How to get and stay sober during the COVID-19 quarantine

Just because you're isolated doesn't mean you're alone.

The coronavirus pandemic and its resulting quarantine counter-measures have people around the world shuttered in their homes with little to do but fret. So it’s not surprising that a March survey from the American Psychiatric Association found that the disease has many people on edge. Out of 1,000 people surveyed, nearly half of respondents were anxious about contracting and dying from the virus, while 62 percent were worried about friends and family doing the same with more than 1 in 3 admitting that the pandemic was seriously impacting their mental health.

“What [people] are describing is a feeling of overwhelmed-ness,” Montgomery County Crisis Center manager Dorne Hill told the Washington Post recently.

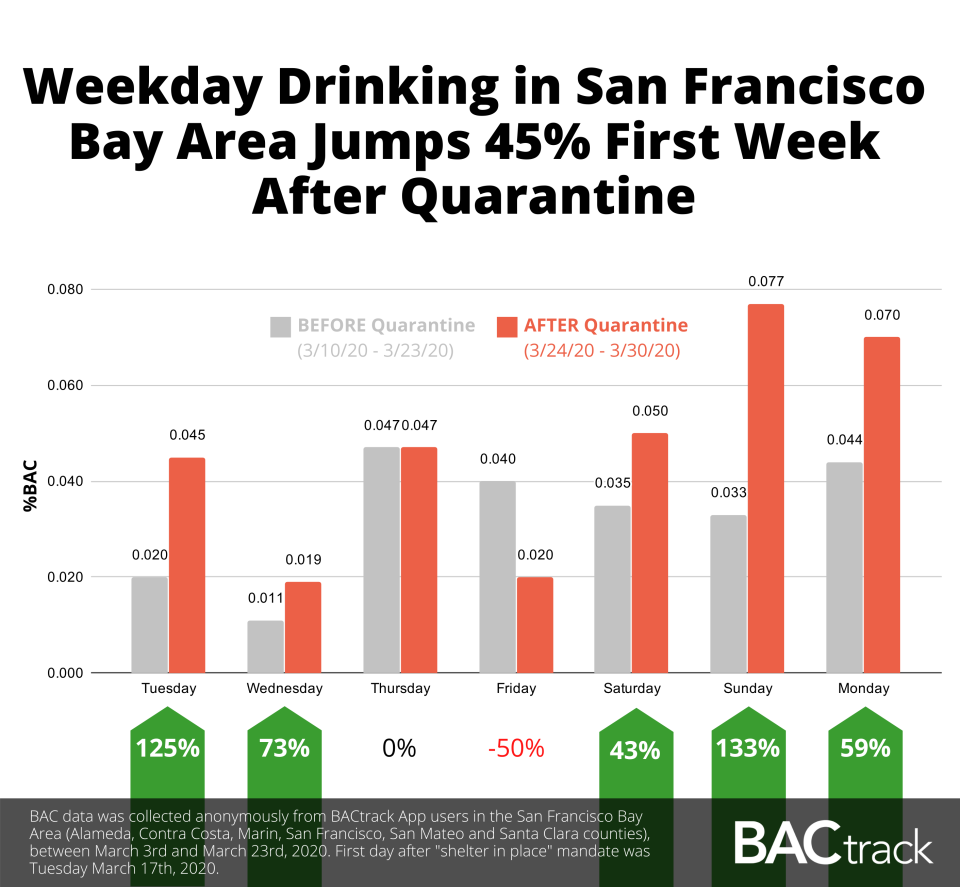

Nor should it come as any surprise that people, in these times of unprecedented worry, have turned to alcohol to help manage their stress. Vodka sales in Russia jumped 65 percent during the last week of March, after Vladimir Putin instituted a partial nationwide quarantine while BACTrack reports that weekday drinking throughout the San Francisco Bay Area spiked 45 percent during the first week of the California quarantine which began March 17th.

But for a lot of people, especially the estimated 14.4 million American adults who already struggle with Alcohol Use Disorder, the prospect of being cooped up inside with time to kill is no reason to celebrate. Compounding the problem is our need to physically distance from one another, which has all but eliminated in-person therapy, recovery and support groups. So how do you get and/or stay sober if you can’t leave your house? Thankfully a number of online resources have emerged in response to the crisis.

Remote therapy isn’t actually all that new. It’s one of a number of applications that make up the larger field of telehealth services. As the federal Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) defines it, telehealth is “the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration.” It’s effectively the same service, both in terms of quantity and quality, that’s available to patients in-person, just provided remotely.

The first proposed application came back in 1879 when the Lancet suggested leveraging new-fangled telephones to reduce the number of necessary doctor’s office visits. Today, telehealth is used in everything from radiology, dermatology, and dentistry to ophthalmology, optometry, and psychology. It’s been a boon to rural communities and other underserved populations, enabling them access to medical care without the need to drive for hours -- assuming they have access to a connected device. And in the age of COVID-19, telehealth is once again proving its worth.

In recent years, telehealth services have seen a spike in new interest from both policy makers and the public in general. Mei Kwong, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy in California, notes that around 2016, “Part of that reason was the technology itself was developing, much more rapidly. Technology itself was also becoming more integrated into our lives so I think people were starting to get that familiarity of, ‘Oh, we can use [connected devices] for so many different things -- like health care.’”

