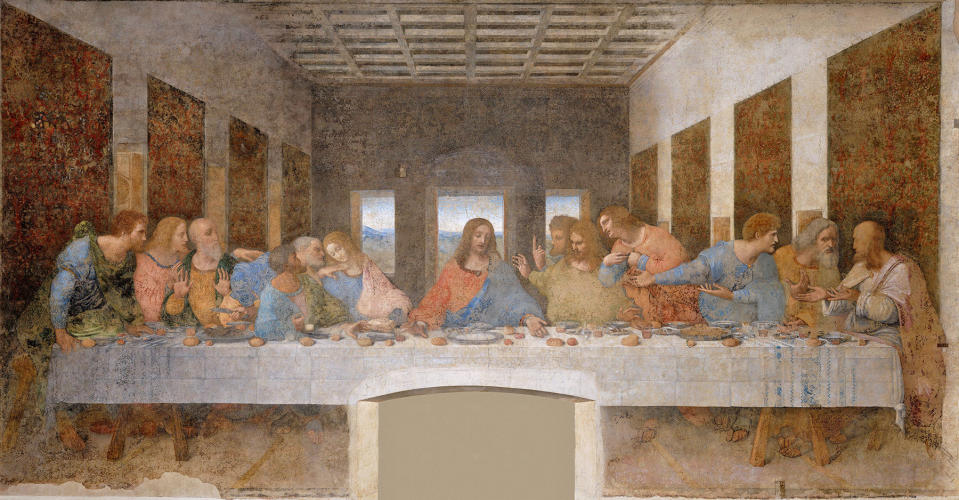

The unending fight to preserve 'The Last Supper'

“The last time,” every time.

In April, Italian marketplace chain Eataly announced it would sponsor the latest effort to preserve Leonardo da Vinci's painting The Last Supper. It's the perfect marketing partnership: A food company saves the most famous depiction of a meal for future generations. This excerpt is from its online announcement, titled "Eataly Saves The Last Supper":

"We are partnering with the Italian government to sponsor a game-changing installation. Italy's Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism has designed an air-filtration system in collaboration with top Italian research institutes to filter in cool, clean air into the convent every day (10,000 cubic meters compared to today's 3,500!)."

The state-of-the-art filtration system will be installed and active by 2019, in time to mark the 500th anniversary of da Vinci's death.

This is the latest in a long line of attempts to stave off the inevitable. Nothing man-made is permanent; it will all be dust, eventually. But The Last Supper is a particularly tragic example of man's impermanence. And the fight to save it has been laden with controversy, particularly in the modern era, as corporate sponsorship and claims to technology have muddied the waters of an already sensitive subject.

The work of preserving Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper began soon after its completion.

The artist, ever the innovator, used an experimental technique to paint the moment that Christ told his Apostles that one of them would betray him. The scene would typically have been painted on wet plaster, but this fresco technique was fast-drying and would have required him to work quickly. Da Vinci wanted to work slowly over a number of years, and so he applied his pigments to a dry plaster wall. The result was a painting that did not adhere to its surface, owing to both the artist's technique and Milan's humidity.

The Last Supper began flaking a mere 20 years after da Vinci completed it. And after the Renaissance period passed, subsequent occupants of the church treated the painting with disregard. In the 1600s, occupants cut a door into the bottom of the painting, eliminating part of the table and Christ's feet, which were composed to allude to the crucifixion. When Napoleon Bonaparte's troops used the room as a stable in the late 1700s, they threw fragments of bricks at the painting's faces. And during World War II, a bomb hit the church. The wall with the painting on it, however, survived intact.

Along with these indignities were multiple attempts to repair and preserve the painting -- seven distinct attempts in all. These ranged from incompetent to serviceable, depending on the expertise of the artist and the technology available at the time. In 1770, for example, Giuseppe Mazza repainted all the faces with the exception of three before he was stopped; the prior who assigned him to restore the painting was sent to another convent. Another restorer, Stefano Barezzi, attempted to remove the entire painting from the wall and transfer it onto canvas in 1821, permanently damaging the work in the process.

In 1947, restorer Mauro Pellicioli began a multiyear process to reinforce the painting and return it to something resembling its original state. He adhered the flaking paint to the wall with a colorless shellac resin. He then began scraping away earlier restoration work, leaving only the areas covering empty spots, where Leonardo's work was lost or unsalvageable.

