humans seeks approval

The federal committee that monitors DNA experiments on humans will make its first judgment on a CRISPR case next week. The Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee is looking at a proposal from the University of Pennsylvania, which wants to use the gene editing technique. The plan is to harvest T-cells from cancer patients and re-program them to better fend-off cancer cells. Rather than pumping people full of debilitating drugs and hope that cancers die off, the idea is that our own immune systems can do a better job. But in order to make it work, the cells need to have certain built-in safety features shut off, hence the need for oversight.

Gene-edited organisms aren't ready for the real world

Gene editing holds the promise of eliminating diseases and perfecting humanity, but is it truly ready for real life? Not by a long shot, if you ask the National Academy of Sciences. It just issued a report warning that organisms modified with gene drives (that is, genetic additions meant to propagate through reproduction) "are not ready" to be released in the wild. We don't understand enough about how they work, the report says, whether it's their inner workings, their ethical questions or their impact on the environment.

RNA gene editing could stop viruses in their tracks

The gene editing technique CRISPR promises to treat all kinds of genetically-linked conditions, but it's so far limited to tweaking DNA, not the RNA that does everything from carrying protein sequence info to regulating gene expression. That may change soon, however. Scientists have discovered that a commonplace mouth bacterium (Leptotrichia shahii) can be programmed to break down whatever RNA you want. You could rip apart viruses, which are frequently based solely around RNA, or kill a cancer cell by denying it the chance to make vital proteins.

Scientists want to perfect humanity with synthetic DNA

Following a controversial top-secret meeting last month, a group of scientists have announced that they're working on synthesizing human genes from scratch. The project, currently titled HGP-Write, has the stated aim of reducing the cost of gene synthesis to "address a number of human health challenges." As the group explains, that includes growing replacement organs, engineering cancer resistance and building new vaccinations using human cells. But in order for all of that to happen, the scientists may have to also work on developing a blueprint for what a perfect human would look like.

New algorithm performs complex DNA origami

Researchers from MIT, Arizona State University and Baylor University have developed a new algorithm that promises to simplify the arduous and complex task of assembling DNA into structures other than a double helix. These structures could eventually be used as everything from DNA storage modules to delivery vehicles for CRISPR enzymes and other medicines, but until now the process of creating them has been prohibitive.

Gene editing discovery might treat many more diseases

In theory, gene editing could eliminate genetic diseases by correcting the flaws in your DNA. However, there's one big obstacle: the current CRISPR technique has trouble modifying individual DNA letters. As most genetic conditions revolve around mutations of those single letters, that leaves most conditions untreatable. However, Harvard researchers might have just made a breakthrough that turns gene editing into a true disease-ending weapon.

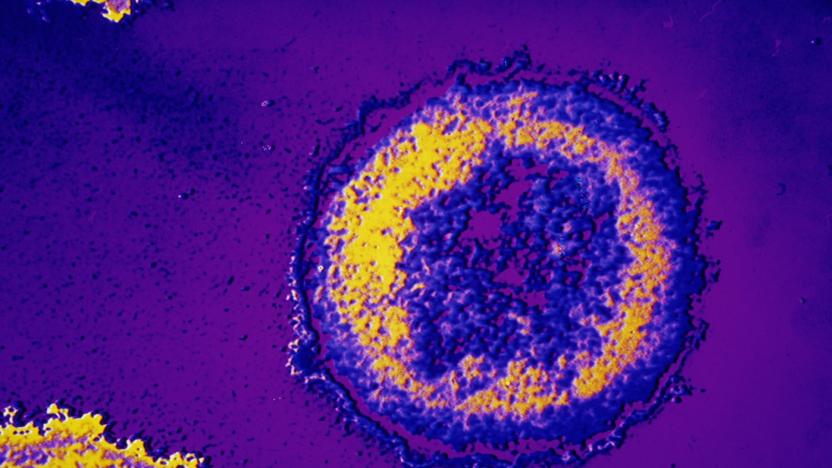

HIV resists attempts to cripple it with gene editing

It's tempting to treat gene editing as a cure-all: surely you can end diseases and viruses by changing or removing the qualities that make them dangerous, right? Well, it's not quite that simple. Researchers trying to cripple HIV by cutting up its DNA (using CRISPR) discovered that some virus samples not only survived the attack, but mutated to resist these incursions. The host T cell actually helped things along by trying to repair the cuts, inserting DNA bases and creating a mutated virus that couldn't be detected by the immune system.

