Samsung's LED movie screens deliver more cinematic punch

With extreme brights and deep blacks, don't call it "TV in public."

To the surprise of many, Samsung last year unveiled a cinema LED screen that's ten times brighter than a projector. But it's been hard to actually see one, as they're installed in just a few cinemas around the world. Recently, Samsung demonstrated the screen (now called the Onyx Cinema LED) with the European film lab Éclair in Paris, and I had a chance to get a look at it. With its incredible brights and extreme blacks, the LED movie screen was impressive, but it'll take some work to convince filmmakers, theater owners and movie-goers to adopt it.

Samsung will market three versions, depending on the size of the theater: The 5-meter (19 foot) version I saw will run at DCI 2K (2,048 x 1080), while the 10-meter (34 foot) and 14-meter (50 foot) models will run at DCI 4K (4,096 x 2,160). Those are standard cinema projection sizes, but the screens will support wide or flat DCI and other resolutions with letter-boxing.

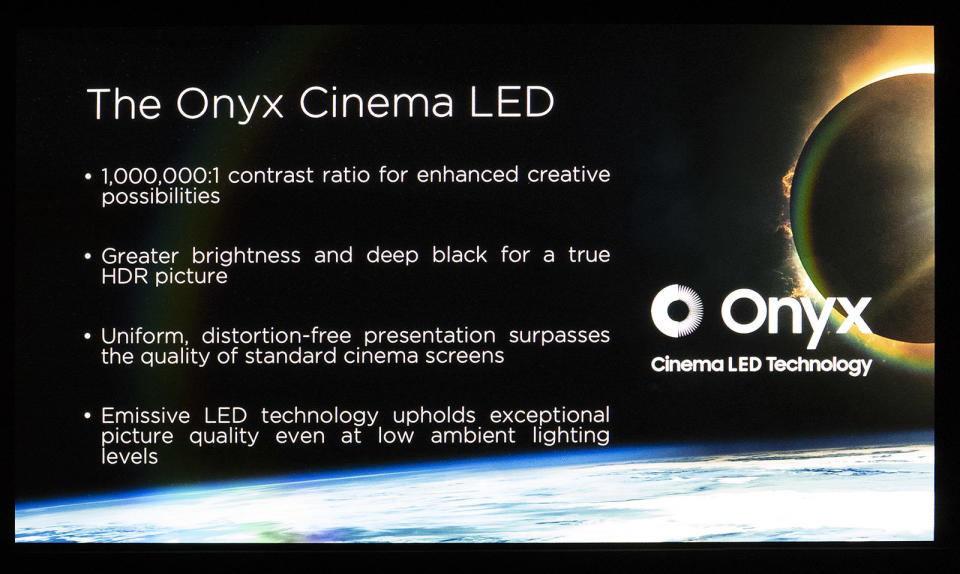

They are also compatible with various flavors of HDR, which enhances the image thanks to a peak brightness of 300 nits, including Samsung's own HDR10+ and Éclair (the latter is what I saw in Paris). "The Samsung Onyx screen is one of the most powerful pieces of equipment that allows us to display HDR content," Éclair General Manager Pascal Mogavero told Engadget.

The screens support 3D technology and should handle it better than projectors because of the higher brightness levels, which can hit 500 nits on the 4K screens. Because of that, the picture will look less muddy and you'll see fewer motion artifacts and blur than with regular projectors.

The Onyx screens aren't gigantic versions of Samsung's QLED TVs, though. Rather, they're based on its outdoor display tech that uses individual SMD (surface mount device) LEDs. Each pixel is self-emitting with no backlight, so you can get true blacks simply by turning off individual LEDs. That's much like how OLED TVs work, and those are beloved by reviewers for their deep blacks.

Samsung essentially puts the sets together by assembling 256 x 360 pixel cabinets, each about 4 feet across. The smallest model uses 24 cabinets while the largest 14-meter version has 178 of them. The specs trounce any TV, with 16 bits of color (trillions) per pixel and contrast ratios that match the million-to-one levels of an OLED set.

