Stomach wearable could replace the need for invasive probes

Advanced signal processing makes largely abandoned "EGG" devices feasible.

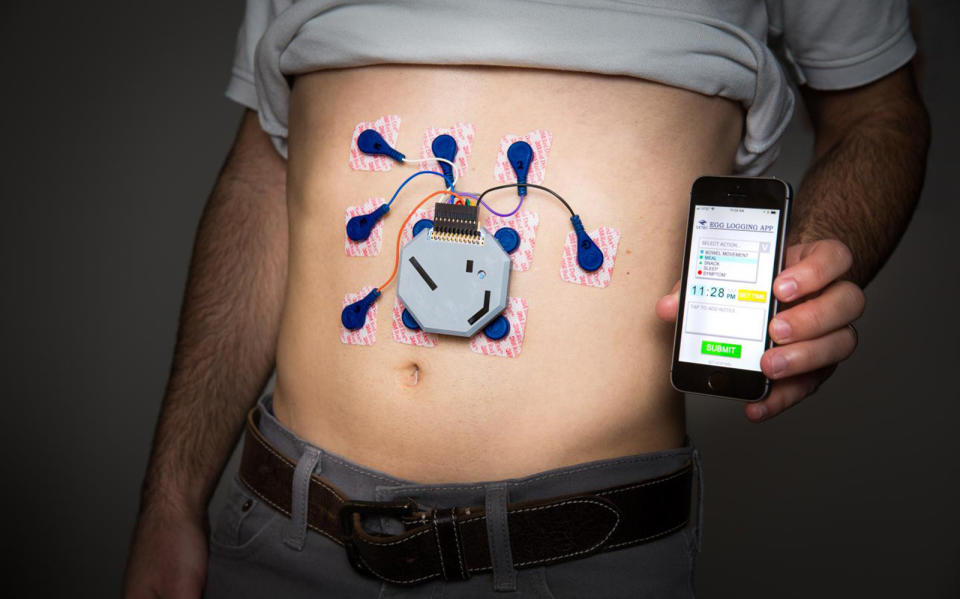

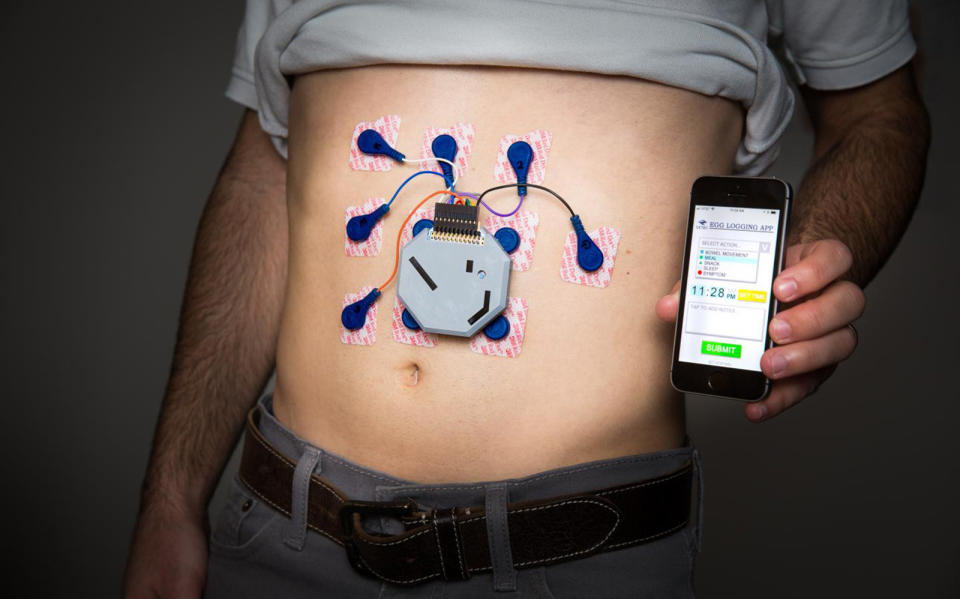

Researchers have created a wearable monitor that can track your stomach's electrical activity for signs of digestion maladies. Called electrogastrography (EGG), it's like an EEG for the GI tract, and was used briefly in the '90s but abandoned due to a lack of usefulness as a diagnostic tool. UC San Diego scientists are trying to resuscitate it with improved hardware and, most importantly, algorithms that help filter out noise. The results so far are promising, and if perfected, it could help doctors diagnose gastro-intestinal problems without the need for invasive probes or even a hospital visit.

EGG works by scanning electrical signals in the stomach that control gastric contractions. Any oscillation rates different from a normal three cycles per minute can signal GI tract maladies. The system had a moment in the 90s, but is rarely used by gastroenterologists nowadays. That's because signals from the skin-mounted electrodes can be distorted by patient movement and complex stomach interactions.