Gene-modified autistic monkeys could lead to a cure for humans

There's little doubt that gene editing could be one of the greatest advances in medical science, since it might let you "turn off" conditions. However, the way you test that editing is another challenge entirely -- and some scientists in China are pushing some boundaries to make it work. They've used genetic engineering to breed over a dozen macaque monkeys with a flawed gene that triggers a rare form of autism in humans. The hope is that researchers can not only study how brains function with this condition, but experiment with treatments that could be useful on people. Ideally, the researchers will use a gene editing system like CRISPR to eliminate the condition outright.

President Obama wants US to 'reignite its spirit of innovation'

President Obama gave his final State of the Union address on Tuesday. In it, he discussed how far the country has come over the last year and where he sees it going in the future. But beyond the expected talk of a rebuilt, stronger economy, soaring high school graduation rates and new civil liberties, he laid out a bold plan to, as he puts it, make "technology work for us, and not against us."

Scientific community approves human gene editing studies

Human gene editing research is extremely controversial due to numerous ethical, moral and legal reasons that some groups would prefer to see it banned outright. Those who do want it to move forward can breathe easily for now, though, as the leaders of a summit held by the US National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the United Kingdom's Royal Society have decided to support human gene editing research. The scientists are even OK with modifying eggs, sperm and embryos (collectively called germline cells), so long as the edited cells stay in the lab and aren't used to induce pregnancies. In other words, creating designer babies is a no-no. We'll bet that means the NIH will uphold the ban on funding studies that deal with embryo engineering.

Scientists show that gene editing can 'turn off' human diseases

Gene editing has already been used to fight diseases, but there's now hope that it might eliminate the diseases altogether. Researchers have shown that it's possible to eliminate facial muscular dystrophy using a newer editing technique, CRISPR (Clusters of Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) to replace the offending gene and 'turn off' the condition. The approach sends a mix of protein and RNA to bind to a gene and give it an overhaul.

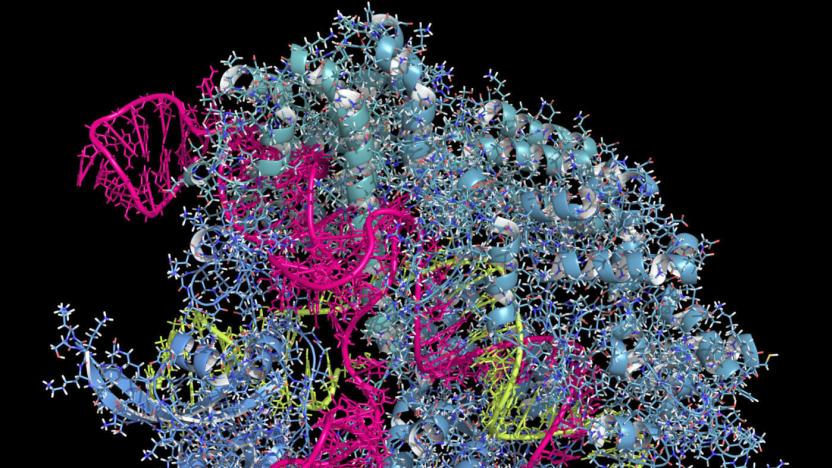

Scientists create first genetically modified human embryo

For the first time in history, a team of researchers have successfully edited the genes of a human embryo. The researchers from Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou reportedly used the CRISPR/Cas9 technique to knock a gene called HBB, which causes the fatal blood disorder β-thalassaemia, out of donor embryos. This marks the first time that the CRISPR technique has been employed on an embryonic human genome. The CRISPR/Cas9 method utilizes a complex enzyme (aka a set of "genetic scissors") to snip out and replace faulty gene segments with functional bits of DNA. The technique is well-studied in adult cells, but very little published research has been done using embryonics. And it's the latter application that has bioethicists up in arms.