Ai Weiwei's 'Hansel & Gretel' is a surveillance playground

The installation mirrors how we trade privacy for entertainment.

Should you Instagram an art exhibit?

Taking an art selfie might mean participating in the aesthetic experience, hacking and remixing it with your presence. Then again, maybe commoditizing the affair for likes detracts from art's ability to make us slow down and be immersed in something outside ourselves.

At Hansel & Gretel, an interactive installation about modern surveillance by Ai Weiwei, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, selfies are part of the experience.

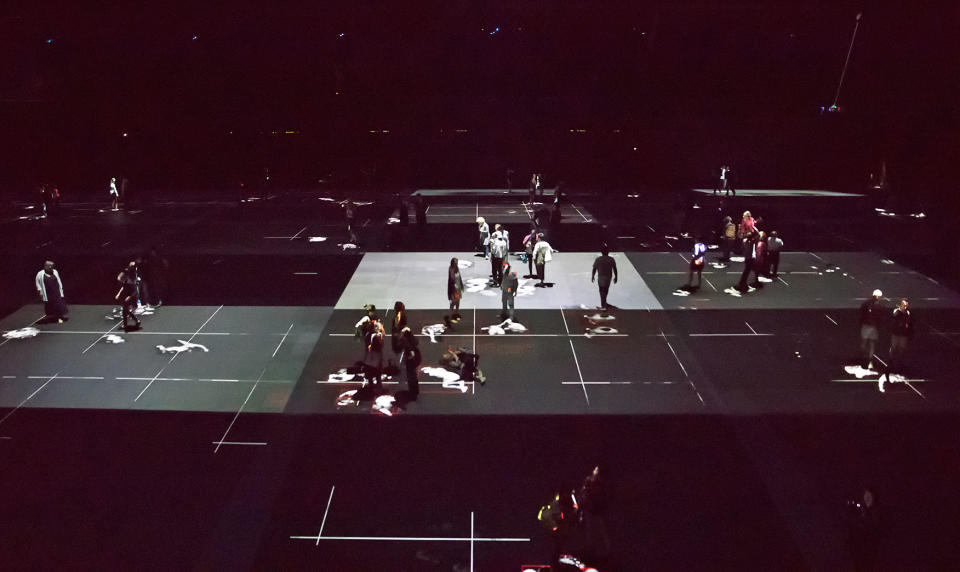

The installation begins in a 55,000-square-foot dystopian playground. Set within New York's Park Avenue Armory, the hall is cool, dark and quiet, giving the illusion of privacy. But everyone who enters is tracked relentlessly from above by 56 computers with infrared cameras, projecting bird's-eye images of visitors onto the ground next to them, outlined with red boxes. Start walking and these ghostly portraits remain, leaving a digital trail. The spying feels aggressive when whirring drones survey the area, but they're just a distraction when everyone is already being tracked in silent, subtle ways without escape.

Yet people are overwhelmingly having fun. They spin around, strike ballet poses and make snow angels on the ground, then whip out smartphones to capture the imprint.

The more fun you want to have, the more you have to step into the light.

The floor is lighter in several areas, which create more snapshots of your movements. People gravitate toward them. The more fun you want to have, the more you have to step into the light.

The juxtaposition of an imposing environment with carefree enjoyment is disconcerting but understandable. While visitors share the pervasive feeling of being watched, they don't know who's watching, or to what ends. It's hard to care. Besides, everyone else is consenting to being monitored too, and look at the fun they're having.

This is the heart of the installation: how we trade our privacy for fun.

"We also are actively involved in this," said Jacques Herzog on a panel at the installation's opening. "It's not just that we are victims."

Every time we use services like Instagram or Snapchat, we voluntarily give up our data in exchange for entertainment. The more we give -- adding geolocation, tagging friends, linking other social media accounts -- the more we're rewarded with interesting features.

Sometimes the nefarious ways our data is used comes to light -- advertisers used to be able to exclude Facebook users on "ethnic affinity," and Uber bought anonymized Lyft receipts pulled from the email inboxes of Unroll.me customers. But for the most part, the knowledge of what personal information we're giving up is hazy.

A post shared by Ai Weiwei (@aiww) on June 6, 2017, at 10:18 p.m. PDT

"As a New Yorker, or somebody in the city, you expose yourself to surveillance all the time, no matter where you go," said Ai Weiwei at the panel. "Even if we know there's a camera there, we don't even know what is being recorded and how later [it] would become something which is useful."

Ai knows these issues intimately. While Hansel & Gretel uses surveillance for fun, the iconoclastic artist has also made fun of surveillance. In 2012, while under state monitoring in Beijing, he wryly broadcast four live webcams from his house to weiweicam.com until the government shut it down in less than two days.

While we seldom get a peek behind the panopticon, the second part of Hansel & Gretel provides the viewpoint of the person doing the watching. In a separate area, visitors use iPads to watch feeds from the security cameras, drones and infrared cameras following those in the main hall. They can take a picture of themselves and facial recognition will identify grainy photos of them wandering the building earlier.

"The first part was physically disconcerting -- I couldn't see where I was walking," said Yvonne Caruthers, a fellow visitor. "The second part was alarming."

Yet, like tech companies, the exhibit made public only a sliver of the insights they potentially could have harvested. With all that motion tracking and video footage, perhaps other inferences could be made: who a visitor interacts with, how rapidly they move through the exhibit, which areas they spend the most time in. If the exhibit showed people just how much big data thinks it knows about them, the cost of their earlier fun would be more apparent.

The irony of an installation spotlighting intrusive surveillance is that museums -- like many institutions -- already monitor their visitors via social media.

"A lot of what art institutions are doing is surveilling their population. They're trying to figure out how to get young, hip people to come back to their spaces," said Elizabeth Losh, an associate professor at the College of William and Mary, in Virginia, who studies the relationship between digital and traditional media.

Every hashtag of an installation or museum creates data that curators can use to analyze what features of an exhibition a visitor fixated on and whether those people are social influencers who could attract an even larger audience.

Vast, immersive exhibits like Rain Room encourage the most social media posts and, therefore, the most data. Visitors to Yayoi Kusama's Infinity Mirrors have reportedly waited in line for over three hours, while Wonder, at Washington, DC's Renwick Gallery, brought 732,000 viewers in eight months to an institution whose prior annual attendance was 150,000.

"It has privileged certain kinds of blockbuster shows, certain kinds of optics," said Losh. "For example, there's no way you're going to be able to shoot something selfie-appropriate if you're looking into a microscope at tiny miniatures. It requires certain aesthetic features in order for that combination of the art and social network platforms to work."

Hansel & Gretel has those aesthetics features. The stylized reflections it creates are made for the art selfie, and visitors start snapping because of how they're conditioned to interact with this genre of installation.

The photos that result help to market the exhibition and feed into the data banks of Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter. Ai, Herzog and de Meuron have made an installation with a watchful Big Brother at its center, but it's not because of the ominous drones or cameras. The real monitoring devices are the smartphones we voluntarily point at ourselves. We're creating our own surveillance.