How Dandelion is making geothermal heating affordable

The Alphabet spin-out is offering systems in New York with no upfront fee.

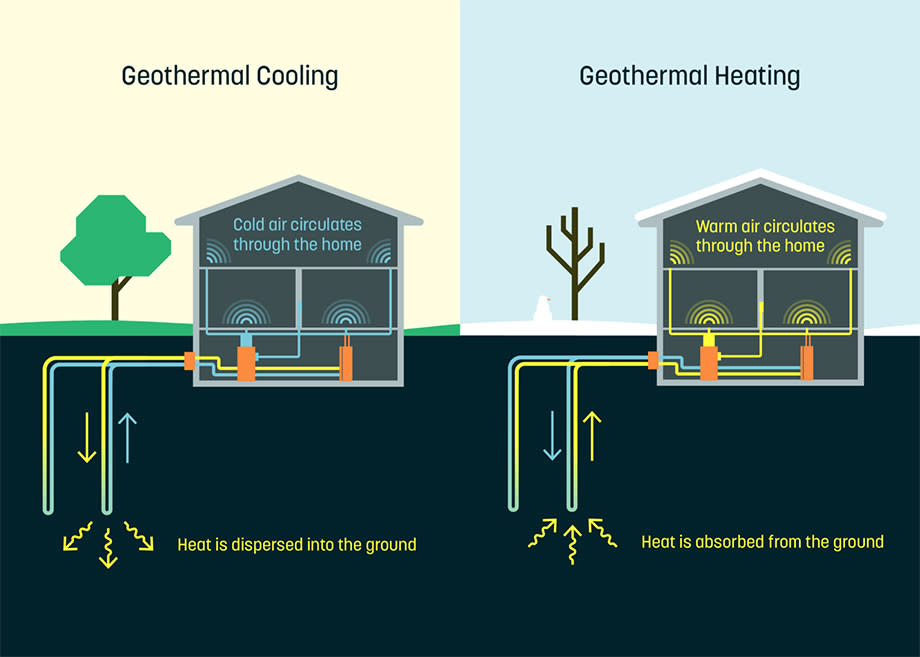

Millions of US citizens still use oil and natural gas to heat their homes during the winter. Many would like to switch to geothermal, a cleaner and ultimately cheaper system that leverages the natural temperature of the earth. A few feet below the surface, the soil sits at a reliable 50- to 60-degree Fahrenheit all year round. Pipes known as 'ground loops' push round a special antifreeze solution that absorbs this constant temperature in winter and disperses unwanted warmth in the summer. A large indoor heat pump uses the mixture to boil a refrigerant fluid; the resulting gas is then compressed to higher temperatures and distributed around the home.

Installing the necessary equipment is expensive, however. Dandelion, a company that started inside Alphabet's X division, is trying to make geothermal cheaper and easier to install. While not the most eye-catching technology, especially compared to electric cars and sea-cooled data centers, it's arguably one of the most important for the environment.

A typical geothermal system costs between $10,000 and $40,000 to install, depending on the size of your home, the makeup of the soil in your yard and whether you have ductwork for the heat pump to attach to. Dandelion's system, meanwhile, will set you back $10,994 to $19,744 after relevant tax credits and incentives. Alternatively, you can pay nothing upfront and spend $79 to $137 per month over 20 years. The latter is unusual and highly attractive because it allows cash-strapped homeowners to install a system and start saving on their utility bills straight away.

There's a trade-off, though: flexibility. Most companies will send an engineer to assess your home and design a bespoke or highly customized system. Dandelion, meanwhile, has a fairly standardized product. "We designed a [geothermal heating] system that works for most homes," Kathy Hannun, chief executive and co-founder of Dandelion explains. "And a home can either qualify for it or not. If a [customer] qualifies, then they qualify for a very standardized product that will work well in their home."

The startup has developed its own geothermal heat pump, too, called Dandelion Air. It was built in partnership with AAON, a specialist manufacturer of HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) systems, and comes in four different sizes. According to Hannun, Dandelion is able to make and sell the pump at "a fraction of the cost of what has been available on the market before," which contributes to its aggressive pricing plans. Unlike most heat pumps, many of the parts come pre-assembled. The exterior is also made of aluminum, rather than steel, so it's easier to carry down stairs.

