Video games are tackling mental health with mixed results

Mental illness occupies a strange place in video games. After centuries of misdiagnosis and misinterpretation, we've begun to comprehend the reasons behind disorders and their prevalence in modern society. Recent research shows that roughly one in five American adults suffers from some form of mental health issue each year. When it comes to the media, though, these conditions are frequently misrepresented and misunderstood, and video games in particular lean on lazy stereotypes and tropes. Mental illness is used as a motivation for villainy, thrown in as an "interesting" game mechanic or mischaracterized as the sum and whole of a character's personality. There's a worryingly pervasive stigma surrounding mental conditions, and as one of our most dominant art forms, video games need to do a better job in portraying them.

Gamification

By all accounts -- including our own -- Darkest Dungeon is a fantastic game. It's a side-scrolling RPG in which you send a team of four heroes into various dungeons in search of gold and glory, but more importantly, it's an intriguing portrayal of the effects of trauma on the psyche. These dungeons are cruel and trying, and the game recognizes that in its leveling and affliction systems. Each character has a "stress meter" that, when full, hands them some form of "affliction" like paranoia, selfishness or masochism. At the end of missions, characters are then given "quirks" by the game, which can be positive or negative depending on how the dungeon crawl went.

Having these meters is a simplistic, but effective way of showing that stress is something normal that affects us all. You can "treat" characters between missions to lower stress and cure afflictions and quirks, but do nothing, and the scars left behind seriously affect characters' psyches. The other side of these quirks, though, is that some are actual conditions like alcoholism, bulimia and claustrophobia, while others hint at illnesses like "egomania" (i.e., narcissistic personality disorder) and "compulsion" (obsessive–compulsive personality disorder). There's nothing wrong with that, but because the game places these disorders alongside "curio" manias and phobias like automatonophobia (fear of false sentient beings), hagiomania (obsession with sainthood) and satanophobia (fear of demons), it's a little troubling.

The stress meter is a simple, but effective way of showing it's something normal that affects us all.

"I actually think stress meters are great, and if anything they are anti-stigmatizing," says Tracii Kunkel, a clinical psychologist at the Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Orlando, Florida. (His views are his own and do not necessarily represent the VA or any VA programs). Kunkel works extensively with veterans diagnosed with severe mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder and chronic/severe PTSD. As an expert in the field, he's all too familiar with the "shame" projected onto patients by society. In addition to aiding the veterans as they adjust to life with SMI, he also provides training on mental illness, stigma and self-stigma (how individuals internalize perceptions of their mental illness).

"We all experience stress," Kunkel continues, "and it has an impact on our mental and behavioral states. ... Portraying a character with mental illness in a video game isn't a problem in regards to stigma; in fact if done properly, it really could be a positive force. Just as long as it is not done as a stereotype or shown in a way that you see the mental illness and not the person who happens to struggle with mental illness."

There's a fine line between accuracy and inaccuracy, or positivity and negativity. In other games that have played with similar ideas, such as Eternal Darkness, "sanity" is tracked by a meter. It's clear that quantifying someone's "craziness" is not helpful, and it shows the fine line developers walk when tackling such issues. You could argue that, as Eternal Darkness heavily plays on HP Lovecraftian motifs, its portrayal of mental health fits with its world. A common theme in Lovecraft's work is that enough contact with otherworldly stimuli can cause even the most rational of humans lose their grasp on reality. Whether you want to use the writing of someone with such infamously dated and nihilistic views as Lovecraft to defend modern game mechanics is another question.

