The next generation of wearables will be a privacy minefield

What happens when we let companies track our emotions?

Facebook recently gave us our best glimpse yet into its augmented reality plans. The company will be piloting a new set of glasses that will lay the groundwork for an eventual consumer-ready product. The “research project,” called Project Aria, is still in very early stages, according to Facebook. There’s no display, but the glasses are equipped with an array of sensors and microphones that record video, audio and even its wearer’s eye movements — all with the goal of helping scientists at Facebook’s Reality Labs “figure out how AR can work in practice.”

Though the project is in its infancy, Facebook is clearly enthusiastic about its potential. “Imagine calling a friend and chatting with their lifelike avatar across the table,” the company writes. “Imagine a digital assistant smart enough to detect road hazards, offer up stats during a business meeting, or even help you hear better in a noisy environment. This is a world where the device itself disappears entirely into the ebb and flow of everyday life.”

But if you’re among those who believe Facebook already knows too much about our lives, you’re probably more than slightly disturbed by the idea of Facebook having a semi-permanent presence on your actual face.

Facebook, to its credit, is aware of this. The company published a lengthy blog post on all the ways it’s taking privacy into consideration. For example, it says workers who wear the glasses will be easily identifiable and will be trained in “appropriate use.” The company will also encrypt data and blur faces and license plates. It promises the data it collects “will not be used to inform the ads people see across Facebook’s apps,” and only approved researchers will be able to access it.

But none of that addresses how Facebook intends to use this data or what type of “research” it will be used for. Yes, it will further the social network’s understanding of augmented reality, but there’s a whole lot else that comes with that. As the digital rights organization Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) noted in a recent blog post, eye tracking alone has numerous implications beyond the core functions of an AR or VR headset. Our eyes can indicate how we’re thinking and feeling — not just what we’re looking at.

As the EFF’s Rory Mir and Katitza Rodriguez explained in the post:

How we move and interact with the world offers insight, by proxy, into how we think and feel at the moment. If aggregated, those in control of this biometric data may be able to identify patterns that let them more precisely predict (or cause) certain behavior and even emotions in the virtual world. It may allow companies to exploit users' emotional vulnerabilities through strategies that are difficult for the user to perceive and resist. What makes the collection of this sort of biometric data particularly frightening, is that unlike a credit card or password, it is information about us we cannot change. Once collected, there is little users can do to mitigate the harm done by leaks or data being monetized with additional parties.

There’s also a more practical concern, according to Rodriguez and Mir. That’s “bystander privacy,” or the right to privacy in public. “I'm concerned that if the protections are not the right ones, with this technology, we can be building a surveillance society where users lose their privacy in public spaces,” Rodriguez, International Rights Director for EFF, told Engadget. “I think these companies are going to push for new changes in society of how we behave in public spaces. And they have to be much more transparent on that front.”

In a statement, a Facebook spokesperson said that “Project Aria is a research tool that will help us develop the safeguards, policies and even social norms necessary to govern the use of AR glasses and other future wearable devices.”

Facebook is far from the only company to grapple with these questions. Apple, also reportedly working on an AR headset, also seems to be experimenting with eye tracking. Amazon, on the other hand, has taken a different approach when it comes to the ability to understand our emotional state.

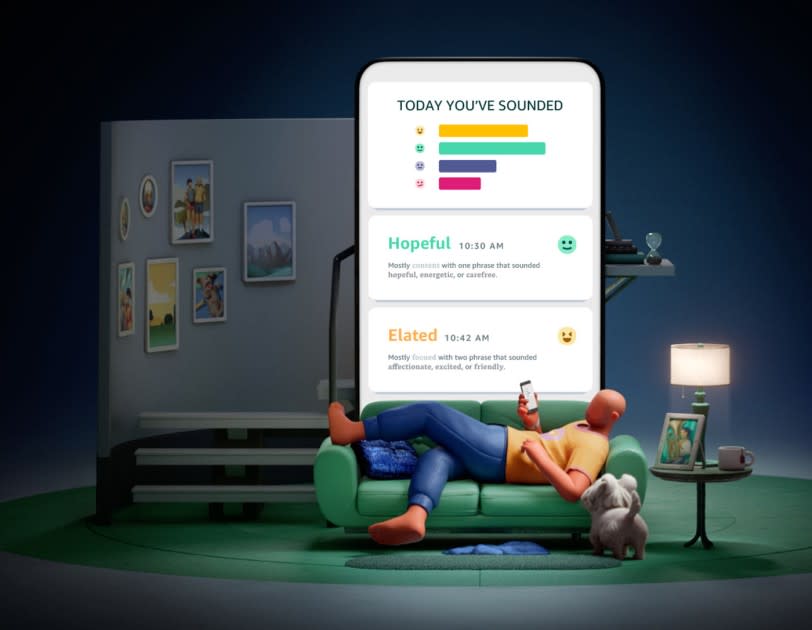

Consider its newest wearable: Halo. At first glance, the device, which is an actual product people will soon be able to use, seems much closer to the kinds of wrist-worn devices that are already widely available. It can check your heart rate and track your sleep. It also has one other feature you won’t find on your standard Fitbit or smartwatch: tone analysis.

