MIT researchers develop ingestible sensor to measure vital signs

Stethoscopes listen to your body. These acoustic devices have been around since the 19th century and are still the norm for auscultating or examining the internal sounds of your body. But a team of researchers at MIT have developed an ingestible sensor that could measure your vital signs from the inside, specifically from the gastrointestinal tract. The new sensor, packaged inside a silicone capsule that's the size of an almond, is expected to make both short and long term assessments easier on patients. Beyond hospitals, it could also help monitor soldiers and assist athletic training programs.

The field of measuring vital signs has seen some improvements over the years. Apart from ECGs and electronic stethoscopes, there are wearables that help track a patient's heart rate. But the researchers point out that these methods require skin contact and can be incredibly uncomfortable especially for trauma patients like burn victims. Through their ingestible device, they intend to eliminate the need for any external contact with the body.

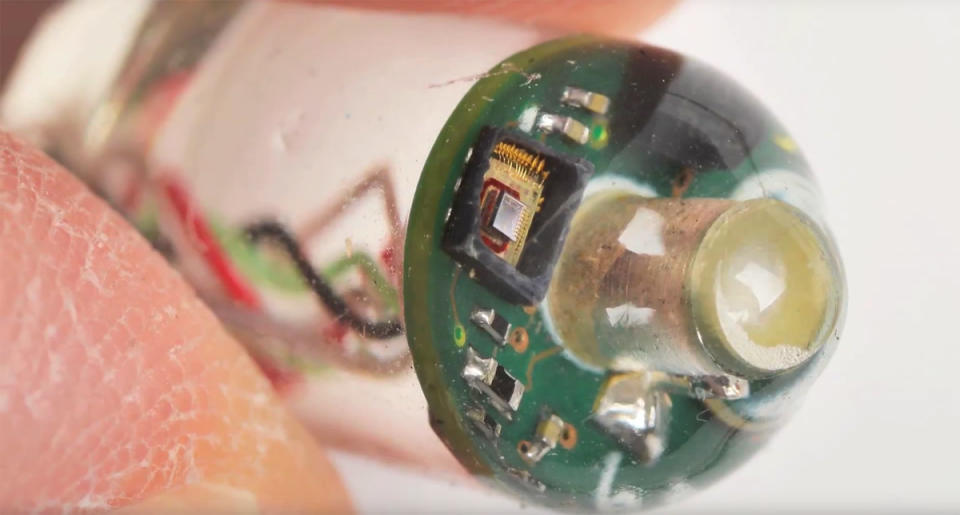

"What we did with our technology is identify components that were compatible with ingestion," Giovanni Traverso, a research affiliate at MIT's Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and co-author of the paper that introduces the tech, said in the video below. "These are very small microphones similar to the ones that are used in common cellphones and actually listen from within the body and [can] extract the heart rate and respiratory rate."

The microphones pick up sound waves from both the heart and the lungs, along with other noise that comes from the digestive tract. So the research team devised a signal processing algorithm that sorts through the clutter of sounds and differentiates between the heart and breathing rates. The signal can then be transmitted to a receiver as far as three meters away. Once inside, they expect the capsule-like sensor to stay in the tract for a day or two. But anyone who might need a long term analysis would have to pop these sensors on a regular basis.

[Image credit: Image: Albert Swiston/MIT Lincoln Laboratory]