Second Life's creator is building a 'WordPress for social VR'

Sansar promises to democratize VR development.

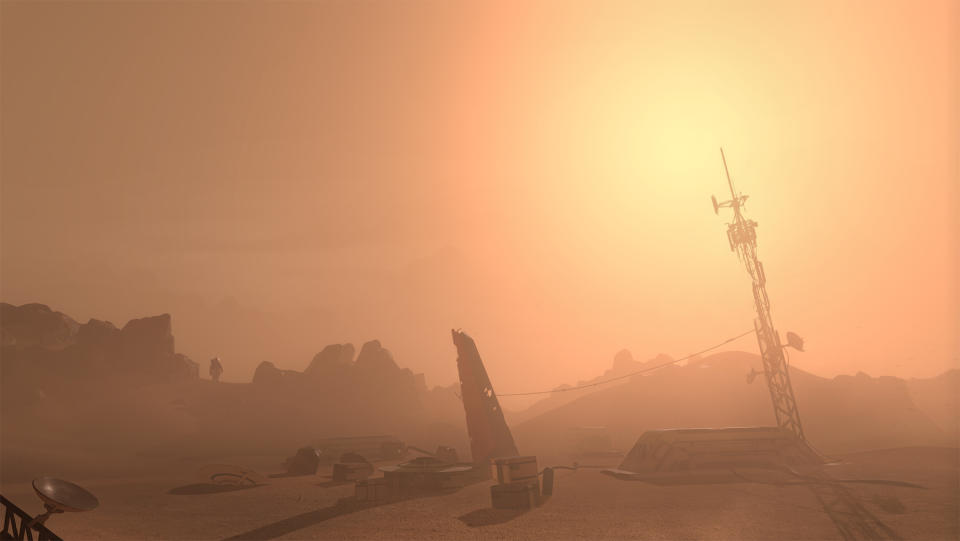

None of this is real. The rocks, the stars, the enormous transmitter standing upright like a needle. It's all a mixture of pixels presented by the Oculus Rift. As I stand on Mars, I urge my senses to surrender to the illusion. I long to be Matt Damon, growing potatoes in a makeshift greenhouse. In reality, I'm standing in a "scene" created by Linden Lab for Sansar, a new virtual-reality platform. A few feet to my left is chief executive Ebbe Altberg, standing in a dinosaur outfit. His avatar waves goofily, breaking my dream within a dream. I can't help but sigh, accepting once more that I'm just a virtual sightseer.

For the last 13 years Linden Lab has been developing Second Life, one of the most popular virtual worlds online. It's easy to scoff at the game, with its dated graphics and simplistic activities. But it's still remarkably popular, averaging 900,000 monthly active users. Part of its appeal is the economy, which allows anyone to buy and sell virtual goods. Talented users can sense what will soon be popular, be it clothes, furniture or vehicles, and make them with 3D modelling software. They're then imported and sold on the in-game marketplace for "Linden Dollars," which can be exchanged for real-world cash. Designers made $60 million this way last year.

Now, Linden Lab is applying the same approach to virtual reality. The latest headsets are packed with potential, but crafting compelling software is expensive. To make a decent VR sandbox, you need a game engine, a team of talented engineers and artists, and people to manage hosting and distribution. That's fine for a large video game developer, but unrealistic for a museum, a charity or a book publisher. With Sansar, Linden Lab hopes to create "a WordPress for social VR." While the company handles the technical aspects, crafty creators are free to build unique assets. Anyone who wants to make their own world can buy these items or import their own, quickly building a shareable and reliable VR experience.

Mars is but one example of what people could make. If NASA or SpaceX wanted to show people the red planet, they might create a world in Sansar. The scene whipped up by Linden Lab is a beautiful, but surprisingly empty playpen. I can't pick up boulders, for instance, or hack away at discarded machinery. Altberg admits that interactivity is "fairly limited" in Sansar right now, but promises to expand it over time. The "scene" we're standing in now was constructed in half a day, he stresses, and is meant to illustrate the platform's flexibility.

A hazy outpost on Mars.

A world on the platform could be small or stretch many kilometers. Teleporters will help you to stitch them together, creating globetrotting tours or history-spanning adventures. Like Second Life, the format is skewed toward social interactions. You could hold a business meeting in VR or show aspiring homeowners around their dream property. You could gather at the lake with some wakeboarding fans or talk about politics in a park. The limitations of a "scene" will be set by its creator, but Altberg expects them to naturally start small. "If you think about how you function socially in everyday life, most of the scenarios you run through are with small groups of people," he said. "Family, three or four people. Coworkers, you might have a meeting with six people."

Altberg hinted, however, that there could one day be public events such as parades and football matches that demand larger groups. "Ultimately, we'll get into the hundreds of avatars that you can have in this place concurrently," he said.

Sansar will facilitate basic games and group play, too.

