Microfluidic sensor could spot life-threatening sepsis in minutes

Doctors could have a better chance of preventing septic shock.

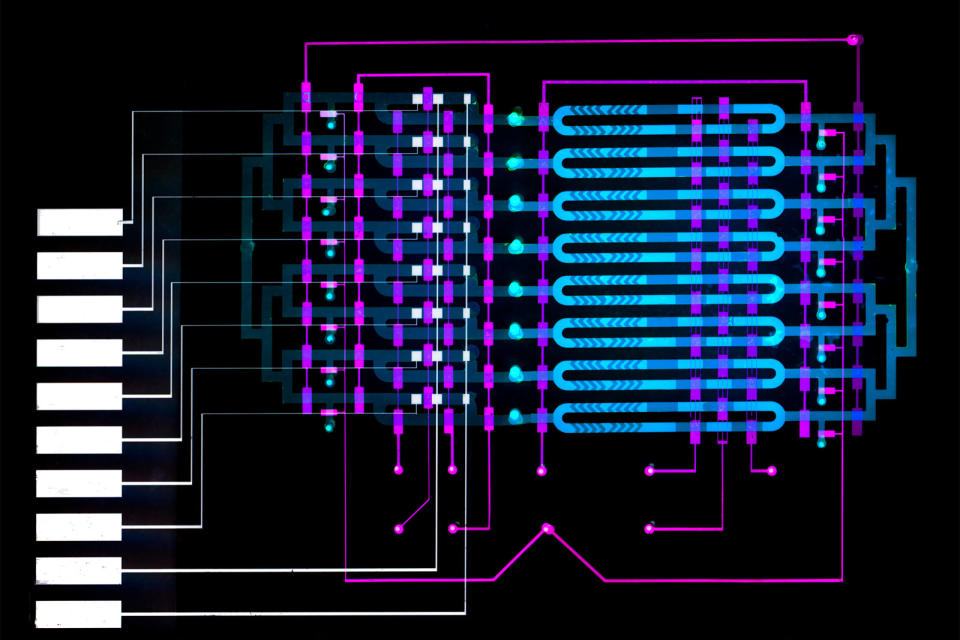

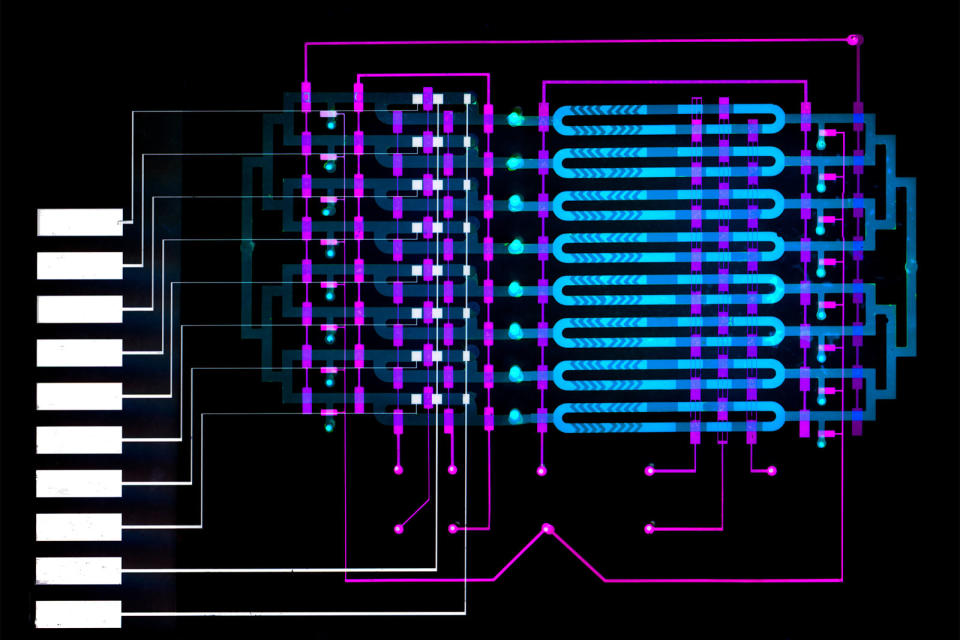

Sepsis (where your immune system starts a chain of inflammation reactions) is potentially deadly, especially if septic shock leads your organs to fail, but diagnosing that in a timely fashion is still difficult or requires an unwieldy device. Thankfully, MIT researchers might have a way to identify sepsis before it's too late. They've designed a small microfluidic sensor that could detect sepsis in roughly 25 minutes, or enough time for doctors to start treatment. It might not look like much, but it promises far more sensitive detection than before.

Scientists know that levels of the protein interleukin-6 (IL-6), produced in response to inflammation, tend to rise in the hours before other sepsis symptoms reveal themselves. They're normally too weakly concentrated to spot quickly, but the microfluidic sensor doesn't have that issue. One of its fluid channels includes antibody-laced microbeads that mix with a blood sample to snag the IL-6 biomarker, while another channel attaches those beads with the biomarker to an electrode. When you run voltage through the electrode, it produces a signal every time one of the IL-6 beads passes through. You could detect even minute increases in IL-6 over the course of the test, and you just need more channels (MIT's example has eight) to process samples in parallel.

The device is not only compact, but should be inexpensive compared to existing portable systems. And crucially, you don't need to provide a huge sample. A single finger prick of blood is usually enough versus the milliliter current systems need.

This technology isn't ready for the hospital. There's plenty of refinement in the pipeline, though, including plans to detect other sepsis biomarkers (there are over 200 FDA-approved examples) like IL-8, C-reactive protein and procalcitonin. If and when this becomes a finished product, doctors might catch sepsis early enough to save lives, even in health care facilities where existing systems wouldn't be practical.