"The shellac was applied to entomb what survived on the wall, to keep it in place into perpetuity," Michael Daley, director of ArtWatch UK, told Engadget.

This was meant to be a final, definitive restoration. And yet, mere decades later, another, "better" restoration of the painting would be attempted.

"There is a great prejudice for the new in restoration, which is problematic," said Daley. "It's always dangerous in life to rush into new technologies and be the first.

"In aeronautics, researchers have to get things right," Daley continued. "They can't afford for airliners to go down. But in art restoration, for all the great cultural importance of the works, the people who administer the restorations are not disciplined manufacturers; their activities grew out of craft traditions. And they can be amazingly casual."

Daley and art historian James Beck founded ArtWatch in 1991 as a watchdog organization -- a vocal, if small, contingency of artists and art historians that documents and protests what it views as irresponsible art restorations. Prior to its criticisms of The Last Supper's restoration, the organization's notoriety came from its criticisms of the Sistine Chapel renovation. They share common themes.

Taking place from 1980 to 1994, the Sistine Chapel restoration was necessitated, according to the Vatican, by soot and grime, which had built up over centuries by burning candles. In addition, there were cracks in the ceiling that would have ultimately affected the integrity of the work.

When the ceiling was reintroduced to the public in 1994, the majority of observers praised the restoration. The physical ceiling was repaired and reinforced to prevent future damage. And the frescoes were now filled with bright, previously unseen colors.

But perhaps they were now too bright -- brighter than they had ever been during Michelangelo's lifetime. The cleaners thought that Michelangelo had taken a uniform approach to painting the ceiling, that he had always worked buon fresco, adding illustrative details, like shadows and shading, while the plaster was still wet. So the cleaners assumed that anything not buon fresco was either grime or was added in by another artist, and they removed it.

It became apparent, however, that Michelangelo had painted much of the shadows and detailing on the ceiling al secco, after the plaster dried. And thus, all of these original details were destroyed during the cleaning. Now the figure in the Jesse spandrel is missing his eyes.

And the Jonah figure, which serves as a focal point of the entire work, is dramatically diminished by the lack of shadow and definition. Many figures in the painting now have a sort of washed out, rough appearance.

How could this have happened, no less to one of the most significant cultural works of the Western canon? Beck attributed it to the restorers' arrogance, that their confidence in knowing the artist's intentions and method led to the painting's ruin. The restorers began their work in relative isolation without consulting an outside, independent committee of art historians, artists or scientists. Beck pushed for this committee in 1987, when the ceiling was already half completed; one did convene later that same year, however, and filed a complimentary report.

"The new freshness of the colors and clarity of the forms on the Sistine ceiling are totally in keeping with 16th-Century Italian painting and affirm the full majesty and splendor of Michelangelo's creation," the report refuted.

Thus, critics were not able to halt what they saw as destruction of Michelangelo's work. But they were able provoke a response. To date, ArtWatch has still not been widely successful in preventing these sorts of restorations. But ArtWatch has seen success in changing the conversation surrounding restoration, from one that is overly laudatory to one that is initially suspicious.

It was difficult for interested parties to track the ongoing work -- the result of the restoration's sponsorship by Nippon Television Network Corporation. The network paid $4.2 million dollars to the project in exchange for exclusive rights to document and photograph the restoration. It seems, on its face, like a conflict of interest, to entrust the proper documentation of the restoration to a company that stood to benefit the most from a positive portrayal. A positive review of the restoration by The New York Times in 1990 noted that Nippon had made the restoration photos prohibitively expensive and had not yet provided the requisite before-and-after photographs that would address critics' concerns.

Thus, ArtWatch's dual, primary concerns are an overzealous approach to restoration using new techniques, which risks damages that cannot be reverted, and the influence of corporate money, which calls the ethics and motives of the restoration into question.

