Chris Ferguson

Latest

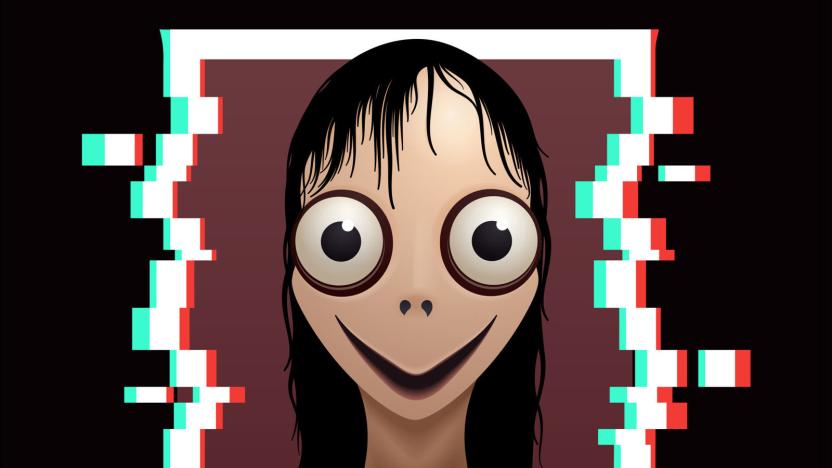

Adults are the only ones who fell for the Momo hoax

Oh man, we really do live on the dumbest timeline. You probably recognize the horrifying visage you see above: it's Momo, the mascot for the internet's newest outrage sensation. The Momo Challenge, as it's called, reportedly encourages children and teens to commit increasingly brazen acts of self-harm and criminality. It's also a complete and utter, laughably obvious hoax. Your kids are fine, literally nobody on the entire internet has fallen for this -- except, well, countless adults, law enforcement agencies, news outlets and school districts. You know, the responsible folks. The Momo in the picture, it should be noted, is real. The figure is not digitally generated, nor is it photoshopped. "Momo" actually exists as a static sculpture, dubbed "Mother Bird," and was created by Japanese artist Keisuke Aisawa, who made it for his employer: the special effects company, Link Factory. It was first displayed in a Tokyo horror-art gallery back in 2016. View this post on Instagram 台風だから幽霊の絵見てきた 幽霊はいいぞ #幽霊画廊 #猫将軍 A post shared by さとう【生ビール嫌い】 (@j_s_rock) on Aug 22, 2016 at 7:13am PDT During its run at the gallery, visitors snapped pictures of the sculpture, officially titled "Mother Bird," and posted them to Instagram. Eventually the images made their way to Reddit's r/creepy forum where it was further disseminated across the internet, all the while morphing into the Momo Challenge. Momo made her first appearance in the mainstream early last year after authorities in Argentina warned of a "WhatsApp terror game" following the suicide of a 12-year-old girl. In the following months, the rumor of "El Momo" made waves in Mexico before eventually landing on news desks here in the US that fall. By that point, school officials and local police departments were claiming that Momo was being spliced into children's programming on YouTube and spread among WhatsApp users. The panic even spread to the UK at the start of 2019 before hopping the pond back to the United States late last month. At the end of February, a Twitter user going by Wanda Maximoff issued the following warning in a now-deleted tweet, The Atlantic reports, "Warning! Please read, this is real. There is a thing called 'Momo' that's instructing kids to kill themselves. INFORM EVERYONE YOU CAN." That tweet was viewed more than 22,000 times over the next few days before exploding onto the mainstream consciousness thanks to Kim Kardashian discussing the Challenge with her 129 million-odd Instagram followers. Yet despite there being no confirmed cases of kids and teens even participating in this activity -- much less dying from it -- adults and authority figures around the country have flipped out, rushing to protect children from an online menace that doesn't actually exist. What we have here is a full-blown moral panic. I wish I could tell you that moral panics were something new but, as Chris Ferguson, professor and co-chair of psychology at Florida's Stetson University, explains to Engadget, they've been around for millenia. "I mean, you can see narratives in Plato's dialogues where Athenians are talking about Greek plays -- that they're going to be morally corrupting, that they're going to cause delinquency in kids," Ferguson points out. "That's why Socrates was killed, right? Essentially, that his his ideas were going to corrupt the youth of Athens. Socrates was the Momo challenge of his day." Unfortunately, humanity appears to still be roughly as gullible as we were in the 5th century BC as new moral panics crop up with uncanny regularity. In recent decades we've seen panics about Dungeons and Dragons leading to Satanism, hidden messages in Beatles songs, killer forest clowns, the Blue Whale, the Knockout Game, and the Tide Pod Challenge. Despite the unique nature of threat presented in each panic, this phenomenon follows a pair of basic motifs, Ferguson explained. "There's this inherent protectiveness of kids," he said. "There's also the sense of like, kids are idiots and therefore adults have to step in and 'do something' -- hence the idea that your teenager can simply watch a YouTube video and then suddenly want to kill themselves. It's ridiculous if you think about if for 30 seconds but, nonetheless, this is an appealing sort of narrative." "There's the general sense of teens behaving badly and technology oftentimes