In Mars One we trust

Mars One promises to send humans on a one-way trip to the red planet, with the intent to colonize, by 2027. Once the first four people leave Earth for Mars, there's no turning back, no panic button, no chance to return home. This aspect of the trip isn't just for drama -- it's a core tenet of Mars One's technical feasibility. CEO Bas Lansdorp believes that it's possible, using current technology, to land and sustain human life on Mars.

But the systems that would power a human settlement on an alien planet are ridiculously complex. They're so complicated that Lansdorp isn't yet sure what they will actually be. This lack of ready research has mired Mars One in controversy, thanks to a recent one-two credibility punch: First, a 2014 research paper from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology concludes that the program is not realistic. Second, a series of articles for Matter magazine calls into question the feasibility of Mars One financially, scientifically and ethically. Still, Lansdorp promises to send humans to live on Mars, but he can't yet say how. He wants the world to trust him.

The science

Mars One plans to send four people to Mars in 12 years, with the intent to launch subsequent manned missions and colonize the planet. Its Technical Feasibility section promises that the mission is possible using "existing, validated and available technology." Lansdorp places his faith completely in the companies that will build the necessary systems; Mars One won't manufacture any hardware itself.

Lansdorp, who founded his own wind-energy company in 2008, freely admits he doesn't understand the scientific details behind Mars One's proposals. "On a high level, yes. On a detailed level, absolutely not. I'm a mechanical engineer, so I know about the scientific principles in general," he says.

This is one reason Mars One will outsource all technological work: Currently, Paragon Space Development Corporation is working on Mars One's life-support systems. Paragon is preparing a report on the technical aspects of life on Mars, due out before the end of April. This will be Mars One's first attempt at explaining the dense science behind its space-survival concepts.

But for now, Mars One makes huge, impossible-sounding claims, but doesn't offer answers to technical questions, which is one reason MIT dove in itself.

"The Mars One mission plan, as described on their website and by Mr. Lansdorp on several occasions, is not feasible," write Sydney Do and Andrew Owens, the researchers behind the MIT study. They argue that Mars One's technological conceit is simply not viable. "Significant technology development is required before we can even land and sustain humans on Mars, much less support a growing colony," they say.

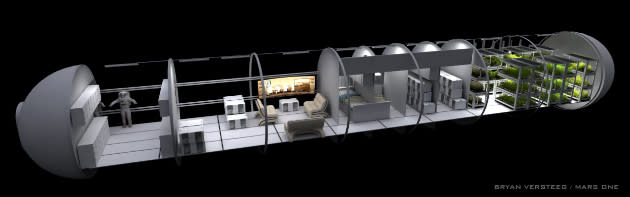

A Mars One habitat, in concept form

Do and Owens found three main issues with Mars One's plan: In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU), plant growth/atmosphere management and spare parts manufacturing. ISRU means using existing elements on Mars to help sustain the crew. For example, Mars has high levels of nitrogen, an element necessary for human survival.

"Significant technology development, testing and validation efforts are required before ISRU technology can be relied on to support a human crew -- particularly a crew that has taken a one-way trip, since there is no contingency plan if something goes wrong," Do and Owens write.

As for plants and atmosphere management, the Mars One plan includes implementing 200 square meters of crops for food, for four people. The idea of growing food on Mars is admirable, but the amount of plants poses a problem, Do and Owens say. Four crew members would not produce enough carbon dioxide -- a natural byproduct of breathing -- to sustain 200 square meters of crops, so there would have to be some type of atmospheric control in place. Mars One recognizes this problem and proposes using carbon dioxide from the Martian atmosphere to combat it. But, this raises another issue: As plants process carbon dioxide, they create oxygen, which would build up to dangerous levels in the habitat, meaning it would require a venting system.

"This oxygen-removal technology has never been implemented in space, and is not 'validated and available' for application in a human colony on Mars," the researchers say.

Growing plants on Mars

Finally, the colonization aspect of Mars One's plan is daunting. The humans there would have only the supplies that they bring, meaning if the habitat breaks down and they can't fix it, they're dead. The Mars One Roadmap proposes launching primary and backup life-support systems alongside each subsequent mission, plus spare parts for the existing crew. The second crew brings parts for itself and the first crew; the third crew brings parts for itself, the second crew and the first crew, and so on. In terms of financial sustainability, this is a nightmare -- 3D printing won't cut it, Do and Owens say.