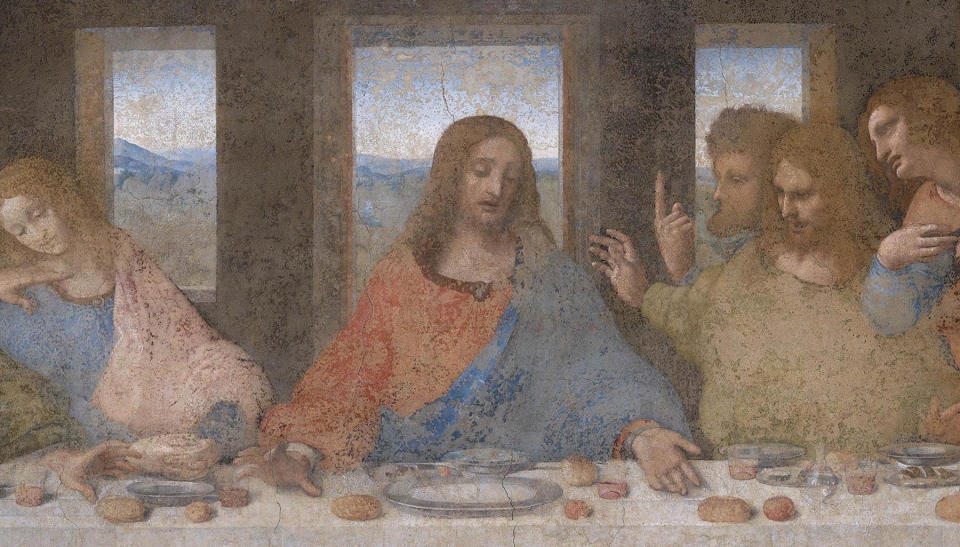

In 1978, Pinin Brambilla Barcilon began work on what was, once again, promoted as the final, authoritative restoration of The Last Supper. This time, rather than attempting to retain the work of prior restoration attempts, her goal was to strip it all away -- the shellac from the prior restoration included -- and get down to da Vinci's handiwork alone.

Only approximately 20 percent of the original painting had survived.

Barcilon viewed the painting through a microscope and then slowly, gently blotted the painting with solvent, using small bits of Japanese mulberry cloth.

The end result was a sad revelation: Only approximately 20 percent of the original painting had survived. There was, however, a trade-off: Barcilon uncovered many details, buried underneath the prior restorations, that were once thought lost. An orange here. A hand's definition there. A face with different dimensions and expression.

The missing parts of the painting, meanwhile, were filled in with beige, to give an indication of what the painting once looked like. In Barcilon's own words, from her book Leonardo: The Last Supper, which documented her entire process:

"Where the pictorial film was missing, the initial procedure was to reintegrate the image based on neutral tonal reduction (neutro), intended to create an ideal background of homogeneous color for the original fragments. In the interest of achieving greater legibility and unity, a method of reintegration that approximated the surrounding color was adopted later. Executed in watercolor, the reintegration was particularly laborious and delicate because the surface absorbed the color unevenly, requiring repeated applications and a gradual buildup of tonal intensity."

The book explains and rationalizes the before and after for every part of the painting; it is exhaustive in its attention to detail. To illustrate, here is an excerpt of the before state of Thaddeus (the middle apostle in the above photograph):

"Before the latest restoration, the figure generally appeared dark, and the facial features were undefined. A dark diagonal stroke roughly designated the eyes. The hair blended in with the gray field of the wall behind the figure, and the almost indistinct volume of the hair was flattened in an abbreviated mass."

And here is an excerpt of the after state of Thaddeus:

"Numerous and unexpected recoveries of original material emerged from beneath the blanket of repaint, especially in the face and the hair. The hair reacquired its initial volume, modulated by wavy locks threaded with subtle highlights and delicate white brushstrokes, while a soft gray glaze skillfully emphasized the hairline. The facial features proved leaner and purer, even on a chromatic level."

Clearly, this restoration was a labor of love and devotion; one could hardly spend 20 years nose to nose with something without it being so. Critics, however, took issue with several points of this restoration, the first being its necessity. If so little of da Vinci's original work remained, reasoned critics, then why strip away the record of prior restorations, which had become a part of the painting's history? What was the sense of having something that was more Barcilon's watercolors than da Vinci? Shouldn't the more historically noteworthy restorations have remained instead?

"Restorers have a professional imperative, rather than to reflect upon what they're seeing, to do something about it," said Daley.

One might speculate that the corporate sponsorship, this time of tech manufacturer Olivetti, may have also increased pressure to act -- to be proactive for the amount of money that was being spent rather than do nothing at all.