being the culprit in some way or another," Ferguson continued. "It just seems that we're kind of wired, particularly as we get older, to be more and more suspicious of technology and popular culture." That is due, in part, because the popular culture right now isn't the popular culture that the people in power grew up with. It's a "kids today with their music and their hair" situation, Ferguson argues. He points out that "Mid-adult mammals tend to be the most dominant in social species," but as they age, their power erodes until they are forced out of their position by a younger, fitter rival. "As we get older, eventually we're going to become less and less relevant," he said. Faced with that prospect, older members of society may begin to view fresh ideas and new technologies as evidence of society's overall moral decline. kids: we're afraid of dying because of climate change boomers: that's ridiculous! we're afraid a Japanese half-woman half-bird sculpture is trying to kill you through the internet — Notorious Sexual Freak Mrs. Beverly Bighead (@mechapoetic) March 2, 2019 When presented with unfamiliar tech and notions, "we may have the sense that we're losing control of culture gradually," Ferguson speculates. "That makes [moral panicking] easy for us because of that anxiety to push back against anything new." Conversely, the motivations for people to commit these hoaxes is depressingly straightforward: it's fun being a jerk online. Trolling folks into believing that a nightmarish chicken lady is grooming your kids for suicide by targeting their Peppa Pig videos is done for a variety of reasons: simple amusement, as attention seeking behavior, or as an act of revenge. "I think sometimes people like to start these things because they want the reaction," Ferguson said. "They want to feel like they're smarter than all these knuckleheads," who fell for their ruse. Unfortunately, in today's social media landscape where attention serves as the de facto currency, simply ignoring the trolls -- hoping that they'll get bored and quit -- isn't likely to happen. And for as long as people keep reproducing, society will be faced with intergenerational strife as "the kids with their music and their hair" grow up, rightfully displace their elders and assert themselves as gatekeepers of the dominant culture. Even when faced with their own mortality and declining social influence, today's panic stricken adults do still have a quantum of solace: Aisawa announced earlier this week that, in the wake of the Momo Challenge fallout, he has destroyed the original sculpture. "It doesn't exist anymore, it was never meant to last," Aisawa told The Sun. "It was rotten and I threw it away. The children can be reassured Momo is dead – she doesn't exist and the curse is gone."

MMO Family: Are video games stressing kids out?

Video games get blamed for all sorts of societal problems, particularly for young children. Violence, obesity, and laziness are just the tip of the iceberg. And a recent article from Amanda Enayati adds one more potential problem: stress. Growing up is complicated enough, but are video games making it even harder to be a happy, relaxed kid? Enayati, CNN Health's stress columnist and the technology and stress correspondent for PBS MediaShift, says it's complicated but points to a few studies that argue the pros and cons. Let's take a look at the debate over whether video games might be too stressful for children.

Study finds 'conclusive evidence' of games/violence link?

Iowa State University's Craig Anderson has led a study which claims 'conclusive evidence' of a link between violent video games and increased aggression in children. The findings (and indeed the validity of the study) have been challenged by Christopher Ferguson whose research at Texas A&M International University has found the opposite. Ferguson finds a number of flaws in the Iowa State study, which he says demonstrates only "weak correlations". We can spot a few of our own. For example there is no definitive usefully testable method for determining aggressive tendencies. By failing to factor in extraneous variables, the study results could quite easily be interpreted to indicate that aggressive tendencies cause kids to spend more time playing violent video games. Just because two things are correlated does not mean that one causes the other. The majority of dead people have eaten meat. That doesn't mean that meat kills people.