Facebook's 'the future is private' mantra doesn't exonerate it

Maybe the private should've been part of the past and the present too.

On Tuesday, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg took the stage at F8 -- the company's annual developer conference -- and made the case for a pivot to a more privacy-focused social network. Core to this idea is a phrase that was displayed on the screen in large, bold letters: "The future is private." According to Zuckerberg, "personal" conversations make up the fastest areas of growth in online communication. "Privacy gives us the freedom to be ourselves," he said. "We need the intimacy more than ever. That's why I believe the future is private."

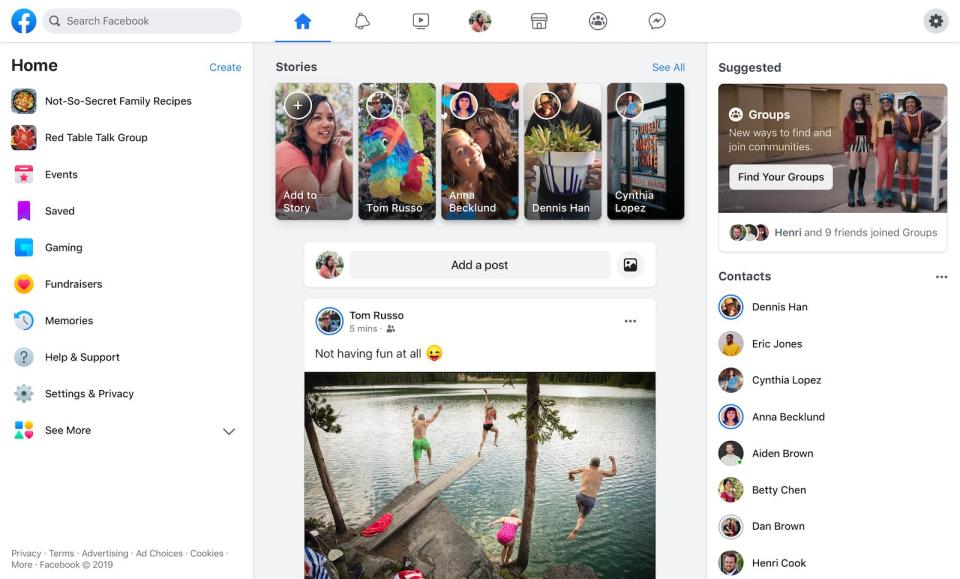

Except, the idea around privacy is not futuristic, or even new. Many of Facebook's efforts in this arena aren't novel in the slightest. The company often touts ephemeral messaging, for example, as a way it's committed to a private and intimate experience. But the notion of temporary stories came from Snapchat, which debuted way back in 2011. It wasn't until August 2016 that Instagram introduced its own take on the concept with Instagram Stories, a whole five years after Snapchat was born. Thanks in part to Facebook's clout, the feature proved to be a hit, and the company eventually integrated it in pretty much every other Facebook app.

Facebook also announced that Messenger will finally have end-to-end encryption by default. Not only does WhatsApp, Facebook's other messaging product, already have this feature, but several others have also made privacy a core selling point. Signal, a favorite among cybersecurity experts for years, encrypts all of your messages and stores very little of your metadata. It's also difficult for a stranger or spammer to contact you if they don't know your number. Facebook, on the other hand, will let anyone with a profile send you a message unless you specify otherwise. Messenger may be end-to-end encrypted, but that doesn't mean it will be free of any privacy problems.

Even the idea of a "privacy-focused social network" is not without predecessors. One of the more obvious examples was Path, an early Facebook rival aimed strictly at close family and friends. It was initially restricted to just 50 friends, which was then increased to 150, before the limit was eventually lifted altogether. Path reached 15 million users at one point, though of course that number was quickly dwarfed by Facebook. It's said that Facebook even "borrowed" some of Path's features such as stickers and reactions.

Basically, closed online communities have existed for years, albeit in a less central space. There are private newsgroups, message boards, Yahoo Groups, and LiveJournal communities just to name a few. Let's not forget that Facebook, too, was a private social network for Ivy League students back in its early days, before the company decided to open its doors to the world. Privacy doesn't just belong in the "future," Facebook, it was there in the past, and in the present as well.

Of course, Zuckerberg didn't always think this way. His statement at this week's F8 is a huge contrast with what he said back at the 2010 Crunchies awards, where he claimed that the age of privacy was in the past. As reported by The Guardian, he said: "People have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people. That social norm is just something that has evolved over time." The interview took place just a few weeks after Facebook flipped a switch that made almost everyone's posts public by default. Clearly, back then, Zuckerberg had a very different view of privacy.

There was a reason for that, of course: more public sharing means more likes, more data and more ads. Facebook says it doesn't sell any of your info to advertisers, but the company still uses your information (based on your profile, shares and likes) to serve you related ads. It wasn't in Facebook's financial interests for you to keep your posts to yourself. One could even argue that the very reason Facebook is as profitable as it is now, is because it managed to exploit users' willingness to be so open about their lives.

That's why it feels more than a little disingenuous that Zuckerberg and Co. have had such a sudden change of heart. It's easy to smile and say that end-to-end encryption, ephemeral messaging and small group sharing will make you "feel safe to be yourself," when that doesn't in any way change the fact that Facebook was careless with the way it handled your data. It's easy to say "the future is private" when the company already spent years collecting data and preying on the blind trust of its users.

Despite Facebook's insistence that the reason it's pivoting to privacy is because of industry trends, the more likely reason is because it has to. It has to persuade the world to move on from the litany of security breaches and data collection scandals that have plagued the company for the better part of two years. Facebook is now synonymous with untrustworthiness, and the company is desperate to change that. "I know we don't have the strongest reputation on privacy right now, to put it lightly," said Zuckerberg on the F8 stage in a terribly unfunny attempt at a joke. Unfortunately for Facebook, the statement "The future is private" falls flat too.