Science captured the imagination of Western civilization in the wake of World War II, which was won, in part, due to the superior technology of the Allies.

"In the second half of the 20th century, restorers, who themselves were technically and scientifically naive, became enthralled and envious of the authority of scientific people and disciplines." said Daley. "Science is used to make their activities more respectable than they might be. Restorers try to maintain the scientific aura of impregnability."

Science, in other words, can be used as a cudgel and conversation-ender to give cover to untested techniques that may not, in actuality, be all that scientific. And because there are still ongoing, internal debates over major aspects of restoration -- such as whether solvents or soaps are even safe to use -- one might conclude that a restoration is often not worth the risk. A risk, Daley claims, was taken with The Last Supper.

"The restorers painted the bare wall in these watercolors, and it's made the painting into a kind of modern decoration," lamented Daley.

ArtWatch is not alone in its criticisms.

"[The restorers] decided to proceed without even conducting the proper analyses to determine how much of the original painting remained," said Mirella Simonetti, a Bologna-based restorer, in a 1995 interview with The New York Times. "And now they show these remaining crumbs, these plates and glasses, and say it is Leonardo."

In a final cruel irony, Tom Hundley, who wrote about the restoration for the Chicago Tribune in 1999, made the following cautionary point: The painting, no longer protected by the shellac or any overpainting, was now more vulnerable to the elements and environment than ever before.

That brings this long, winding journey up to the recent announcement of Eataly's new air-filtration system.

"Works of art currently housed in the Cenacolo Vinciano Museum have undergone material deterioration caused by factors such as indoor air pollution, biological contamination, mass tourism, and variability in microclimate conditions," Sara Massarotto, Public Relations & Social Media Manager for Eataly USA, told Engadget. "L'Ultima Cena is no exception, and has suffered greatly from these environmental conditions through the centuries.

"In particular, the humidity emitted by the wall da Vinci used as his experimental canvas has put significant pressure on the painting, especially if the air and temperature are not carefully filtered and monitored," continued Massarotto. "This is why restrictions to protect the fragile nature of the space -- such as limiting visits to only 1,300 individuals per day -- are in place."

ArtWatch's primary concern is neither for the system itself nor its necessity; both have been verified by a wide range of academic sources outside the museum, from the Polytechnic University of Milan to the University of Milan-Bicocca.

Rather, the problem is whether these changes have been necessitated by current, irresponsible practice and if these changes will enable rather than discourage similar practice in the future.

"The question that is often ignored is: 'Why are serious systems of air filtration necessary?'" said Ruth Osborne, director of ArtWatch International, Inc., in an interview with Engadget. "For something like The Last Supper, air filtration had to be recommended due to previous restoration efforts that have botched the works. The continuous restoration is making the work fragile. There is also added pollution due to the increasing influx of visitors allowed into the space than is healthy for the stability of the art.

"An air filtration system is not to be seen as a cure-all for works of art in danger." continued Osborne. "It seems the maximum of 25 visitors to Leonardo's Last Supper is still in place, though the question remains: Will those in charge decide this is reason enough to enable more to fill the space?"

Additional visitors equate to additional contamination, and this could damage the work further. Art does little good in a climate-controlled storage unit, where it cannot be seen by the public. But what happens when art, paradoxically, is too fragile to be seen? And regardless, all measures to preserve and maintain the work, whether or not it is on display, cost money. Corporations, vested interests or not, are often a necessary concession.

It's a circular catch-22 that will continue unabated, because art continues to age, and today, restoration is an established industry. One can study it at a university and earn a degree in it. There are entire conservation departments at art museums dedicated to its study and implementation. It's a matter of approach, however: to take radical measures under the cover of scientific inquiry or to err on the side of inaction, in fear of damaging something beyond repair.

In the case of The Last Supper, centuries of irreversible damage have already been done. Damage compounds damage. Mistakes pile up. And additional damage, Daley supposes, will be done in the future.

"I haven't the slightest doubt that within the next 20 years, someone else might look at The Last Supper and say, 'That's not satisfactory.'" said Daley. "There will be another excuse. You can't stop people wanting to be the person who saved the greatest art in the world."

Image credits: Unknown / Wikimedia (Milan bombing); Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism / ArtWatch UK (The Last Supper / Sistine Chapel ceiling).