What is a ‘Game of the Year’ edition, anyway?

More often than not, it's just a marketing ploy.

Every year, game publishers put out Game of the Year editions, typically chock full of all the downloadable content that's come out since the initial release along with new packaging to proclaim its "of the year" status. Some titles even get new content to entice customers into buying an older game.

But what, exactly, does it mean to be a Game of the Year? And according to who exactly? Is there a regulating body that protects consumers from games that were not, in fact, that good? You might think of the "Game of the Year" term as an implication of quality, right? It turns out that — like most marketing — it's largely meaningless. And countless gaming outlets name their own "Games of the Year," further confusing things.

Even more confoundingly, The Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences (AIAS) hands out its own award to a title, regardless of platform, that best entertains users. The AIAS award isn't the one you'll see on a Game of the Year Edition, though. "The award honors the single title that captured the hearts and minds of the global game community and distinguished it as the best of the best," AIAS president Meggan Scavio told Engadget in an email. "To be even more specific, it could be due to impressive storytelling, technological innovation that really impacts the future of game design or even immersive world building that awes our membership," she said.

The AIAS Game of the Year award is like a seal of approval or badge of quality, says Scavio. It's like an Oscar or Emmy, only for video games. That's what publishers want you to think of when you're buying a repackaged Game of the Year Edition, of course. These products may indeed have received an official Game of the Year award from organizations like AIAS, but they just as likely may have been named such by a random website or journalist.

It's hard to take the concept of a Game of the Year Edition seriously when mediocre titles like Operation Flashpoint and AFL Live get these editions in years where there are far better games on the market, like Grand Theft Auto III and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, respectively.

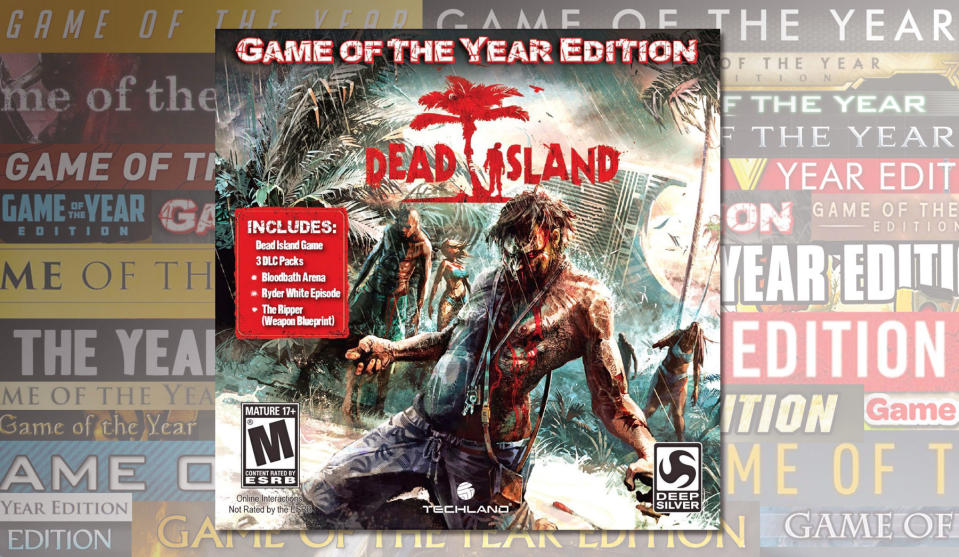

Case Study: Dead Island

When Dead Island was released in 2011 after a hefty delay, one of the only outlets that gave it any attention was GameCritics. "The game was troubled by releasing too early before it was ready for prime time," the site's EIC Brad Gallaway told Engadget in an email, "and it left a lot of reviewers with a very bad taste in their mouths, (which) was understandable. We played a more finished version later on and we really loved it. In fact, we named our game of the year."

Gallaway said that the site got a lot of heat for the pick, but that he still stands by the choice. "I think that eventually we were proved correct because it had an incredibly successful run with fans despite the trouncing reviewers gave it," he said.

Shortly thereafter, Dead Island's PR team got a hold of GameCritics and said they wanted to work together to promote a Game of the Year Edition repackage. "We were the only website on earth that gave it top honors from what I understand," said Gallaway. "We were happy to oblige and we had talked about doing a contest, giving away a bunch of copies, and all that sort of stuff."

That's the last Gallaway recalls talking to anyone from Dead Island. The Game of the Year Edition did end up on retail shelves, though, but GameCritics was not credited on the packaging. "My guess is that PR didn't realize how much of a joke people thought we were for choosing the game," he said. "They probably didn't think our website had enough cred to slap our name on the box, although they were still using our endorsement to justify this edition."

Which means that, at least in this case, publishers wanted an actual "Game of the Year" designation from an actual outlet, even if they didn't admit which one on the packaging. "That's pretty much where it ends," Gallaway said. "PR never brought up the subject with us again and they never responded to our requests for clarification about the situation, or about crediting us on the box. Kind of sucks that these guys got to put the label on their product and sold a ton more copies, while we got ridiculed and couldn't even get credit where credit was due."

Definitive Editions as a sidestep

We spoke with indie game developer Mike Bithell (Thomas Was Alone, Subsurface Circular) about his perspective on releasing Game of the Year Editions. While Bithell has sold repackaged boxed editions of his games, they've never been called "Game of the Year," mostly because he hates tooting his own horn. "We're often perhaps too modest in hyping our own games," he said during a phone call, "but a boxed definitive edition, with included DLC and such, can really help our games get out to a new audience."

Digital-first games like the ones Bithell makes tend to get purchased by gamers with Steam or other services like it. Packaging them into a physical copy — whether its a collector's edition or just a repackaged "definitive" edition — helps find customers who might only buy games at Walmart or GameStop.

Publishers get more exposure for a game this way, too, and customers get a more complete game that includes DLC they don't actually have to download. "I love being able to call a game finished (with a definitive boxed edition) so I can move on to the next," said Bithell.

The final cut

Ultimately, titles that get Game of the Year Editions may or may not be very good. Even while most of these repackaged titles have been legitimately named a Game of the Year, you never know who made that decision. While the AIAS provides specific artwork for games it's given its own award to, not all publishers are going to back up their claim with proper credit. Sure, you'll get some fun extras for the game that might have cost extra if purchased nearer to the actual release, but it may or may not be truly worthy of the Game of the Year moniker.