'Red Dead Redemption 2': Separation of crunch and art

Hands-on with Rockstar's cinematic cowboy game amid a crunch controversy.

Four days before the debut of Red Dead Redemption 2, arguably the most high-profile video game launch of the year, the non-profit organization Take This sent out an email to its supporters and the media.

"Crunch is yet again a hot topic in the gaming news," it began. "With the recent stories about crunch development there has been a renewed interest in Take This' 2016 white paper on crunch and many organizations have come to us for comment on the topic."

That white paper is one of the only academic examinations of video game crunch — what it's called when developers work significantly more than 40 hours a week to complete a project on time. It's a pervasive, divisive factor in the industry and one of the top rallying cries for those who want to unionize game development in the United States. Crunch, according to Take This, negatively affects productivity, brain functions and mental health of employees and their families, increasing burnout and turnover.

Crunch is in the news right now because of a single sentence proudly uttered by Rockstar Games co-founder Dan Houser and quoted in an October 14th Vulture article about the creation of Red Dead Redemption 2: "We were working 100-hour weeks."

The fuse was immediately lit. Developers and critics pounced on Rockstar, denouncing crunch as a practice, while some former employees shared horror stories about working at the studio, saying crunch was not only accepted, but expected, and it had been for years. Developers described getting to the office at 9 in the morning and not leaving until 10 or 11, seven days a week for weeks at a time. They outlined a pattern of mandatory unpaid overtime practices, and many described losing friends, family and their own mental stability during these times.

"I was pushed further into depression and anxiety than I had ever been while I worked there," a former Red Dead Redemption 2 developer told Kotaku. "My body was exhausted, I did not feel as though I was able to have any friends outside of work, I felt like I was going insane for much of my time there and I started drinking heavily."

The crunch spotlight

Rockstar is one of the largest video game studios in the world. Founded in 1998 as a subsidiary of Take-Two Interactive, Rockstar is responsible for the most lucrative game in history, Grand Theft Auto V, and a lineup of other successful AAA franchises including Red Dead and Max Payne. It has eight offices across the US, England, Scotland, Canada and India, and thousands of employees.

Rockstar co-founders (and brothers) Dan and Sam Houser have a reputation for seeking perfection — a strategy that has paid off handsomely over the years. In 2012, Dan Houser bought the Brooklyn mansion where Truman Capote wrote Breakfast at Tiffany's for $12.5 million, setting a monetary record for the city. In 2014, former Rockstar North President and head of the Grand Theft Auto series Leslie Benzies spent £500,000 to preserve a church in Scotland. The Housers had a combined net worth of £90 million in 2014.

Meanwhile, Grand Theft Auto V, which came out in 2012, continues to bolster Take-Two's bottom line. When the company reported having more than $1.4 billion in cash and short-term investments in its 2018 fiscal year report, it noted, "We achieved these results despite an unusually light release schedule, reflecting the strength of our robust catalog led by Grand Theft Auto."

Rockstar is an effective and profitable studio. However, that success has been irrevocably tied to extreme crunch, and not just recently. In 2010, during development of Red Dead Redemption, an open letter purportedly written by wives of Rockstar San Diego employees detailed a distorted work-life balance required by the studio. They threatened legal action if conditions didn't improve. Rockstar waved off the letter, and Red Dead Redemption came out later that year to fantastic sales and acclaim.

In regard to recent claims of extreme crunch, a number of current and former Rockstar employees have spoken up in support of the company. They don't deny working overtime, but they say it's worthwhile and not excessive, especially when they get to create such high-end experiences. Other employees argue this attitude contributes to the problem, creating situations where they feel pressured by everyone around them to work longer hours.

The issue is bigger than Rockstar, though. Crunch has long been an accepted fact of the video game industry, and it first took center stage in 2004 with the publication of the "EA Spouse" blog post, a letter sharply criticizing the labor practices at Electronic Arts. According to the post, employees worked months of "pre-crunch" (eight hours, six days a week), and then "mild crunch" (12 hours, six days a week) and finally crunch (12 hours, seven days a week), with no hope of extra days off or overtime compensation.