Villainy

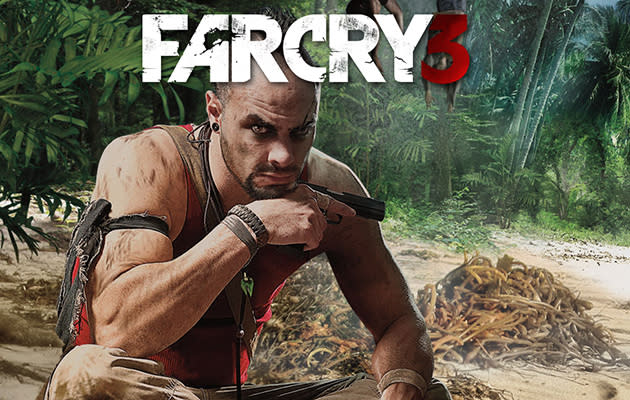

From Far Cry 3 and BioShock to Final Fantasy and Call of Duty, video games are full of antagonists whose sole reason for villainy is mental instability. Many creative industries use "insanity" as a crutch to avoid thinking of any actual motivation for wrongdoing, but few with such raw abandon as video games. Just search for "crazy video game villains" or some skew of that phrase and you'll find list after list ranking them. "Insanity is a great trait for a video game villain," writes IGN freelancer Seth Macy, "because their motivations for evil can then easily be explained."

"Mental illness is a cop-out, a cheap tool used to get right to the violence."

Sure, except, insanity does not make someone evil, and the term "insane" is frequently used as a synonym for those suffering from real, treatable conditions and disorders. "Mental illness is a cop-out," says Kunkel, "a cheap tool used to get right to the violence, because the assumption is that people with mental illness have no control of their behaviors." This flippant attitude to mental illness is something we're all guilty of from time to time, and it does nothing to erase the stigma surrounding it.

Far Cry 3's antagonist, Vaas Montenegro, is a mainstay of these lists, and a great example of this "criminally insane villain" trope. He's a man with no motivation other than to inflict pain for pain's sake, no character beyond his instability. He's completely flawed. No matter how wrong someone's actions are, they're always motivated by something.

"The 'crazy villain' trope isn't just in video games," explains Kunkel. "Whenever a shocking act of violence occurs, we immediately start looking for the mental illness. I understand the need people have for an explanation in the case of traumatic events, but mental illness should not be the default. ... The number one damaging myth about mental illness is that people with mental illness are inherently violent." Put simply, equating mental illness with violence is not accurate, and it's truly harmful to those suffering and recovering from conditions.

Best intentions

The problem is, even developers with the best intentions can get things wrong. Jumpy Car ADHD is an Android game that hopes to help improve the understanding of ADHD. It's specifically targeted at those affected directly or indirectly by the disorder, and it backfires. Although the game gives out some accurate information between levels, the developer made some key errors in designing the experience that could lead someone diagnosed with the disorder projecting shame onto themselves.

An ADHD child worrying about being blamed for being "hyper," it's safe to say, is not helped by the developer calling the enemies "hypers," or by reading the instruction "you must avoid the bad hyper." In addition, the playable character is called "crazy car." The result, explains Kunkel is that "the child with ADHD who does relate to the car is taught that he/she is crazy and bad."

Narrative perspective

A subtler integration of mental illness is the use of narrative perspective, which can be a powerful empathetic tool. Putting a reader, viewer or gamer inside another person's mind allows them to experience reality from someone else's viewpoint. Examples of first-person narrative are everywhere, but it was used to stunning effect in Knut Hamsun's Hunger, a 19th-century novel that puts you in the mind of a struggling writer during his decline into poverty and starvation. Given video games routinely have you roleplaying as a character, the medium is a perfect fit for the technique.

2013's Depression Quest is a great example of how to achieve empathy and understanding through perspective. It's a text-based game in which you must make choices on how to handle your condition, which helps improve the player's understanding of clinical depression. It's also the only title Kunkel brought up when asked about accurate portrayals of mental illness in video games. Of course, it's difficult to judge other titles by a text-based game's standards, but there are action games that are attempting to use a narrative lens to accurately convey the effects of mental illness.

Hellblade is one such game. Its protagonist, Senua, is suffering from schizoaffective disorder after her tribe is murdered by a Viking raiding party. As the game is viewed through her eyes, we see the reality Senua has created for herself through illness. Common traits of the disorder, such as visual and auditory hallucinations, scattered speech and thoughts and paranoid delusions are all represented in the game.