"It's better than something that was just so, so bad already."

Dandelion Air units are fitted with "state-of-the-art monitoring and controls," Hannun said, that check the system for problems. These are critical because Dandelion relies on regional companies such as Aztech Geothermal and Lake Country Geothermal to drill the holes and install some of its residential systems. The first time the pump is turned on, it runs through a self-check 'commissioning sequence.' Dandelion can then monitor the system remotely and intervene if there's a problem, maintaining quality and customer trust in the underlying technology.

Households can access their data to see how much they're spending, and Dandelion surveys its customers to determine how much, on average, they save by switching to geothermal heating. "Having that real data will just, I think, lend a tremendous amount of credibility to an industry that hasn't had that much credibility in the past," Hannun explained. "It's definitely an investment, but it's one that's well worth it."

These improvements are welcome and long overdue in the industry. As Forrest Meggers, an assistant professor in the School of Architecture and the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment at Princeton University, explains: "It's better than something that was just so, so bad already. That's really it. The HVAC industry is just the slowest moving."

Hannun's career, though, has been anything but slow. She studied civil engineering at Stanford University and then spent a year working on hydroelectric projects in the Philippines and water quality monitoring in Mexico. In early 2010, she took an entry-level position at Google and re-enrolled at Stanford for a master's degree in theoretical computer science. That led to a marketing role at X, which was originally called Google [X], inside the company. "At that time, X was very much in stealth mode," she explained, "so all of my friends made fun of me and said I had the easiest job in the world because I was doing marketing for a part of the company that did no marketing."

Her role quickly evolved into a "little bit of everything," or whatever the team needed help with. She worked on the launch of Google Glass and Project Loon, a network of high-altitude balloons that can provide internet access. Hannun extended the company's work by helping scientists access data, captured by the balloons, about a layer of the stratosphere that is typically hard to analyze. "It was a huge opportunity for atmospheric scientists to get this data so that they could improve climate models and just do research on it," she said.

"The scale of the saving was immense, and staggering."

Afterward, Hannun worked on a project called Foghorn, which investigated whether seawater could be turned into a replacement fuel for gas-guzzling cars and trucks. The project was eventually shut down, and Hannun was approached by Bob Wyman, a Googler based in New York, to look at geothermal heating instead. "I didn't really know what it was," Hannun admits. "So it triggered a lot of research. I had to get to know it and understand the barriers and the potential."

X, now a division under Google's parent company, Alphabet, looked at how much people were spending on heating and cooling in the US, as well as the potential savings if they switched to geothermal heating. "The scale of the saving was immense," Hannun said. "And staggering."

The large upfront fees were a problem, though. The team realized that the ground loop drilling was the biggest cost and, therefore, the greatest opportunity for technological innovation. These holes are typically dug out by large, intrusive drills designed for water wells over 1,000 feet deep. Most ground loops, though, only need to descend a few hundred feet. X prototyped a number of ambitious alternatives including a high-pressure water jet, a modified jackhammer that could worm its way underground and the use of liquid nitrogen to create frozen and easily chippable soil. Eventually, it found a solution that was smaller, faster and cheaper.

X is meant for projects that require huge amounts of expensive research before they can be commercially successful. The technology was incomplete, but the team knew it could leave the safety of Alphabet and still thrive with its standardized product and improved heat pump. The drill was clearly important, but Hannun knew it could be developed alongside the rest of the business. She was also aware that the team would learn and iterate faster by completing systems in the real world.

"Geothermal is already a product that you can install. What we're doing is just improving it, making it better and less expensive," Hannun said. "But that is a process best done by iterating in the real world and getting things done. Seeing how it goes, improving, refining, testing. All of those things just require steady progress over time with some of these larger step changes, like with the drilling technology or the Dandelion Air."

