Voting-machine makers are already worried about Defcon

♫•*¨*•.¸¸:*¨¨*: (:-) AAA+++ seller, would hack again (-:) :*¨¨*:.•*¨*•♫♪

Last year, Defcon's Voting Village made headlines for uncovering massive security issues in America's electronic voting machines. Unsurprisingly, voting-machine makers are working to prevent a repeat performance at this year's show.

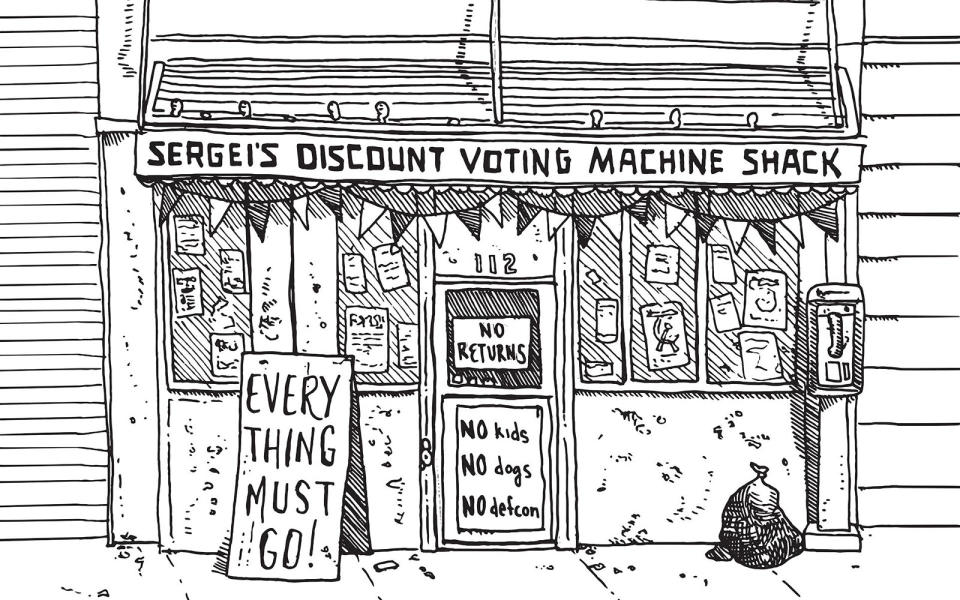

According to Voting Village organizers, they're having a tough time getting their hands on machines for white-hat hackers to test at the next Defcon event in Las Vegas (held in August). That's because voting-machine makers are scrambling to get the machines off eBay and keep them out of the hands of the "good guy" hackers.

Village co-organizer Harri Hursti told attendees at the Shmoocon hacking conference this month they were having a hard time preparing for this year's show, in part because voting machine manufacturers sent threatening letters to eBay resellers. The intimidating missives told auctioneers that selling the machines is illegal -- which is false.

Electronic voting-machine manufacturers -- and anyone with a stake in keeping their flaws secret -- have oodles of reasons to prevent Defcon's Voting Village from having a repeat performance of last year's (perfectly legal) mass hacking of e-vote boxes.

Voting-machine hacking at Defcon isn't new; the conference has been joyfully cracking voting machines since 2004. The problems with voting-machine security, and the industry's unwillingness to acknowledge the problems discovered at Defcon, have ensured the voting machine hacking challenge has been coming back year after year.

In fact, the machines are so badly maintained, notoriously backdoored and easily hacked that even Defcon hackers massively stress out in forums and chat spaces about their own local and federal voting process.

As you'd expect, e-vote machine hacking was more popular than ever last year at Defcon.

But 2017's e-vote hackfest was markedly different because it was officially the first time a large-scale hack of voting machines had occurred (openly, anyway) because the act of hacking them is considered illegal. Not at Defcon's 2017's mass e-vote hack-a-palooza: That was thanks to the hard work of law professor Andrea Matwyshyn. She cleared the way for scores of hackers to legally throw everything they had at voting machines for all to see.

Voting-machine makers with anything to hide couldn't have been happy about that. If you remember the headlines after last year's Defcon, the results that came out of the Voting Village were beyond problematic. Shocking, even.

Defcon's hackers breached every single voting machine in the Village. Some in minutes; many in under an hour-and-a-half. E-vote machines were popped by hackers without insider knowledge and by hackers who didn't even specialize in voting machines.

One attendee remarked on Twitter, "Horrifyingly, some were hacked wirelessly (ie no physical access). Many hadn't had OS or basic software patches in over a decade." They added, "Others had been sold off after use, but hadn't been wiped; still had voter data on them. Didn't hear of any with any credible audit trail."

A journalist at the event tweeted: "One of the Express epollbooks at the Defcon voting machine hacking village had 600,000 voter reg records on it from Shelby County, TN." Voting Village hackers also discovered that all Sequoia brand voting machines shared a common, hard-coded password.

Before the 2016 presidential election in the US, a study released by the Brennan Center called "America's Voting Machines at Risk" stated 43 states were using machines that were over a decade old in 2016. The report's author, Larry Norden, said before the election, "In 14 states, machines will be 15 or more years old."

What's worse, he added that "nearly every state is using some machines that are no longer manufactured, and many election officials struggle to find replacement parts." Before millions of electronic votes were cast for the next US president, Norden told press that "everything from software support, replacement parts and screen calibration were at risk."

So it's no wonder voting machine makers are keen to get their gear off eBay and keep it out of the hands of white-hat hackers equally keen to expose their collective security failings.

The Defcon Voting Village crew seems to be taking it as you'd expect -- like a challenge. Harri Hursti is definitely having trouble, but said it scored at least one machine from "an e-cycling company [that] had bought 1,300 voting machines, which it acquired when the ceiling of the warehouse in which they were being stored collapsed."

Hursti told press, "We found the company had already sold 400 of the machines, in some cases back to counties for voting duties."

So, you know. This is fine.