Researchers may have detected signals from the universe’s first stars

Evidence suggests they began to form 180 million years after the Big Bang.

The early development of our universe is still quite a mystery, but in a new study published today in Nature, researchers describe what may be evidence of when the first stars began to form. After the Big Bang, which took place some 13.7 billion years ago, the universe was dark, hot and full of high-energy particles. Photons couldn't survive, but after around 380,000 years, the universe cooled enough to allow light to actually stick around. That's when the cosmic microwave background (CMB) came to be. It's our universe's first surviving radiation and researchers have looked to it in order to learn more about the earliest years of our universe.

Researchers have theorized that we might be able to see when stars began to form by looking for a dip in the intensity of the CMB. The reasoning is that once stars started forming, they would have heated up the hydrogen gas permeating the universe. When that gas heated up, it would have absorbed radiation from the CMB, causing its intensity to drop. That's not something we can see with our telescopes, but it's something we can detect in radio signals. The problem is, those signals would be incredibly faint and easily drowned out by the radio signals we produce here on Earth as well as the many being flung at us from the Milky Way. "Sources of noise can be 10,000 times brighter than the signal -- it's like being in the middle of a hurricane and trying to hear the flap of a hummingbird's wing," said the National Science Foundation's Peter Kurczynski, who oversaw funding for the research reported today in Nature.

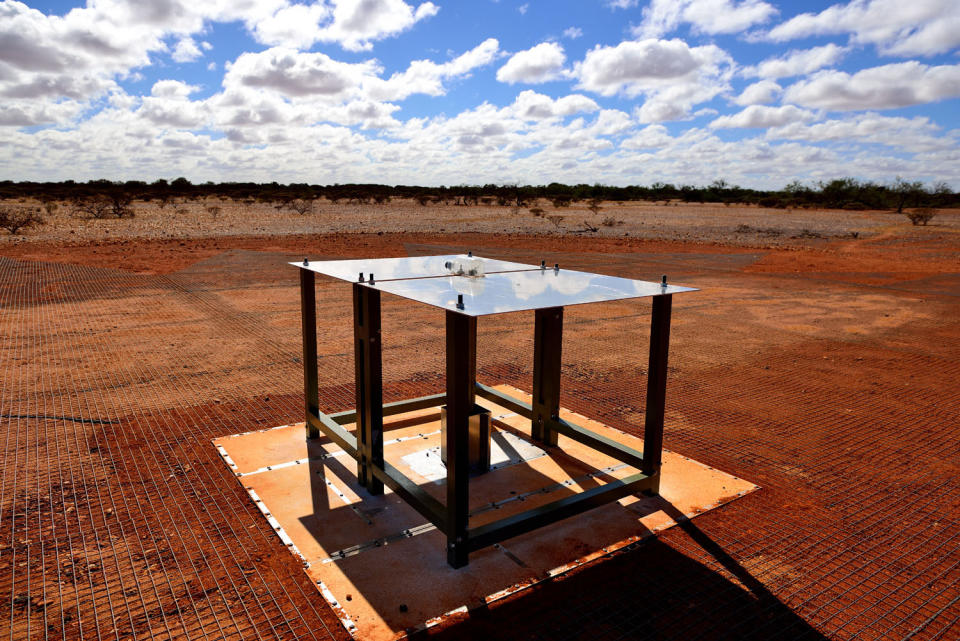

But scientists at Arizona State University and MIT set out to find the faint signals that mark the earliest star formation and they did so with a rather small radio antenna (pictured above) placed in an Australian desert. The remote location helped minimize interference from human-made radio signals and let the team hone in on the faint signals they were looking for. And in 2016, they spotted them -- a dip in CMB radiation marking when stars first began to light up around 180 million years after the Big Bang. "This is exciting because it is the first look into a particularly important period in the universe, when the first stars and galaxies were beginning to form," Colin Lonsdale, director of MIT's Haystack Observatory, said in a statement. "This is the first time anybody's had any direct observational data from that epoch."

The team spent over a year confirming their findings -- changing the position of their radio antenna, using a different one and changing the instruments' calibrations. The signal was observed each time. But not only did they detect the signal, they found that it was around twice as intense as they expected, suggesting the early universe's hydrogen gas was much colder than previously thought. In another paper also published today in Nature, Tel Aviv University researcher Rennan Barkana argues that dark matter could explain a colder universe. "If that idea is confirmed," Judd Bowman, lead author of the first study, told the NSF, "then we've learned something new and fundamental about the mysterious dark matter that makes up 85 percent of the matter in the universe. This would provide the first glimpse of physics beyond the standard model."

These findings still need to be confirmed through separate experiments, but if other researchers come up with similar findings, we're in for some pretty exciting science. "Basically, it's worth two Nobel Prizes if the detection is correct," Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb, who wasn't involved in the study, told Gizmodo. "One for the first detection of hydrogen from when the universe was 100 million years old, and the second for detecting new physics."