We have questions about dual-screen laptops

Usability and engineering issues still need to be resolved.

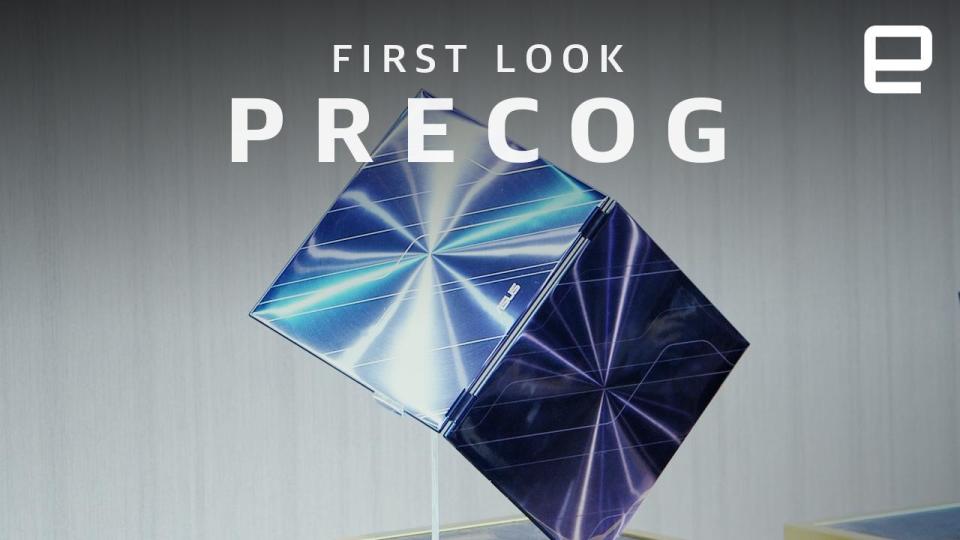

At Computex, ASUS and Intel showed off what they think could be the future of computing: true dual-screen laptops. Open up what's currently called Project Precog, and all you will see are two panes of glass that can be used in a variety of ways. It's a laptop! It's a dual-screen desktop! It's a lay-flat tabletop machine for board games! And that's not all, because you can use it in tent mode to show two things off to two people at once. No company wants to go into too much detail as to what a concept device really is or how exactly it works. An idea that is shown off at a trade show in June of 2018 may have little resemblance to the hardware that goes on sale 12 months later. At first blush, Project Precog looks like it could be the start of a new frontier for personal computing. But, the truth is that this been tried before, and it's not clear what's meant to have changed in the last seven or eight years. So here are the questions we have about this next wave of dual-screen laptops. Generally speaking, laptops are designed in two distinct parts. There's a base that houses the logic board, IO, batteries and the interface, and the significantly thinner top half with the touchscreen/display and, often, a webcam. Part of this is out of necessity, because components, batteries, interface ports and keyboards all take up space. Even the thinnest ultrathin laptops on the market are limited by the laws of physics. The exception that (kinda) proves this rule is Microsoft's Surface Book, which works both as a tablet and a laptop. In that instance, the display/tablet portion houses the bulk of the machine, as well as a small battery, the cameras and a 3.5mm headphone jack. But it's also running with compromised performance unless you connect it, via its fulcrum hinge, to the bigger battery, IO and external GPU in the base. ASUS's Project Precog demo showed the device laying flat and being used as a quasi-futuristic gaming device. Judging by eye at the event -- we weren't allowed to touch the so-called prototypes -- it looked as if both halves were the same height and stood about 0.6cm tall. That means that it would be about 1.2cm closed, making it the same rough thickness as a gaming laptop like Razer's Blade 15. How much of that real estate is taken up by duplicated components like display controllers? Will both halves need their own dedicated logic boards to avoid overtaxing the primary system? Or will one side play host to a battery while the other holds all of the other components? And speaking of which... No two people use a laptop battery in the same way, so it would be hard to talk about battery life as an absolute. It's fair to say that a decent productivity-focused laptop would be expected to last a full working day on a charge. That would include, say, running Office apps, some light browsing and maybe some music and video. And that's with one display: adding a second would reduce that significantly, which is a problem for people on the go. The solution to this may be in the form of Intel's Low Power Display Technology (LPDT), which does what its name implies. At Computex, the company claimed it could build a screen that used half the power of an existing model. Intel's Gregory Bryant even claimed that a Dell laptop that was retrofitted with the new display looped video for 25 hours straight. It's not a verifiable claim, and we don't know if Intel juiced the result by, for instance, dimming the backlight to make the screen unusable in all but the darkest rooms. Then again, let's give it the benefit of the doubt: If this technology is as good as it claims, then it might be enough to woo back folks who are