I drove around Pittsburgh in a self-driving Uber

What's surprising about riding in an autonomous car is how boring it can be.

"Did you do that or did the car do that?" I first asked that of my self-driving Uber's "safety driver" when the car pulled out of the lane it was in to go around a pedestrian on the side of the road. I asked it another half-dozen times during the 30 minutes I spent as a passenger in one of Uber's autonomous cars, which are hitting the streets of Pittsburgh today. Nearly every time, the answer was: "The car did that."

Indeed, my time as a passenger in the self-driving Uber as it drove around downtown Pittsburgh was blessedly uneventful -- and in that relative safety and peace, I got an up-close look at what the challenges will be in making autonomous vehicles a widespread reality. I even got behind the wheel to "not drive" the car for myself.

For starters, it's important to note that I never once felt like the car made any unsafe maneuvers. It obeyed the speed limit, left plenty of space between it and the car in front of it, took turns slowly and smoothly and generally behaved like an excellent citizen in vehicular society. It decides on speed first by determining a safe driving distance from the vehicle in front of it, and then by going as fast as the speed limit when it was able to. Uber's engineers are also able to call out roads in which the car can exceed the speed limit to drive safely with the flow of traffic.

All told, it was a pretty boring ride -- aside from the fact that a freaking computer was driving me around downtown Pittsburgh. That's all the more impressive when you consider how much harder making a self-driving car operate around a city is compared to on the highway (like Tesla's autopilot feature does).

A freaking computer drove me around downtown Pittsburgh.

The times when my safety driver had to take control were less about the car doing something unsafe and more about it being confused about what its many sensors and cameras were recording. For example, the car didn't know how to deal very well with a truck that was double-parked. It read the truck as a vehicle stopped in the road, but it didn't have the context to know that it wasn't going to move anytime soon, so we just sat behind it until the driver pulled around it.

The car also had a tough time dealing with a four-way intersection -- while an autonomous car will obey the letter of the law, humans don't. So, with safety as a top priority, the car sat at the stop sign, waiting for crossing cars to come to a complete stop before it would enter the intersection. But most people out there don't come to a complete stop at a stop sign, so we just sat and waited while multiple cars crossed in front of us, glancing curiously at the strange bed of sensors on top of the vehicle.

Uber's cars will likely learn these intricacies sooner than later, and I got to see examples of that learning on display in my drive. Apparently, when you're stopped at a red light in Pittsburgh, it's customary to let the first car across from you take a left turn if they need to before continuing straight through the intersection (it's called the "Pittsburgh left," appropriately). The autonomous cars thus are programmed to take a little pause before continuing through an intersection when a car across from it has its left blinker on. That's not about driving "right" or "wrong" -- it's about knowing local rules of the road and respecting them. Every area these cars go into will have their own quirky rules like this that they'll need to learn.

The few hiccups I encountered didn't really detract from the experience; the overall ride was a smooth as I've ever had with a human driver behind the wheel. The autonomous system is finely tuned to provide a smooth and safe ride, and it never accelerated or decelerated in a way that made me feel uncomfortable. If you've taken a cab around any major city, you've probably experienced some car sickness from a driver with a heavy foot on both the brake and gas, but there was none of that here.

I'm someone with a rather sensitive stomach, but I felt fine for the rather lengthy ride. In fact, the ride almost felt too smooth, too in control. Like a computer was driving -- which it was. That's not a bad thing, but you can definitely tell the difference between a human behind the wheel and an autonomous system.

