Researchers figure out trick to a fruit fly's acrobatic flight

The tiny insects are surprisingly buff.

If you've ever tried to swat a fruit fly out of the air, you know how crafty the little buggers can be at avoiding your swings. Turns out that not only are they incredibly agile, they're super efficient as well, using only 12 muscles (each controlled by a single neuron) to propel itself through the air. And, thanks to the efforts of a team at CalTech, we know why these flies are so nimble. It's all in the muscles.

Mammalian wings are really just modified arms with skin stretched across. They all still contain shoulder, elbow, wrist and finger joints as well as the associated muscle and neural processing power that such structures require. This is a resource-intensive design, the polar opposite of an insect wing. Their wings are singular structures controlled by a complex "wing hinge" which itself is driven by sets of power and steering muscles.

"Insect power muscles are the most powerful muscles in any animal on the planet," Thad Lindsay, a CalTech postdoc and first author of the study, said in a statement. "However, this means that they are ill-suited to actually control wing movement precisely. That's where the tiny steering muscles come in." There are two kinds of steering muscles: tonic muscles, which serve as the continuous fine motor control for each wing, and phasic muscles, which only kick in when the fly needs to make a hard turn or other powerful course correction.

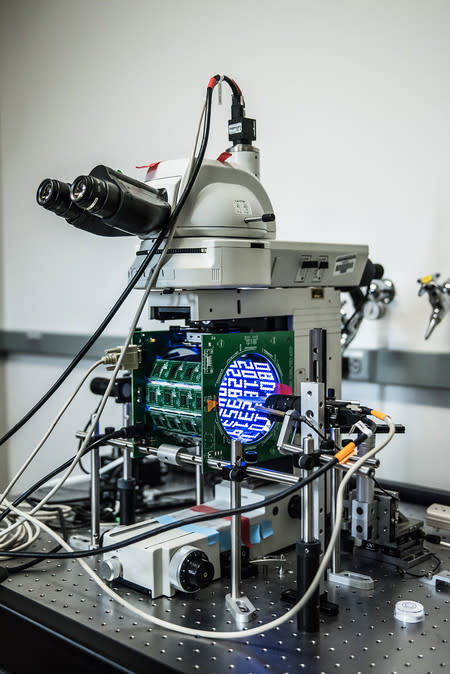

To understand precisely how these muscles worked together, the CalTech team bred a race of fly that produced a glowing protein whenever calcium was present. The flies use calcium to initiate muscle contractions so the stronger the contraction, the brighter the glow. Then the team hooked up these flies to a -- I kid you not -- "fruit-fly flight simulator" which displays different visual cues that instigate the fly to change course. By studying how much, and in which combination, the flies' muscles lit up, the team managed to suss out how their charges so deftly manage to avoid mid-air collisions. And now that they understand how simplistic flies do it, the team hopes their research will help explain how more complex motor functions developed in more evolved animals.