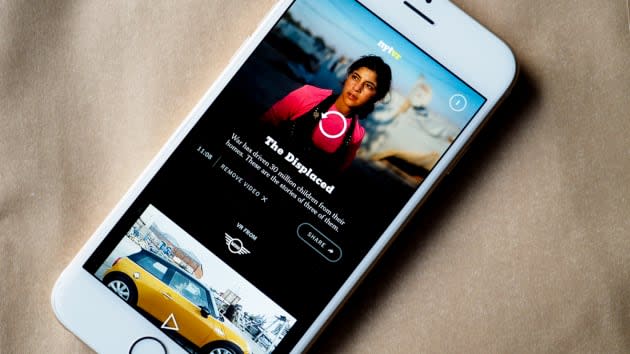

The New York Times VR app took me inside the news

I'm standing in the center of a rubble-filled classroom. The floor is ankle deep in books with overturned desks jutting up like volcanic islands in a sea of literature. At the chalkboard, a young boy is writing something. It's difficult to see what he's writing on the one item that establishes that kids used to learn in this room. I do know that the boy's name is Oleg and he's one of three child subjects of the New York Times' VR app (NYT VR) lead story, The Displaced. He starts telling me his story and I'm spinning trying to take in the virtual environment the publication has dropped me in. Everything is fuzzy at first while I adjust my iPhone in the Google Cardboard headset. Then after a few adjustments, everything lines up. It's not crystal clear, but the story starts to unfold without the technology getting too much in the way. That should be the end game for The New York Times. Tell stories without the tech getting in the way. The app is a good -- yet gimmicky -- start, but it'll need more adjustments to bring it into focus and really change the way we get our news.

The Oculus Rift announcement at CES in 2012 ushered in a new era of VR. The technology that stalled in the 90s was finally able to deliver on the Lawnmower Man promise of a truly immersive alternate reality. Since then game makers, journalists, developers, even Facebook (which purchased Oculus in 2014 for $2 billion) have been trying to figure out how to get this technology on our faces. The New York Times app is just the latest attempt and while my first inclination is to label it a simple gimmick, it has the potential to change how we learn about the world.

It won't replace text, photos or even video. The types of articles that would work in virtual reality are extremely limited. You're not going to see breaking news appear within the app (at least not yet). Journalists will not be running around with multi-angle camera rigs at the ready when they are dispatched to events. Instead, expect short narrative pieces like The Displaced, the tale of three children living with the aftermath of war and persecution. It can be a powerful story telling mechanism, but it's not perfect and because of that most people will use it once then forget about it.

The app requires a VR headset like Google's Cardboard, which the publication is giving to all of its subscribers either bundled with the paper or via coupon. But even with that and a smartphone (Android or iPhone) the experience can be sub par. Getting everything aligned can be frustrating. The 15 to 30 seconds needed to make the video look good was time I wasn't paying attention to the unfolding narrative. The text (a major part of the video experience) is difficult to read. It also only appears in certain areas of the video. I'm spinning in circles trying to find the subtitles during The Displaced. It's even more confusing when some of the dialog hasn't been translated. Instead of surveying the environment, I'm turning my head this way and that trying to find words.

When the text isn't there, the story is driven by audio and images (once I got it in focus) and is more powerful than I expected. The village in the South Sudan swamp and the food being airdropped into that area were particularly moving. The aircraft flying overhead added a sense of immersion that you can only get in VR. I had to look up to see the plane as it unloaded its humanitarian cargo and watched it fall to the ground with a series of thuds. But it's more than the main action that makes the app and how it presents the news important, it's the periphery. It's showing what you wouldn't normally see.

After the food bags hit the ground, groups rush out to claim their nourishment. It's easy to see how a single photo or video shot could manipulate the viewer's perspective of what's going on. Image framing could show a large group of people with only a few care packages available. Framed another way, the image could convey a story where a few people receive a large amount of aid. With VR, you see the whole experience. It's much more difficult to hide or manipulate what's happening within the scene.

That doesn't mean a journalist's bias won't influence camera placement. But it gives the viewer more control over what they are seeing. There's a lot of potential here. Even when you hand millions of subscribers a headset and offer an app that makes story telling more immersive it doesn't mean they'll get on board. And when they try it out, there are only two stories in the app -- there are also two ads. They have to pay for all that technology somehow. If you want something to thrive it needs to be nourished and after seeing The Displaced and the less intriguing Walking New York, converts are going to want more. If they don't get it, they'll put the app and Cardboard aside and forget about them.

The NYT needs to keep pumping these stories out to keep people enticed. It won't be easy.

Creating this content adds an entirely new workflow to publications. That's additional funds being put into a technology that may or may not add eyes to the main site. It's funds that might have to come from somewhere in the editorial budget. While people keep insisting VR is the future, the average person might not be excited about watching a video with something strapped to their head.

FUTURE IS NOW, MAYNE. The @NYTmag VR experience LIVE 😻 pic.twitter.com/4zJr8HuYFC

— Jenna //\\ Wortham (@jennydeluxe) November 6, 2015

The NYT can build the greatest VR article ever, but if it can't get the gear on its viewers faces, it doesn't matter. Plus it has to contend with users that try it out and got frustrated by current VR limitations. The NYT VR app opens up a wonderful new way to tell stories, but it will only look amazing when the end-user has dropped a few hundred dollars on a headset. Maybe the publication will help jump start the VR age with its plan to ship millions of low-cost Cardboards to subscribers. Just don't expect to see a lot of people spinning in their chairs for the news. At least not yet.