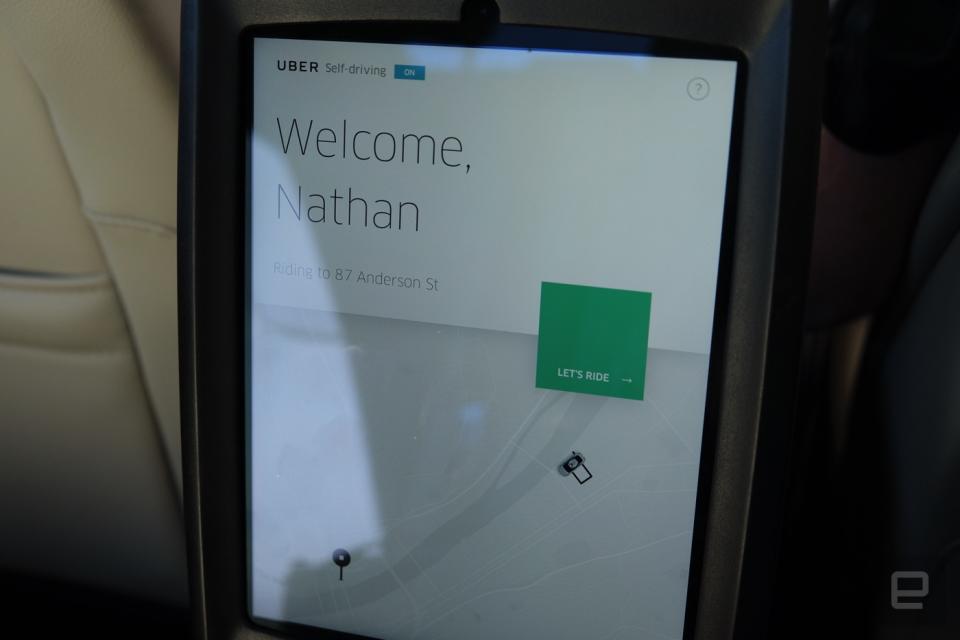

While sitting in the back of the Uber, I could look at an iPad mounted to show the riders some details on the car. You can see how far you've driven autonomously, the current speed and a graphic showing the movements of the steering wheel and when the brakes are applied. But most interesting was a view of what the car's radar system is seeing at any given moment. You can see cars, buildings, pedestrians and anything else in range of the car. It'll satisfy the curiosity of people interested in how the car works as well as provide some transparency and possible security to people skeptical about the system.

After cruising around Pittsburgh for a bit, I was offered my own chance to get behind the wheel. At first, I thought I was just getting a look at what the driver sees while they're behind the wheel, but nope -- I was getting a chance to sit up front while the car drove me around. The most interesting thing about that experience was the strange awareness I needed to keep while letting the car do its thing. I was tempted to look around and take in the sights of the city because I felt totally comfortable letting the car do its thing.

Getting behind the wheel wasn't any more nerve-wracking than riding in the back, because I was in complete control of the car.

Of course, the system is not even close to ready to have a driver totally check out, so I kept my hands touching the wheel and a foot ready to tap the gas or brake so I could take over. Fortunately, it's dead-simple to take control of the car: Moving the steering wheel or applying any pressure to the brake or gas will deactivate the autonomous driving system. I took over the car a few times, mostly just to see how it worked, and it was easy to both drive as normal and then hit a button near the shifter to put the car back into autonomous mode.

It's not surprising that full manual control is so easy to activate, but it makes sense that Uber would want the press to see first-hand how easy it is to snap the car into your control. That said, I could definitely see a situation in which a "safety driver" couldn't help but tune out a bit during a long shift behind the wheel. It's also not the easiest thing to keep your foot hovering over a pedal and hands lightly gripping the wheel without accidentally engaging with them.

The fundamentals appear to be in place for Uber, here in Pittsburgh, at least. But there's a long way to go before its cars can navigate all of the city, let alone other cities. A number of Uber engineers and spokespeople I talked to made it clear the focus was to build out Pittsburgh first, both in terms of increasing the area that autonomous cars could travel as well as fixing little oddities like its performance at four-way stop signs. Other cities will likely come in the future, depending on how the pilot goes, but right now all thoughts are focused on Pittsburgh.

One of the big challenges for Uber will be learning more about how the cars deal with inclement weather. That's one of the reasons it's testing in Pittsburgh -- between the complexity of the old city's layout (small streets, lots of one-way roads, lots of congestion) and the fact that it sees all kinds of weather, there will be a lot to learn from testing here. Uber engineers feel that if they can master Pittsburgh, they can make the system work pretty much anywhere. (I'm thinking both Boston and Manhattan will make for a serious challenge.)

Good luck mapping out Boston and Manhattan, Uber.

But it's not clear exactly how Uber will deal with bad weather. The team said they've tested in rain and had success thus far, but I wasn't able to get a straight answer when I asked about how it'll recognize and account for snow. It seems that it'll be up to the safety driver to decide when to engage the autonomous features, and I have a feeling that in the winter these cars will be operated in traditional fashion to be on the safe side.

As much as the pilot is to gauge Uber's technical prowess, it'll also be a judge to how the public reacts to self-driving cars. In some ways, it's like Google's very public beta of Glass -- except that no one was going to die if Glass went horribly wrong. Consumers will understandably be a bit nervous the first time they get into one of these vehicles. But with a human being behind the wheel and the cars operating at relatively low speeds around the city, the potential for true disaster seems pretty low.

The 1.3 million people who Uber said die every year in car accidents around the world is a big part of why they're doing this in the first place. The company says 94 percent of those accidents are caused by some variety of human error, and it believes that self-driving cars can see and process more than humans, making them safer. There's a lot to be done before that's a reality, and Uber's definitely starting small. But right now, it has a lead on just about every other company working on self-driving cars.