Scientists find a much faster way to classify our cells

The technique may lead to new ways of spotting and treating diseases.

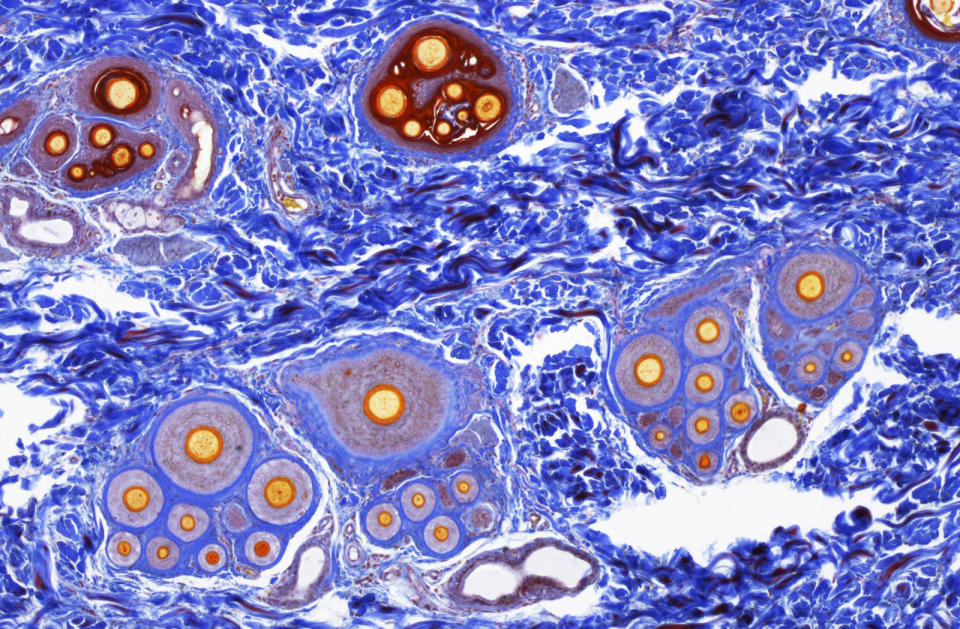

Researchers have created a new technique for identifying cell types much quicker than ever before, a finding that could improve disease diagnoses and treatments. While there are many types of cells in our bodies (red blood cells, spindle neurons, etc.), scientists don't know the exact number, because current microscope techniques are slow and laborious. By tagging cells with molecular markers, however, the team was able to read their unique RNA combinations like a bar code at exponentially higher speeds.

Here's how it works: Cells are first placed into wells, where molecular markers attach themselves to each RNA strand. The process is repeated, and eventually each cell type has a unique combination of tags on its RNA molecules. The team can then break the cells open chemically and read back the sequences of tags. "We came up with this scheme that allows us to look at very large numbers of cells at the same time, without ever isolating a single cell," Dr. Jay Shender told the New York Times.

The team tested it using 150,000 cells from Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm), a tiny worm that has been model for biological research since the 1960s. They not only identified the 27 known cell types, but were able to break them down into groups with mildly different gene arrangements. That includes 40 different neuron types, including a rare example that only forms one cell in very few worms.

We came up with this scheme that allows us to look at very large numbers of cells at the same time, without ever isolating a single cell.

Those results are exciting, but the system doesn't work all the time. With roundworms, for instance, it failed to identify 78 different types of previously identified neurons. "Of course, there is more to do, but I am pretty optimistic that this can be solved," said Rockefeller University's Cori Bargmann, who wasn't directly involved in the study.

The research also must be adapted to the complexities of the human body. Nevertheless, it's very promising, particularly for the Human Cell Atlas initiative being funded in part by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. That aims to map every cell in the human body, providing a baseline to compare healthy cells with diseased ones.

The study could reveal signature for pathology, better record cell-to-cell interactions and help scientists interpret genetic variants. The ultimate goal is to "discover targets for therapeutic intervention and ... drive the development of new technologies and and advanced analysis techniques." Much like with new gene sequencing techniques, it could help push medicine and treatments to a new level.