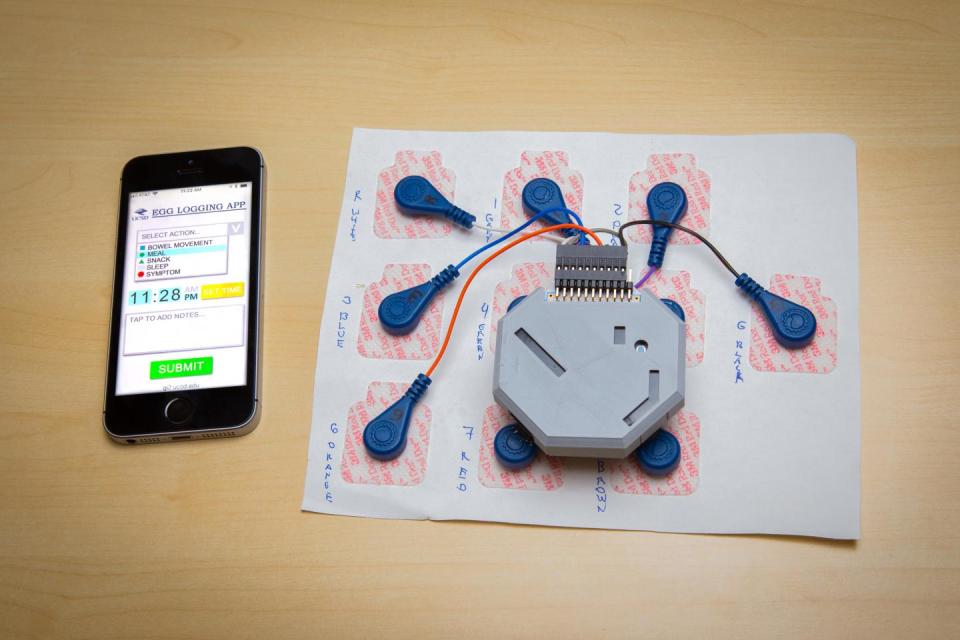

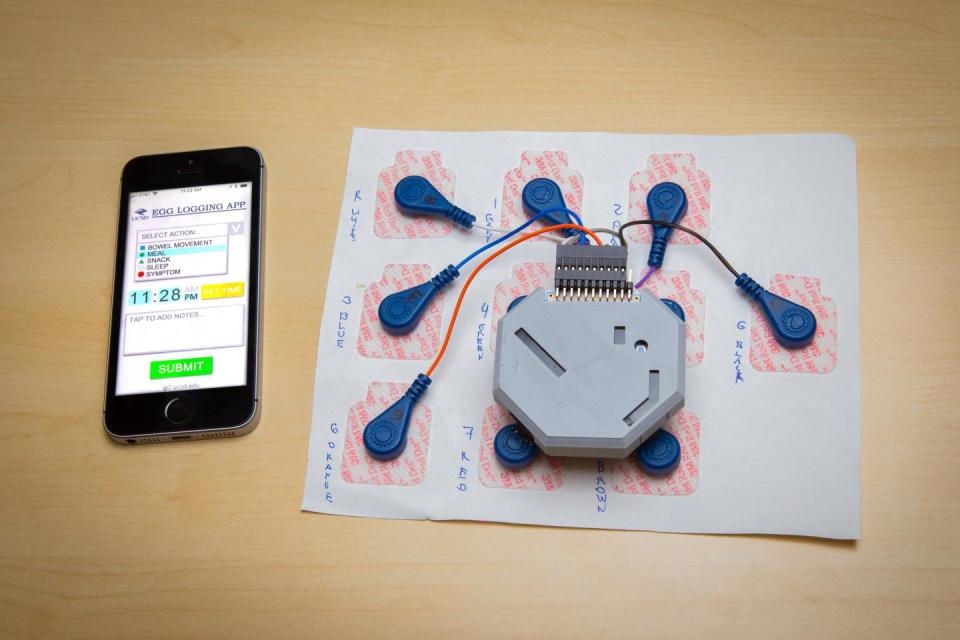

To fix those issues, UC San Diego's team optimized the electrode positions and increased the number of scanning channels from one to 25 in the high-resolution device, or eight in a portable version. More critically, they developed algorithms that remove electrical noise to isolate the true stomach wave signals.

In a small trial with 11 children they tested the high-resolution device against an invasive manometry test, in which a cathetor is inserted the nose to measure stomach contractions. The EGG results closely lined up, while the older, single-channel system matched the manometry in just three of the eleven subjects.

"A gastroenterologist can quickly see where and when a part of the GI tract is showing abnormal rhythms and as a result make more accurate, faster and personalized diagnoses," said lead author Armen Gharibans. "Until now, it was quite challenging to accurately measure the electrical patterns of stomach activity in a continuous manner, outside of a clinical setting."

On top of helping physicians find GI tract issues, the device could be worn over a long period to help healthy patients or athletes perfect their dietary regimes. It might also be useful for patients with diseases like diabetes that cause secondary digestive issues.

Critics have questioned whether EGG data is valuable, even if accurate, saying that gastric contractions are too general to use as a diagnostic tool. To counter that, the UC team is now testing 25 adults with digestive disorders and found promising correlations between electrical signals and specific problems like abdominal pain, bloating and heartburn. If the final study bears out those results, it could bring relief to a host of stomach-churning issues.