scared a dual-display laptop won't last for long on the road. Dual-screen laptops, where the keyboard and trackpad have been replaced by a secondary display, are hardly a groundbreaking idea. Back in 2011, Acer released a laptop with two 14-inch displays, the Iconia 6120. The fact you didn't remember it says a lot about how well the machine fared. In his review, PC World's Jason Cross said he found himself "typing more slowly and making more serious errors than I would on a good physical keyboard." He added that the extra hardware necessary to accommodate the second display "makes the system thick." It also crowded out other pieces of gear considered essential in 2011, like a card reader, Bluetooth, and a USB/eSATA port. Not to mention that the battery lasted an embarrassingly short 2 hours 11 minutes when unmoored from a wall socket. CNET's Dan Ackerman said the device failed to answer the question "Why would anyone need a dual-touch-screen laptop?" And he agreed on the point that a dual-screen laptop will "never be as intuitive as typing on a physical keyboard." Although later "with a little practice," he adds "we found it to be as easy as an iPad keyboard, which is to say that it works for basic interactions and writing blocks of text up to about 500 words." Both reviews also criticized the smallness of the virtual touchpad that sits beneath the virtual keyboard. A year previously, Toshiba launched the Libretto W105, a 7-inch laptop that attempted the same job. The device was a limited-edition treat for fans of the company, which was celebrating 25 years in the laptop business. Joanna Stern's review for Engadget describes the keyboard as "fairly cramped," making it easy to mistype. Bad software that isn't designed for the dual displays, poor performance and a really bad thermal design didn't help. And, again, the machine lasted for just over two hours on a charge, making it pretty pointless, too. (We could talk about Sony's Tablet P, too, but that was never seriously intended to operate as a productivity machine.) Right now, it's hard to see what a dual-screen laptop would do better than a laptop or tablet in specific circumstances. One of the things that appear to have stymied the rise of tablets as productivity machines is the fact that all-glass keyboards aren't great. Two thumbs on a smartphone is fine for hammering out short messages, but a whole essay? We're not so sure. The biggest sign that people haven't taken to using a software keyboard as a productivity tool has been demonstrated by Microsoft and Apple. Both companies pushed generously-proportioned tablets and said they were the future of work. And when both launched Pro versions of those machines, they developed portable, laptop-esque keyboards to go alongside. If these companies realized, or were told, that people needed real buttons, then what hope for Precog? Now, these questions aren't intended to suggest that ASUS, Intel and the others who join this bandwagon are wrong. After all, there were plenty of people holding their noses in mock disgust when the iPhone made touchscreens de rigeur. "Try typing a web key on a screen on an iPhone. That's a real challenge. You can't see what you type," said Jim Balsillie in 2007. A decade later, and phones with physical keyboards are little more than a curio for folks who don't want to leave them behind. And, certainly, given BlackBerry's fortunes, history appears to have been on the side of the screen. Who knows, maybe Precog will offer us so many new ways to work that we'll slap ourselves for not having seen it at the time. And, personally, I'm into the idea of using Precog as a portable, dual-screen desktop that I can take between desks (so long as there's a power outlet nearby). I'll just bring my own keyboard and mouse along for the ride.