Why do memes suddenly matter in politics?

In 2020, political campaigns have put a lot of effort into memes.

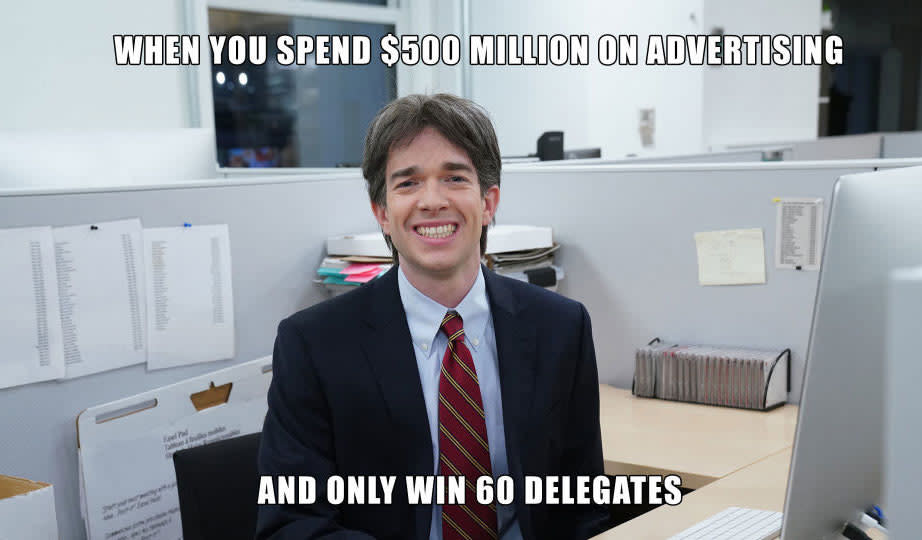

Michael Bloomberg's failed bid to become Democratic Party nominee will go down in infamy. Not only because he bankrolled the whole thing with his own vast fortune, but also where he spent it. Bloomberg's team enlisted figures from Jerry Media, the agency connected to Fyre Festival, where he spent $1 million a day on social campaigns. He even offered minor-ish Instagram stars $150 a pop to support his campaign on the platform. But why? We asked several people connected with politics, memes, and political memes the obvious question.

Social media is typically a poor bellwether for political engagement, and not all voters hang out on Instagram. A TV ad can reach tens of millions of people, but a meme can often reach only a few thousand -- or a couple of million if it resonates. Not to mention that younger audiences, hyper-engaged to the internet, may not be interested in politics per-se. Turnout during Super Tuesday, for instance, skewed far older than the target demographic of a meme campaign.

Matt Charlton is the CEO of ad agency Brothers and Sisters, who previously worked on the London mayoral campaign for Ken Livingstone. He said that Bloomberg's team "thought he had an opportunity [in memes] to make online pop culture," saying that it often drives the news cycle. He added that "if you're launching a brand, and you get a meme going, it helps."

Misha Leybovitch, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and the figure behind Lefty Lenses, a group that previously backed Senator Elizabeth Warren's nomination, agrees. He said that social media is "the well from which everything else springs." And that a good, effective meme "ends up impacting the national conversation, driving the mainstream media."

"Younger generations do not have the attention span to consume traditional political content," said Wesley Donehue. He is a Republican political strategist who ran Marco Rubio's digital campaign in the 2016 primary. "Memes are a great way to both grab their attention and to get a message to them in the two seconds they will give you."

Political operatives expect memes to be an effective campaigning tool, but Charlton feels that there's another cause, here. "A lot of this has been done in desperation, and reflection, to what Trump did in 2016. "Trump owns Twitter," he said, describing the current president as the "Olympic gold medallist of social media." This has prompted, in the CEO's eyes, rival campaigns to find a way of conquering these platforms in response.

"It's a pretty strong correlation between how much you hide your identity and how much of an asshole you are online,"

Charlton said that Trump's tweets aren't tweets so much as "PR ignition points," with a volatile statement getting lots of pickup both from those in favor and against. "It then bleeds into everything else [in the news cycle], and this is how you build and change minds," he added. It's easy to miss the target here, too, and he cited Bloomberg's meatball meme, which became an "embarrassing distraction."

It wasn't just the non-sequitur elements of Bloomberg's campaign that caused it to fail, but the commercial aspect of it. Professor Ari Lightman, an expert in media and advertising at Carnegie Mellon University, said that Bloomberg failed to understand the culture. A paid-for meme campaign was "antithetical to meme-cased culture" because it was "corporate advertising, not the spontaneous, often sarcastic nature associated with viral memes." Essentially, Lightman believes it's difficult to will a meme into existence by decree when so much of it happens at random.