Lansdorp tackles this problem using a best-case scenario: "That's again assuming the spare-parts strategy of the International Space Station, which is when a system breaks, you replace the system. While if a system breaks on Mars, you find the component that broke down and replace the component. That might be a spring of a gram or half a gram, instead of throwing away a system that might be five or 10 kilos."

Parts larger than a gram, or even as large as 10 kilos, could also break down. Lansdorp recognizes that "spare parts is a problem," but it's not his problem -- Mars One will hire aerospace companies to figure out the necessary systems.

Do and Owens still aren't convinced that this is possible using current technology. To eradicate the resupply issue, they say it would be necessary to establish mining and manufacturing ecosystems on Mars, which would be costly in terms of time and money.

An outside view of conceptual Mars One habitats

The researchers think it's possible that humans will one day reach Mars -- it just won't be the Mars One way. "One of the interesting aspects of the Mars One organization is that for an organization proposing a technical endeavor, they do not spend much time talking about how they will achieve it," they say. "In addition, we have seen a few cases where Mr. Lansdorp seems to be confused or misinformed about some of the technological solutions that he proposes."

In the end, Mars One is the company making bold claims about living on another planet, and so the burden of proof falls to Lansdorp and his team. Still, he says the upcoming Paragon report isn't meant to prove the feasibility of Mars One.

"We have already enough support to show that," he says.

The response

Regardless of whether Mars One agrees with the MIT research, its response to criticism does not always inspire faith.

"He didn't do his homework at all. ... You don't do this in science."

Dr. Norbert Kraft is the chief medical officer for Mars One. For nearly two decades, he's conducted research for NASA, the Russian Space Agency and JAXA, the Japanese space agency, specializing in the psychological and physiological effects of long-term spaceflight. He's a fellow of the Aerospace Medical Association and holds an M.D. from the University of Vienna, Austria.

"The issue is that, first, it's not an MIT study," Kraft says about Do and Owens' work. "A student, an undergraduate student, wanted to make a presentation at a conference. My problem with him is his scientific approach. As a scientist, you just can't read a website and make the rest of the stuff up."

There's one clear problem here: The MIT researchers are not undergrads. Do and Owens are Ph.D. candidates in aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, each with Master of Science degrees in the same field at MIT. Lansdorp also mentions that he believes Do and Owen are undergraduate students, but says he can't be sure.

Dr. Norbert Kraft

Apart from Mars One's assumption that the researchers are inexperienced students, Lansdorp disregards the study because he says it uses incorrect data and doesn't offer any solutions to proposed problems. However, Mars One changed two sections of its website based on Do and Owens' paper -- altering the wording of its overall goals and changing the expected amount of plants needed on Mars from 50 square meters to 200 square meters. Also, the researchers asked Mars One for data during their study, but Mars One didn't offer any. Remember, it's all about trust at this stage.

Support for Mars One is not universal: Gerard 't Hooft, a Nobel-winning theoretical physicist and an ambassador to Mars One, says that it would take 100 years to settle Mars, not 10, and at least 10 times the amount of cash Mars One seeks. Chris Hadfield, an astronaut and the first Canadian to walk in space, asserts that Mars One is "disillusioning" people, and argues that it doesn't even address basic ideas about space travel. Elmo Keep is the reporter who spoke to Hadfield about Mars One; over a yearlong investigation, she's penned a series of critical articles about the program for Matter magazine. She does not support Mars One.

"It's actually really damaging to legitimate space exploration because it makes the entire field by association look really foolhardy," she says.

Keep finds numerous issues with Mars One's plans, including that "they have no money. They have no revenue stream. They barely have any employees." In 2013, Mars One announced that 200,000 people had signed up to be shipped to Mars, though Keep argues that number is actually closer to 2,000. Perhaps 200,000 people signed up to receive email alerts about Mars One, but they definitely didn't all intend to travel to the red planet, she says. "It's a total lie," she says. "It's just an outright fabrication."