"The stress is taking its toll," the letter said. "After a certain number of hours spent working the eyes start to lose focus; after a certain number of weeks with only one day off fatigue starts to accrue and accumulate exponentially. There is a reason why there are two days in a weekend — bad things happen to one's physical, emotional, and mental health if these days are cut short. The team is rapidly beginning to introduce as many flaws as they are removing."

"The team is rapidly beginning to introduce as many flaws as they are removing."

That was 14 years ago. Today, Rockstar is the face of crunch, with developers sharing eerily similar stories about life at the studio. However, the environment for these complaints is vastly different than more than a decade before. Twitter and social media sites make it easy for the narrative to travel, take shape and affect even casual video game fans; there's a growing movement to unionize game development and high-profile cases like Rockstar's are fuel for this particular fire. Video-game critics and fans are more awake to the dangers of crunch and are less willing to accept it as a necessary facet of the industry, at least in its most extreme forms.

Which brings us to Red Dead Redemption 2.

Playing RDR2

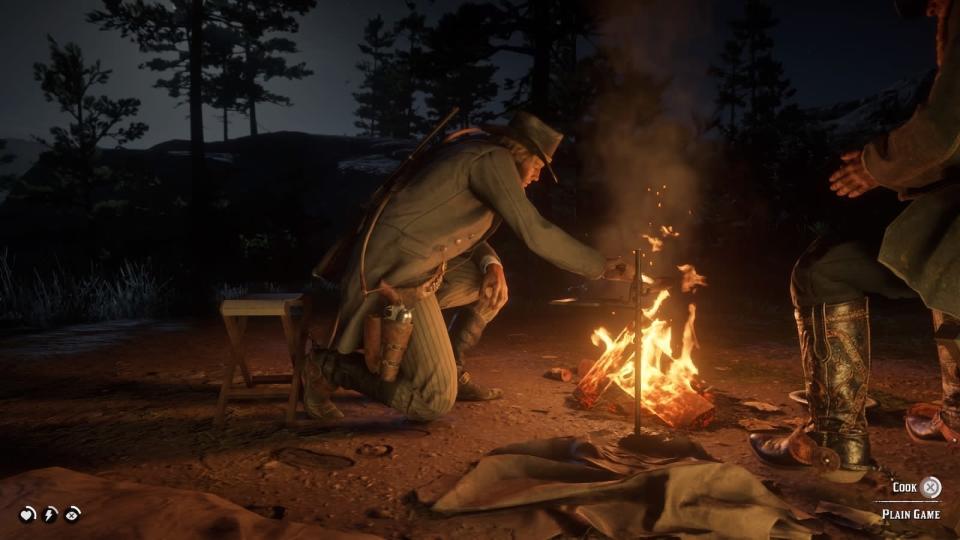

This was the context banging around in my head as I booted up Red Dead Redemption 2 for the first time. Crunch. It wasn't at the forefront of my mind, but it lingered behind every button press as I adjusted my screen's brightness using the Rockstar logo as a guide, and as I watched the impressive introductory scenes light up my living room, complete with credits overlaid in bright red, all-caps type. As the camera panned around characters in cowboy hats and bonnets, the names kept appearing on-screen — art direction, animation, lighting and effects, technical direction, sound design, team leads — and the sheer size of the game hit me full force. It felt like a blockbuster movie already, with drama and interpersonal tension building among this small group of outlaws as they buried their dead and set up camp in a snow-drenched mountain range at the turn of the 20th century.

Red Dead Redemption 2 plays like you've been dropped into the second season of an Old West Netflix series directed by Quentin Tarantino and produced by the Coen brothers. It's incredibly polished and rich, and the obsession with detail is clear, each scene making the game world and characters leap off the screen.

Red Dead Redemption 2 places an emphasis on cinematic scenes, slow-burning dialogue and dramatic musical cues, all centered on the cowboy gang of Dutch Van der Linde and the main playable character, Arthur Morgan. It's a prequel, fleshing out stories that were only hinted at in Red Dead Redemption eight years ago.