I feel a tap on my shoulder and take off the Oculus Rift. Peter Gray, senior director of global communications for Linden Lab, is preparing to load another scene for us. In the final version of the game, world switching will be triggered with an "Atlas" search directory. Today, as part of an early demonstration, one of the team's engineers is forced to intervene. I can let it slide, though. After all, I'm standing in London, while Altberg is logged in from the company's offices in San Francisco. A few technical kinks are to be expected. Social VR on its own isn't new, however; I've had similar meetings in AltspaceVR and Hello VR's Metaworld.

As Gray prepares to load an ancient tomb, I ask him about the creation side of the platform. What will developers use to create new assets in Sansar? Pretty much anything, apparently. Right now, Sansar is in what the company calls "Creator Preview." It's effectively a closed alpha, allowing a small group of people to upload items and populate the marketplace. They can use "a variety of third-party tools," Gray says, such as Maya, a 3D modelling tool popular in the video game industry. "We want the experts in 3D content creation to continue using the tools they're already familiar with," he stresses. On a desktop PC, Bjorn Laurin, Linden Lab's VP of product, shows me some software that will allow people to lay out their scenes. It's a simple drag-and-drop interface with a searchable inventory and top-down perspective. I watch as he pulls trees into position and decides where the sun and other important light sources should be.

The "Creator Preview" will ensure lots of assets are ready for the public launch.

"In the future, we'll introduce additional tools aimed at people like you and me," Gray explains. "You'll be able to adjust terrain using voxels, that sort of thing." Before I can quiz him further, I hear my headset connecting to the next scene. I slip the Rift back on, stepping into ... nothingness. Just a blue, empty abyss. Confused, I spin around. Behind me, about 20 meters away, is a large hole. Altberg is standing on the other side and gestures for me to follow. "Come in the door over here," he urges. I point with the Oculus Touch controller and hold down the trigger, an arcing path appearing in front of me. I release the button and watch as my avatar bursts forward. To go beyond the Rift's room-scale tracking, teleportation is a must. I repeat the process a few times, blinking my way across the chasm until I'm standing next to Altberg again.

Immediately, I feel like Indiana Jones. An Egyptian tomb is laid out before me, symbols and torches lining the walls. It feels different than the Mars scene. A little more real. The scene was created using photogrammetry, a technique that combines 360-degree photography and positional data, usually collected through LIDAR (the laser-based equivalent of RADAR.) A research organization and a Paris university collaborated on the project, crunching the data for roughly a day using a supercomputer. A tiny slice made up of 50 million polygons was given to Linden Lab, which crunched it down to 40,000. The project was finally imported into Sansar, creating a scene that anyone can now walk through, examine and touch.

In the real world, there is no public access to this particular tomb. I am, therefore, standing in a place that's normally off limits. Altberg imagines teachers, or tour guides, pointing to the wall paintings and giving out history lessons. Future versions of Sansar will also have interactive elements, including audio triggers, that can hide prerecorded segments. "Over time you'll see more real-world places uploaded into Sansar," he said. "You could visit a vacation spot you're considering and get a feel for it before you go there. Or before you never go there, because it's too expensive or, like this one, there just isn't public access."

Before I leave, Altberg wants to show me one last scene. It's a circular room like the one Professor Xavier uses to access his mutant-seeking device, Cerebro. Instead of a blank wall, an enormous TV screen wraps around us. A three-minute video of a surfer plays on loop, the sounds of the ocean and a dubstep backing track buffeting our earholes. The picture is ridiculously pixelated; the video has been stripped straight from GoPro's YouTube channel, presumably in a low resolution. But it shows what a user's home might look like in Sansar. A personal space, but one that can still facilitate conversation and relaxation.

A home in Sansar could look like anything.

It's unclear how much Sansar will cost for people who want to design their own VR world. Linden Lab envisions a low, monthly fee that will grant creators access to a virtual plot of land. They can build whatever they want on top, and then choose whether to charge an entry fee for visitors. Designers will, of course, also have the option to sell their individual items on the in-game marketplace. Sansar is therefore like a canvas. Linden Lab will provide some basic paintbrushes, but the hope is that artists will bring their own. They'll pay the company to store and display their work -- similar to an art gallery -- and then earn some cash when someone requests a viewing or permission to rework it as part of something new.

"We want to make it so everybody can participate in this medium," Gray says. "You can create your own virtual experience, share it with other people, invite them in, communicate with them naturally and then monetize it, should you wish." A grand vision, but a familiar one. Linden Lab pioneered this model with Second Life, pushing its users to build new content for the rest of the community. Sansar is just the next step -- a Second Second Life, or Third Life if you will. The difference this time, of course, is the entry fee. Almost anyone with an internet connection can access Second Life, while Sansar requires a high-end headset to be fully appreciated. It could make the platform a quiet, desolate place at first.