Lansdorp offered Keep a chance to see Mars One's list of 200,000 candidates, but with stipulations that she couldn't agree to: "His conditions were that he sees the story first and if he doesn't approve of the story, they're not going to share the list. ... The whole thing just completely fell apart." And that's before even digging into the money issues.

The money

"The technology will be there, as long as we have enough money," Kraft says.

Kraft may be convinced that money will solve his program's issues, but financing Mars One sounds almost as impossible as the science: Lansdorp says he needs just $6 billion, while conservative estimates place a NASA Mars mission (with a return trip) around $100 billion. 'T Hooft says something like Mars One would cost, at the very least, $60 billion. The savings stem from the idea that Mars One is a one-way trip, and there's no need to build systems for a return launch.

"I think that returning is impossible," Lansdorp says. "Of course not from a physics point of view, but from a practical point of view, I think it's impossible."

Even if costs skyrocket as the MIT study suggests, Lansdorp has said that Mars One will eventually pay for itself because it will be a huge media event -- think Big Brother on Mars. People and networks will pay to see this whole process unfold, he thinks. Last week, Lansdorp told NPR that Mars One would be worth $45 billion in media revenue, roughly 10 times the amount brought in by the Olympic Games.

Human Martians would live in tube-like structures.

"What universe -- what place are you from?" Keep asks. "If someone could create a $45 billion entertainment property, they would do it."

Lansdorp doesn't specify how much money Mars One has, but he says it has the cash to sustain operations for now. So far, the program has pulled in $784,380 from donations, merchandise sales and crowdfunding, according to its Donate section. This includes $313,744 from a Mars One Indiegogo campaign that ended in early 2014 (it asked for $400,000). Mars One recently lost a contract with production company Endemol, which was supposed to establish that Mars One television show.

Mars One is not-for-profit, but it receives some funding from, Interplanetary Media Group, a for-profit company it owns. Plus, Mars One completed a successful investment round in 2013. Lansdorp has a signed agreement with a new group of investors, though he won't disclose the amount just yet, other than to say it's a "significant amount of money."

Mars One offers no salary to current candidates. In fact, Lansdorp asks participants to turn over any money earned from press appearances to the company, rather than keep it for themselves. He plans to offer a "revenue share" program, though he says that many candidates prefer to funnel their money directly into Mars One. And some of them are putting their money where their Mars is -- a former candidate explains the selection process to Keep as follows:

"You get points for getting through each round of the selection process (but just an arbitrary number of points, not anything to do with ranking), and then the only way to get more points is to buy merchandise from Mars One or to donate money to them."

Mars One asserts that a candidate's points don't influence whether that person will be selected for the final mission. Kraft, the leader of Mars One's selection process, says he's focused on finding people who learn quickly, who understand the risks of a one-way mission and who won't abandon their team if they get homesick.

"If you don't understand the risks, you put everyone in jeopardy who's with you," Kraft says.

The future

A lot of Mars One hinges on what-ifs and unknowns. For now, the company has narrowed its pool of Martian candidates to 100. Eventually, they'll get that down to 24 candidates, each of whom will receive an offer to be employed by Mars One. They'll be trained, and eventually the program's first four permanent astronauts will be selected.

"We don't pretend to have the solutions for every problem. We just say that we know that there are solutions for every problem."

Of course, the plans could change. In fact, they already have. Last week, Lansdorp announced that Mars One would be delayed by two years, with the first human Mars landing in 2027. And there are plenty more changes to come, Lansdorp promises.

"I'm absolutely sure that by the time our mission is implemented and humans land on Mars, that it will look nothing like the pictures that we show on our website and many of the systems will be completely different from what we have proposed," he says.

Mars One is under intense scrutiny, and Lansdorp suggests this nit-picking might stem from his own openness about the project's goals, that he might be getting punished for being transparent. NASA, for example, most likely wouldn't even discuss its plans at this point, since everything is really still in the "concept phase," he says.

"We don't pretend to have the solutions for every problem," Lansdorp says. "We just say that we know that there are solutions for every problem."

[Image credits: Mars One]