In July 2017, Dandelion's so-called 'graduation' from X was official. "We just decided mutually with X to spin it out because it seemed like the type of business that could survive on its own," Hannun said. "One that would benefit from a more startup mentality."

"We just decided mutually with X to spin it out."

The drill is still a bit of a mystery. According to Hannun, the custom machinery has a vibrating head that causes the soil to act more like a liquid. It makes the ground easier to cut through and also accelerates the installation of supportive casing for the ground loops. "Our Dandelion drill is specifically designed for the residential geothermal use case," she explained. "It's much faster at putting in loops. It creates a lot less disturbance in the yard. And because it's faster, you don't have to pay for as much remediation for the yard and [garden] spoils removal."

Dandelion completed a "few dozen" systems last year. Of these, a few were installed with the company's own drill, Hannun said. The company is aiming for installations in the "low hundreds" this year and will use its bespoke machinery for "quite a few [homes] this fall," she said.

The geothermal community is optimistic about Dandelion's drill. Rosalind Archer, head of the engineering science department at the University of Auckland, as well as the Mercury Chair in Geothermal Reservoir Engineering and the Director of the Geothermal Institute, told Engadget: "My gut says it sounds like a seriously good idea."

Forrest Meggers said the company was being "very strategic" by "addressing such a critical component." He was skeptical, though, about the drill's ability to tackle layers of "bad rock," which can surprise drillers beneath the soil. "There are challenges, I think, that remain to be solved," he said. "And they're probably working toward them."

"There are challenges that remain to be solved."

Dandelion is starting small. The company has just 17 employees, with one half in the field and the other handling software development, mechanical engineering, marketing, customer support and more out of its New-York office. The east-coast location is perfect because, at least right now, Dandelion only operates in parts of New York state, including Hudson Valley, Capital District, Niagara Falls and the greater Rochester area. The company footprint is small compared to many startups with world-dominating aspirations. But, of course, few of those businesses are trying to dig up people's backyards and install sophisticated heating systems.

Over two million homes in New York still use heating oil, so it'll be a while before Dandelion saturates the market and needs to look elsewhere for customers. The Alphabet spin-out also qualifies for valuable tax credits in the state, such as the federal Residential Renewable Energy Tax Credit, which takes 30 percent off the installation price, and the New York Ground Source Heat Pump Rebate initiative, which offers a rebate of $1,500 per ton of cooling capacity (the largest Dandelion Air is five tons).

Together, these incentives can lower the cost of a geothermal heating system by over 45 percent. On its website, Dandelion claims that a $36,725 system will run you $18,433 instead. "Dandelion spun out at the right time to take advantage of the tax credits," Meggers said. "But they also claim they don't need them. I think they can only say they don't need them if they actually achieve the [drilling] innovations they want to do."

The company isn't in a rush to expand. Hannun said the team wants to optimize its pump, software and financing before moving into markets beyond New York state. "We want to figure out all the initial pieces and put them together and make the process really hum," she explained.

Dandelion's system, for instance, requires customers to own or install ductwork in their homes. The company is quietly working on a product called Radiate that will, as its name suggests, support buildings with baseboard radiators and underfloor heating systems, too. "Air is literally the worst medium you can use to heat and cool anything," Meggers said.

The startup is also considering different approaches to ground loop installation. Last December, Rhinebeck's Mayor Gary Bassett announced his interest in a 'right of way' model that would allow Dandelion to install and own a widespread system of ground loop pipes. Residents would then have the option to connect their home and switch away from expensive fuel oil or propane. The mass installation would be cheaper for Dandelion and also set the company up as a sort-of energy provider for the area.

"A geothermal system for a [residential] block would make much more sense," Meggers said. "In that case, it would be a large rethinking of the service model. You would have engineers running the system and basically selling heating and cooling in microgrids."

If Dandelion can perfect these ideas, it could have a huge impact on the energy market in the US. For now, though, the company is happy to focus on the east coast and improve rural living home by home. "New York alone is such a huge market that even if we just focused here it would take us years and years and years to even start to address it," Hannun said. "That's not to say that we won't expand sooner. It's just we don't have to. I think that just gives us the freedom to do what's right for the business."