Opt in and the wearable will passively listen to your voice throughout the day in order to “analyze the positivity and energy of your voice.” It’s supposed to aid in your overall well being, according to Amazon. The company suggests that the feature will “help customers understand how they sound to others,” and “support emotional and social well-being and help strengthen communication and relationships.”

If that sounds vaguely dystopian, you’re not alone, the feature has already sparked more than one Black Mirror comparison. Also concerning: history has repeatedly taught us that these kinds of systems often end up being extremely biased, regardless of the creator’s intent. As Protocol points out, AI systems tend to be pretty bad at treating women and people of color the same way they treat white men. Amazon itself has struggled with this. A study last year from MIT’s Media lab found that Amazon’s facial recognition tech had a hard time accurately identifying the faces of dark-skinned women. And a 2019 Stanford study found racial disparities in Amazon’s speech recognition tech.

So while Amazon has said it uses diverse data to train its algorithms, it’s far from guaranteed that it will treat all its users the same in practice. But even if it did treat everyone fairly, giving Amazon a direct line into your emotional state could also have serious privacy implications.

And not just because it’s creepy for the world’s biggest retailer to know how you’re feeling at any given moment. There’s also the distinct possibility that Amazon could, one day, use these newfound insights to get you to buy more stuff. Just because there’s currently no link between Halo and Amazon’s retail service or Alexa, doesn’t mean that will always be the case. In fact, we know from patent filings Amazon has given the idea more than a passing thought.

The company was granted a patent two years ago that lays out in detail how Alexa may proactively recommend products based on how your voice sounds. The patent describes a system that would allow Amazon to detect “an abnormal physical or emotional condition” based on the sound of a voice. It could then suggest content, surface ads and recommend products based on the “abnormality.” Patent filings are not necessarily indicative of actual plans, but they do offer a window into how a company is thinking about a particular type of technology. And in Amazon’s case, its ideas for emotion detection are more than a little alarming.

An Amazon spokesperson told Engadget that “we do not use Amazon Halo health data for marketing, product recommendations, or advertising,” but declined to comment on future plans. The patent offers some potential clues, though.

“A current physical and/or emotional condition of the user may facilitate the ability to provide highly targeted audio content, such as audio advertisements or promotions,” the patent states. “For example, certain content, such as content related to cough drops or flu medicine, may be targeted towards users who have sore throats.”

In another example — helpfully illustrated by Amazon — an Echo-like device recommends a chicken soup recipe when it hears a cough and a sniffle.

As unsettling as that sounds, Amazon makes clear that it’s not only taking the sound of your voice into account. The patent notes that it may also use your browsing and purchase history, “number of clicks,” and other metadata to target content. In other words: Amazon would use not just your perceived emotional state, but everything else it knows about you to target products and ads.

Which brings us back to Facebook. Whatever product Aria eventually becomes, it’s impossible now, in 2020, to fathom a version of this that won’t violate our privacy in new and inventive ways in order to feed into Facebook’s already disturbingly-precise ad machine.

Facebook’s mobile apps already vacuum up an astounding amount of data about where we go, what we buy and just about everything else we do on the internet. The company may have desensitized us enough at this point to take that for granted, but it’s worth considering how much more we’re willing to give away. What happens when Facebook knows not just where we go and who we see, but everything we look at?

A Facebook spokesperson said the company would “be up front about any plans related to ads.”

“Project Aria is a research effort and its purpose is to help us understand the hardware and software needed to build AR glasses – not to personalize ads. In the event any of this technology is integrated into a commercially available device in the future, we will be up front about any plans related to ads.”

A promise of transparency, however, is much different than an assurance of what will happen to our data. And it highlights why privacy legislation is so important — because without it, we have little alternative than to take a company’s word for it.

“Facebook is positioning itself to be the Android of AR VR,” Mir said. “I think because they're in their infancy, it makes sense that they're taking precautions to keep data separate from advertising and all these things. But the concern is, once they do control the medium or have an Android-level control of the market, at that point, how are we making sure that they're sticking to good privacy practices?”

And the question of good privacy practices only becomes more urgent when you consider how much more data companies like Facebook and Amazon are poised to have access to. Products like Halo and research projects like Aria may be experimental for now, but that may not always be the case. And, in the absence of stronger regulations, there will be little preventing them from using these new insights about us to further their dominance.

“There are no federal privacy laws in the United States,” Rodriguez said. ”People rely on privacy policies, but privacy policies change over time.”