One big advantage of the system is that it's fairly easy to replace burned out "pixels" by swapping out the LEDs. You could also presumably update to higher-resolution or other technology by replacing the cabinets. That would surely be a lot more expensive than replacing a projector, however.

Consistency is another key quality. "We have a linear image that's as bright in the center as it is in the edges," said Samsung's Paul Maloney. "Unlike a projection-based system with a lens, if you have a xenon bulb source in the center, the lens curves so the corners of the screen get darker. The same happens with color. The Samsung LED doesn't need to be optically corrected."

On top of that, the Onyx LED emits rather than filters colors, unlike a projector. That means deeper colors can actually be brighter, not darker, generating the high luminance levels needed for true HDR.

The sound, meanwhile, is provided by Samsung's Harman JBL and installed in a special configuration to accommodate the displays. Harman had to essentially redesign everything as speakers can't be placed behind the movie screen like they are now. The Sculpted Surround Sound audio systems are also designed to deliver uniform sound to the more sloped seating arrangements required for the screens.

So how is the image? It's clearly brighter than any projector, and the brightness and contrast are significantly enhanced by the HDR. Samsung and Éclair switched one scene between regular SDR and HDR, and the difference was pretty eye-popping. But films not encoded with HDR certainly won't look bad -- it's only obvious when you compare them side-by-side.

Colors are punchy and looked accurate. Éclair showed off one scene with the famous Michael Bay-style treatment, with orange-hued skin tones standing out against teal-blue backgrounds. Film directors and colorists will be able to optimize color timing for the screens knowing that subtle shadows will still be visible because of the extra brightness.

I hunted for flaws during the projection, and my nitpicks are few. With the relatively low 2K resolution of the 5-meter screen, it was easy to see blocky pixels on text and angled straight lines. That will probably apply to the 4K displays, too, especially up close, since they use the same cabinets. On the whole, though, the effect is not that bad and is no worse than 2K digital projections I've seen. Celluloid film projectors, of course, don't have "pixels," however.

I walked back and forth across the screen, and viewing off-angle makes little-to-no difference in color or brightness perception, thanks again to the individual LEDs. I did notice a bit of blooming in a space scene where an extreme-bright area produced a halo-like artifact against a dark area, but I doubt few moviegoers would notice -- you're not going to be walking around while watching a movie, after all.

My opinion is one thing, but I was curious to know what cinema goers and the filmmakers themselves thought. Many folks still haven't gotten over the transition from celluloid to digital projection, which Quentin Tarantino called "TV in public." Samsung's Onyx system takes that even further, as it's essentially a large, albeit technically superior, TV.

"Some people don't like it because they feel it will change the filmmaker's initial intent," said Mogavero. "If you want to show your movie on a projector, you can still do it. But if you want to completely redesign your movie and think about a completely different way to tell the stories, then you can do that, too. It's widening, not restricting or corrupting the possibilities." Several filmmakers, he said, naming no names, preferred the Onyx image after seeing it next to a double-laser projection.

Onyx might be technically superior in many ways, but Samsung and its partners still need to convince movie theaters to install them. The system is more expensive than any projector; though Kayata noted that the price isn't that far from the fanciest dual-laser projectors. Samsung's argument is that without a projection closet, cinemas can add more seats, and the new tech could draw ticket buyers who might otherwise stay at home. Samsung plans to have 30 locations installed by the end of the year.

Its best argument for the tech, though, might be aimed at viewers who feel the cinema experience is actually inferior to what they can have at home. "The average consumer just loves to enjoy what they're seeing," said Maloney. "We have the likes of Netflix and Amazon doing 4K HDR movies, so these are all things that consumers are used to. All we're trying to do is present that for them in theaters."

Update 11/19/2018 2:31 PM ET: Dolby has told Engadget that the Onyx Cinema LED screens don't support Dolby Vision like the post originally said. It has been updated with the correct information.