Arthur is a classic Cool Cowboy — witty, gritty and wise (and good with a gun, of course). He grew up in the Van der Linde gang and believes whole-heartedly in Dutch's plans. As the group of cowboys, cooks and women journey across the US in rickety wagons, Arthur's loyalty is tested again and again.

Traveling is a critical aspect of Red Dead Redemption 2. The game world is huge and packed with animals, rugged American landscapes and Old West towns to explore. Rockstar has hesitated to call it an open-world game, and with good reason — while the lands are vast, they're locked out of play depending on which mission is active. While there is some wiggle room to explore specific areas, Arthur can't simply wander the Old West whenever he wishes. In some instances, ditching the main path actually ends the game, prompting players to try again from the last checkpoint.

Much of the narrative unravels while Arthur is on horseback, careening through fields and forests while hunting or tracking enemies. The gang talks as they ride, dropping information about previous hits, filling in gaps and gossiping about other members. This dialogue is crucial to understanding the gang and the broader narrative of cowboy-era bureaucracy, and developers have made it as easy to follow as possible.

While riding, players can keep pace with the group's leader by holding down a single button, tapping it to speed up. There's little need to even keep Arthur's horse on any particular path, as it'll mirror the leader's movements, as well. It seems clear that Red Dead Redemption 2 was designed with story in mind, and many interactions in the game are streamlined in a similar fashion to let the narrative shine.

There are moments when the pieces all come together and Red Dead Redemption 2 is an impressive piece of art. Long horse rides often transition into cinematic scenes — the music swells as the sun shines over the Van der Linde gang's dusty caravan. Black bars close in on the top and bottom of the screen, and the camera shifts and zooms dramatically.

Crunch.

That's when I remember those black bars were an afterthought, only added to the game in the past year — a decision that heaped extra nights and weekends onto some developers' packed plates.

While I admire these in-game moments, they're also the ones that shake me out of Red Dead Redemption 2's spell the most abruptly. The more beautiful the scene, the more obvious how much talent and work has gone into it, the more I think about the people behind it and how many 80-hour weeks they might have endured; how their emotional and physical health must have fared; how many family milestones they may have missed. The more I think about crunch.

Red Dead Redemption 2 is a gorgeous, high-quality game that developers should be proud of. It's an incredibly impressive effort that, over eight years, included writing 500,000 lines of dialogue, scoring 192 pieces of music for interactive scenes, spending 2,200 days in the motion capture studio with 1,200 actors, and coding more than 300,000 animations. Meeting, building, testing and editing, again and again, eight years over, at times for 80 hours a week.

More players should be forced to think about the people making their games, from individual developers in the indie scene to thousand-strong teams in the AAA realm — Rockstar's realm. The Red Dead Redemption 2 crew built a cinematic beast of all-American glory and gunfire, and stories about crunch won't change this fact. However, talking about crunch can change how games like this are made. In fact, they can help make these games even better.

How the West was rested

The 2017 International Game Developers Association Survey polled 963 video game creators from around the globe, and 53 percent said crunch time was expected at their job, while 43 percent said they'd experienced crunch more than twice in the past two years.

"Crunch has so many harmful effects on workers' mental health," Take This ambassador Eve Crevoshay said this week, in light of the Red Dead Redemption 2 allegations. "These negative effects can be both short- and long-term, and often coincide with declines in physical health, non-work social connections, productivity, turnover and job satisfaction. Research indicates that productivity declines sharply after as little as four days of extended work hours. Even slight increases over a 40-hour work week are detrimental to hourly productivity after two months."

"Even slight increases over a 40-hour work week are detrimental to hourly productivity."

In August, Rockstar boss Dan Houser described Red Dead Redemption 2 to Vulture as "this seamless, natural-feeling experience in a world that appears real, an interactive homage to the American rural experience. [It's] a vast four-dimensional mosaic in which the fourth dimension is time, in which the world unfolds around you, dependent on what you do."

Houser had a grand, slightly psychedelic vision for Red Dead Redemption 2 and Rockstar developers built it. That's a success. Employees at Rockstar and other major studios are now publicly talking about crunch and discussing ways to improve working conditions for developers. Even Houser is talking about it. That's (the beginning of) a success.