Although at its heart Hellblade is a third-person fantasy combat game, it's striving for realism in the areas that matter. Developer Ninja Theory -- best known for DmC: Devil May Cry -- is working with Paul Fletcher, professor of health neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, to ensure an accurate depiction of the condition. Fletcher notes that "games in which the player sees 'madness' as inexplicable, chaotic and uncontrollable are simply reinforcing a stereotype, just going with the herd instinct." To avoid this issue, Ninja Theory has worked with Fletcher throughout the project's lifespan. This began with some simple advice on "the nature of the symptoms," but quickly expanded into more than a Q&A. "They were interested in the many ways in which perception and experience can change in the setting of severe mental distress and, following conversations about this, how normal perceptual systems may work and how they may go wrong in all of us."

"Games in which the player sees 'madness' as inexplicable, chaotic and uncontrollable are simply reinforcing a stereotype."

From these discussions, Ninja Theory developed a solid understanding of the condition, and began, with Fletcher's assistance, to work with groups of people that have suffered or are suffering from schizoaffective disorder in order to gather their experiences and ensure that their narrative ideas are in line with what's possible. In an early demo shown to journalists at Gamescom, hallucinations such as visual shifts or conflicting voices are blended into the narrative through cutscenes and gameplay.

Despite the developer's obvious desire to get things right, its handling of mental illness still worries Kunkel. "I will have to see the game when it gets released, but it feels right now like they are using mental illness as a tool to drive the game and making the illness the focus, rather than Senua herself." Kunkel does say he's "truly impressed" with Ninja Theory's approach, and has a "great respect" for Fletcher. "I think Hellblade looks like it is going to be a great view into what someone's first psychotic break may look like," he adds, but "such breaks are only part of the experience of schizophrenia."

So there's an obvious danger that this integration of mental illness into a combat game can devolve into gamification or, even worse, be used exploitatively as a way to shift copies of an otherwise typical combat game. "I don't have a problem with the combat, which I see, in its demands for complex manual skills, as a part of the gamer's enjoyment and a way of personifying the danger which Senua feels," says Fletcher. "Of course, one might worry that the game could equate violence with mental illness, but the story is much more one of a person whose problems have arisen from violence done to her and who is herself far from violent."

This integration of violence and combat into Senua's psychotic break does trouble Kunkel, though. "When the most significantly damaging myth about mental illness, and schizophrenia in particular, is that 'these people' are violent and not in sync with reality," he explains, presenting a character "who either lives in a constant psychotic break, or goes into breaks, where she perceives people as demons and lops off their heads with a giant sword," is not helpful. Kunkel recognizes that the character is fighting a hostile force, but says, "The fact remains that they are suggesting that she does not see reality and attacks violently."

Ninja Theory has shown a great deal of willingness to adapt its ideas in order to achieve not only realism, but also sensitivity. If the development team is able to frame its action hooks, narrative and characterization correctly, then it will have achieved something special. "It is extraordinarily rare that someone might be offered an opportunity to guide a character suffering these experiences and, through doing so, to perhaps gain an understanding and empathy," says Fletcher.

Kunkel says he's looking forward to Hellblade, in spite of his misgivings. Right now his experience of the game is through development diaries and trailers, of course, so his concerns are just that: concerns. Ninja Theory is very early in the development phase. Although Hellblade could be just as stigmatizing as past games that have misused "madness" as a selling point to sell games, there's also the potential for it to do a real service to those living with mental illness. Fletcher believes that, although it's not Ninja Theory's aim, an accurate portrayal of schizoaffective disorder could actually make the game a success. "If it's done well, and sensitively," he says, "indeed, it's a great selling point."

[Image credits: Bandai Namco (Pac-Man); Paper Relics (Phrenology diagram); Red Hook Studios (Darkest Dungeon); Ubisoft (Far Cry 3); Dr. Ivo Pinto Applications (Jumpy Car ADHD); Zoe Quinn (Depression Quest); Ninja Theory (Hellblade)]