The CCHP has also seen a significant increase of inquiries about telehealth services over the last year. Kwong points out that in 2019, the CCHP received roughly 30 inquiries. In 2020, that number had ballooned to more than 300. With that growing interest has come a rapid expansion of available online support services such as doxy.me, TalkSpace, TheraNest, and BetterHelp, all of which offer video-based behavioral therapy as well as Woebot and Wyse, which offer text-based help. And with the White House’s recent decision to relax HIPAA requirements and allow people on Medicare to access telehealth programs, the number and scope of these services are certain to grow even further.

“We are doing a dramatic expansion of what’s known as telehealth for our 62 million Medicare beneficiaries, who are amongst the most vulnerable to the coronavirus,” Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said during a White House press conference in March. “Medicare beneficiaries across the nation—no matter where they live—will now be able to receive a wide-range of services via telehealth without ever having to leave home. These services can also be provided in a variety of settings, including nursing homes, hospital outpatient departments, and more.”

However, these mental health services, like virtually every other internet platform, are to a degree at risk of misuse and data breaches. Zoom-bombing has quickly spread from online classrooms to online therapists offices. What’s more, as John Torous, the director of the digital psychiatry division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, told Slate, “Hackers go for valuable data. Health data is very valuable, and insecure health systems are always primary targets for hackers.” This is why HIPAA requires online platforms not only be secure (at least more secure than what you’d typically find in Google Meet or FaceTime) but also employ business associate agreements certifying the emplacement of administrative safeguards against potential data leaks.

“Many video platforms today do already offer end-to-end encryption, so finding a secure platform is still good clinical practice,” Torous continued, adding that “You can have the best castle, the biggest moat, and biggest door, but if you leave the door open, it doesn’t matter.”

And it’s not just traditional medical experts that are utilizing teletherapy sessions during the quarantine, a number of informal support groups have sprung up in response as well. Laura McKowen, author of We Are The Luckiest: The Surprising Magic of a Sober Life, has started a free, Zoom-based sobriety support group which runs six days a week and reaches roughly 300 people per session.

A post shared by Laura McKowen (@laura_mckowen) on Apr 2, 2020 at 7:56am PDT

“There are all these people that now can't go to make it to real life support, they can't go to meetings or other programs they might be part of, and how impossible that would have been for me in my early sobriety.” McKowen told Engadget. “So I figured I had the platform to do it, I can do it so easily so why not?”

While not officially associated with Alcoholics Anonymous, these meetings are structured similarly. They begin with a brief meditation followed by a reading, “some kind of poem or book or passage that I love,” McKowen explained. “Then I have a speaker who speaks for 25 or so minutes, and then I open it up for people to share,” before closing with a second round of meditation.

And although these online sessions don’t offer the same physical connection as in-person meetings would -- those who share can’t hear the group’s applause once they finish, don’t enjoy the physical closeness and recognition from other attendees -- the added anonymity of being online has shown to have benefits as well. “If you were sitting in a room of 300 people, it’d feel wild,” McKowen said. “But because everyone's at home, it doesn't feel overwhelming.”

“A lot of people have identified themselves as someone who's never spoken in the meeting or never said anything to a group of people about their sobriety,” she continued. “So, that is really encouraging to me.”

To ensure that these meetings are safe spaces for those attending, McKowen maintains a tight rein on the operations. “I haven't experienced any zoom-bombing that's been happening because I haven't posted the meeting information on social media anywhere. ” Beyond that, all attendees are muted by default and can only be unmuted by McKowen while they’re sharing so nobody has to listen to the sound of 300 other people fidgeting while they share.

One participant in these meetings is Ginny Hogan, author of Toxic Femininity in the Workplace. Hogan, who has been sober for 13 months, has been isolating in Los Angeles since March. “The good is that I don't go to social events, which were a trigger for me,” she told Engadget. “I'm a stand up comedian and I used to be in bars a lot and that was always hard.”

On the other hand, Hogan notes that with the quarantine in place “it's a lot more isolating. I think like human connection is so important in overcoming addiction I can't imagine doing this if I were earlier in my sobriety.”

Her own experiences with online sobriety support groups to date have been less than stellar. “I went to AA a few times, but it wasn’t really for me, and a virtual AA meeting just because I was having trouble and it's just challenging,” Hogan explained. “I mean, it is already challenging to connect with everyone there because it's such a wide variety of people and then online with the extra distance of the Zoom call, it felt very difficult to form any sort of connection.”

Like any recovery program, online support groups are not a one-size-fits-all solution. Kwong advocates for those sorts of decisions to be made by medical professionals in conjunction with their patients. “You should just make it freely available to the healthcare provider to you when they think it is appropriate,” she said. “Leave it to their judgement.”

“That is what they have been trained for -- and another thing they're actually the one who's there in that situation with that patient -- because even if telehealth could be used medically to provide a service, you still want to take into account that it is appropriate for that person,” Kwong continued.

But even if the idea of online support groups makes your skin crawl, there are still plenty of resources at your disposal during this quarantine. One of the simplest means of cutting back your intake is to simply not keep alcohol in your home, McKowen notes. She also recommends that people “connect with some kind of community. There are so many Facebook groups, there are so many amazing people on Instagram... find a community of people that you can connect with and just dig in that way. Don't just white knuckle it and not drink.”

McKowen also suggests recurating your social media feeds to reduce the amount of alcohol related content that flows through your timeline. “A lot more people are talking about drinking right now,” she said. “If I was trying to get sober right now, I would really pay attention to what I was taking in as far as messaging from other people.”