"What makes a good meme," said Donehue, "is something funny enough to grab attention, and on point enough [for you] to remember the message."

Leybovich's group, Lefty Lenses, was previously known as Warren's Meme Team, but has since pivoted to support the Democratic nominee. He said that while memes in the form of image macros are dominated by conservatives, other meme battlegrounds could be more fertile. His area of focus is the sort of What X Are You selfie-lenses popping up on Instagram and Snapchat, which have one big benefit over easily shared images: a lack of anonymity.

"It's a pretty strong correlation between how much you hide your identity and how much of an asshole you are online," said Leybovich. He said that anonymity helps some groups to push and amplify toxic agendas online, hence his focus on filters that you can't game. "The lens format requires your face, you literally can't use it unless your face is in the frame," he said. He added that his work has already been used tens of millions of times with "literally zero misuse."

One issue with memes is that, made by a campaign or not, once they're in the wild, you no longer control them. Charlton said that losing control of your narrative is nearly always bad, "especially on social channels." Professor Lightman said that you risk your words being taken out of context or re-contextualized to say something you didn't intend. And, "with rapid proliferation online," he said, a meme can quickly "become public sentiment." Lightman added that people often take "these snarky, opinionated concepts as facts," without bothering to do the "difficult work of due diligence" to understand what they're looking at.

Biden: Trump better not get in my face... cos I'll drop that motherfucker

Obama: Joe.

Biden: pic.twitter.com/oB6kUbBvuQ— Mollie Goodfellow (@hansmollman) November 10, 2016

Mollie Goodfellow is a British writer and comedian who launched the Biden / Obama memes into public consciousness. The format features an image of Biden and Obama, with a caption of Biden suggesting something childish, with Obama admonishing him. Goodfellow's two tweets garnered more than 120,000 retweets and 200,000 likes and spawned a litany of other posts in the same format.

She said that the comic relationship, with Biden as Obama's "idiot puppy" already existed in the public consciousness. But the first tweet, published the day after the 2016 election, reflected some post-election angst in the public consciousness. "A lot of the feedback I was getting," she said, "was 'oh my God, I really needed this today.'"

Goodfellow said that one downside of the Biden meme was it presented the politician in a positive comic light. As a Briton, she "knew very little about his actual political stances," compared to other politicians. "Now that his policies are being dissected, I don't know that I necessarily agree with a lot of it," she added. "I want to make it clear that [the memes] weren't a tacit endorsement of Biden for president," she said.

Goodfellow, as someone at the center of a meme, believes that the hype surrounding them is often overrated. "I used to argue that it was getting people more involved in politics, but I don't know if that's true anymore," she said. "Even if they weren't necessarily engaged before, it's a shallow form of participation," although she added that, even if it is shallow participation, it's still participation.

It might already be over for the political meme, however. Goodfellow said , more crucially, meme culture is dying, that social media has "become a very shouty, horrible place." And memes have been replaced with shitposting as a more authentic, less competitive form of expression: "Shitposting takes less effort, and is less repeatable. It's very singular, and not repeated by others," she said.

Telling the difference between memes and shitposts is more art than science, and it's often difficult to tell the two apart. The Daily Beast describes shitposts as a "deliberate provocation designed for maximum impact with minimum effort." The lo-fi aesthetic and often controversial (or faux-controversial) subject matter can also help separate them.

Now, Goodfellow feels we should keep politics and meme culture far away from each other. "It's like, what if your dad got into memes and started making memes? It feels very inauthentic at a time when people are really valuing their authenticity. It's amazing how often people are 'We need to make something viral,' but that's not how it works. You don't make something viral," she said.

The problem for political memes, more generally, is that they are an expression of something more than an ad budget. Misha Leybovich said that a successful meme embodies the "organic energy that [they] represent." He cited the success of Andrew Yang's campaign (the #YangGang), and while he eventually dropped out of the 2020 race, "he lasted a lot longer than some professional politicians because his content game was so good." "What Bloomberg did," he added, "was to buy attention. However, it's not organic, and therefore there's no core truth to it."

Matt Charlton said if memes are a key battleground of 2020, it'll be for someone to demonstrate the clarity and authenticity necessary to take on Trump. "These people are making the mistake of fighting him where he's strong, and he's the king of flippant," making him the ideal king of meme culture. He said that when someone takes that stance, the only real solution is to "become the king of sincerity."