HBO’s 'The Inventor' explores how Theranos happened, but not why

Alex Gibney can’t fill the gaps in Theranos’ fascinating story.

From the beginning of The Inventor, HBO's upcoming documentary about the failed blood testing startup Theranos, director Alex Gibney ties the story of founder Elizabeth Holmes to another notable tinkerer: Thomas Edison. Like Holmes, he tried to "fake it till he made it," throughout his career. After buying the rights to an early incandescent bulb design, he spent years claiming he'd solved the light bulb problem, long before he finally created one that lasted over 1,200 hours. Unlike the Theranos founder, though, he succeeded before his failures caught up with him.

It's no wonder that Holmes named Theranos' mysterious testing box "Edison." It showed the level of success she aspired to, and inadvertently, it hinted at the corners she'd willingly cut to get there. Theranos went from being worth around $9 billion to less than nothing, after the Wall Street Journal reported that the company's "revolutionary" blood testing box didn't actually work.

The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley, which premieres on HBO on March 18th, fits right within Gibney's wheelhouse chronicling crooks and frauds, like his classic documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room. But it's also another exploration of the power of belief, something we've seen in Going Clear, his Scientology film, and his deconstruction of Steve Jobs' cult persona, The Man in the Machine.

"I can't say I thought about [the role of belief] in advance, but it's clearly something I'm interested because it keeps coming up over and over again," Gibney said at a SXSW media event. His friend, writer and producer Lawrence Wright, coined the term "the prison of belief" to explain how blind faith can easily lead people down a dark path. That's a phrase they used to describe Scientology and its followers in Going Clear, but Gibney believes it also applies to Elizabeth Holmes.

"She believed she would get there [creating a simple blood testing device], and therefore she was entitled to fake it till she made it," he said. "But I think it's that belief that allows you to go forward and to lie effortlessly and also be cruel to people who oppose you." That's something she shares with Steve Jobs, who was known to call up and berate journalists when he disagreed with their Apple stories. "That sense of belief is a real danger," he added.

The Inventor gives us a glimpse into the inner workings of Theranos, thanks to some internal footage (including promotional material shot by fellow documentarian Errol Morris); CG renderings of the Edison box; and interviews with former Theranos employees, from a receptionist to the head of product development.

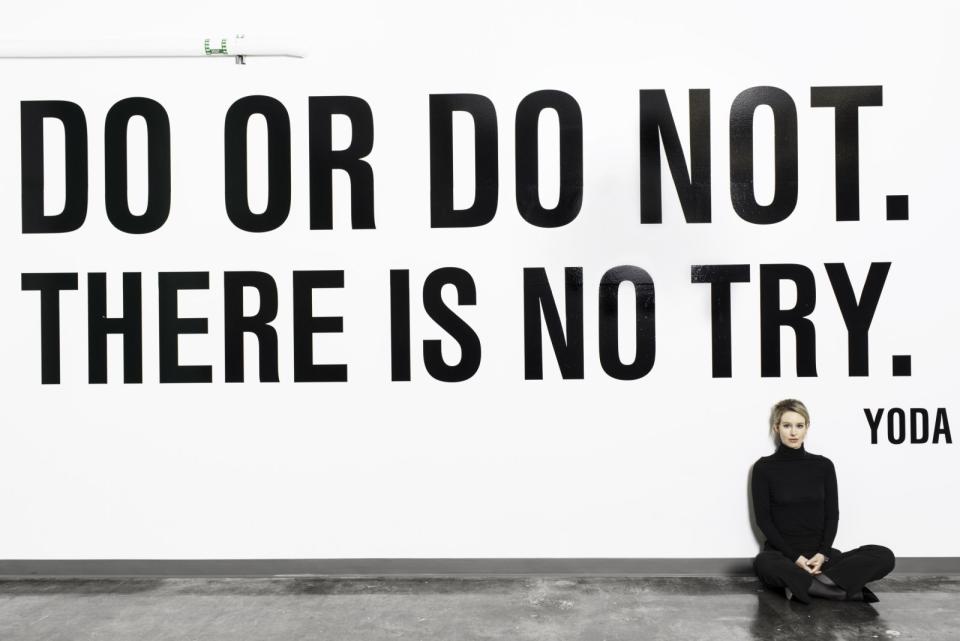

The film builds upon WSJ reporter John Carreyrou's book, Bad Blood, which details the company's founding and brief-yet-tumultuous life, but it doesn't unearth anything truly groundbreaking. And even though Holmes' is the star of the story -- with her wide unblinking stare, Jobs-ian black turtleneck and alien speech cadence -- we don't learn much more about her side of the story. The Inventor desperately calls for an on-camera interview with Holmes, where Gibney could have pushed her out of her comfort zone. Unfortunately, she never agreed to one.

Instead, Holmes invited Jessie Deeter, one of the film's producers, to an awkward five-hour dinner. "I was definitely being interviewed, it wasn't going the other way," Deeter said during the media event. "She wouldn't let me take notes and wouldn't let me record the conversation. I'm sure it was recorded one way, for sure. She wanted all the information she could get, she wanted to know who we were talking to and what Alex's questions would be."

During that dinner, Holmes said critics were maligning her because she was a woman, even though men were allowed to fail over and over again in Silicon Valley. When I asked Gibney if she has a bit of point, he was quick to note that Theranos is different than most startups because "she was putting people's' lives at risk." Holmes is held to a higher standard, he said, because she was dealing with human healthcare. Her role as the young genius female founder was also a major reason Theranos attracted plenty of attention early on. "I think it was an inspiring idea," he said. "But when you cross the ethical line having to do with people's health, you can't really hide behind that."

If you've only casually followed the Theranos story, The Inventor has enough juicy tidbits to leave you slack-jawed. How did an unknown health startup with an untested founder get so much support from early investors like Tim Draper? (Spoiler: He was a family friend.) How did Holmes convince the likes of Henry Kissinger and former US Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis to join Theranos' board? How did so many people willingly work for a company where they didn't fully understand its flagship product? The film doesn't answer most of these points, mostly because he never get Holmes' actual point of view, but it's still a fascinating exploration of Silicon Valley privilege and excess.

Holmes wasn't the only notable person Gibney couldn't get on camera. Errol Morris, who shot some slick commercials for Theranos (like the one above), didn't reply to any calls or letters for comment. In the footage Gibney unearthed for The Inventor, Morris's fawning and loving treatment of Holmes looks laughably naive today. When the two ran into each other during an industry event, Morris firmly refused to talk about Theranos and told Gibney "you can't make me." Even going off the record was too much. "For God, there is no off the record, and he can be a very unforgiving person," Morris said.

In the end, Gibney couldn't quite let go of the connection between Elizabeth Holmes and Steve Jobs. "The one lesson she never took from Jobs was what he learned from his biggest failure," he said. The re-invented "Steve Jobs 2.0" surrounded himself with people like Avi Tevanian, who served as Apple's chief software technology officer; Jon Rubenstein [former Apple hardware head]; and superstar designer Jony Ives. "Those people were great at what they did and they could also tell Steve Jobs no. They were kind of a feedback loop. And I think he learned to listen in ways that are constructive, it's incredibly valuable. But that's not a lesson Elizabeth learned."