The delightful (and dangerous) world of DIY kits

We can't always work alongside a pro to see what makes things tick, and that's where do-it-yourself projects come in handy. They're the entertaining alternative to learning a new skill. In this week's Rewind, we've tracked down a series of kits that were released over the years, which have sought to inform us in fields like electronics, music and the secrets of the scientific world. Read on to see some of the incredible (and occasionally dangerous) DIY projects that have been shared with curious minds.

Building the future

New Haven, Connecticut-based Mysto Manufacturing Company began selling Erector Sets in 1913, but three years later it became the A.C. Gilbert Company. Erector Sets were boxes of metallic, project-focused parts that helped enterprising minds get a grip on engineering and architecture. Kids could choose from projects ranging from remote-controlled robots to carousels, trains and trucks -- all of which included electric motors and controls for actual functionality.

Fun with radiation

Uranium and children are an unlikely pairing. But during the US "Uranium Rush" in the '40s and '50s, young and old alike were urged to join the hunt for the elusive metal by building their very own radiation-detecting Geiger counters. These kits were relatively easy to make, often requiring just an evening of work, and even the Atomic Energy Commission joined in the fun by providing detailed specs on how to build one. Most uranium ore in its unrefined state is less dangerous than you would think, but sending junior out to search for it isn't considered a particularly safe hobby -- at least not anymore.

Chemical reactions

A little practical knowledge goes a long way and after the success of its Erector Set, the A.C. Gilbert Company got all starry eyed about teaching children the hidden wonders of the scientific world. Sure, buyers are warned that the kit isn't for children who couldn't read and understand the accompanying guide, but safety standards were still a bit lax. Asbestos was included in some of the kits, and many of the experiments involved fun with combustion.

Atomic energy and you

If a home chemistry set sounded like a great way for your little ones to learn about nature's complexity, perhaps the 1951 U-238 Atomic Energy Lab (also by A.C. Gilbert) would have knocked it out of the park. This kit had a comic-strip-inspired guidebook called "Learn How Dagwood Splits the Atom" and included a Geiger counter. The fun would've started once you switched on the radiation-detecting tool, since the kit conveniently included four types of uranium ore.

The computer age

After years of selling light aircraft and related accessories, the Heath Company acquired a large amount of electronics parts to help hobbyists build their own machines for just a fraction of the cost of ready-made versions. In the mid-'50s, the company began releasing a series of analog computer kits like the H1 (shown). Priced from $475 to $945 (depending on size), this was an incredibly affordable computer for its time. They weren't necessarily for beginners; the H1 could help speed up complex equations and was more than "suitable for use as a design tool in industry and universities."

Sound science

One of the earliest electronic instruments (a voltage-controlled synthesizer) was made from scratch by Hugh Le Caine in the mid-'40s. Not all music fans would have to go to those lengths though. Hobbyist magazines like Practical Electronics offered all-in-one kits for producing your own futuristic sound machines like the 1974 PE Minisonic. This battery-powered kit included its own speakers, could last about 50 hours on a charge and let users tweak sounds through a series of modulators, envelopes and filters.

BASIC building blocks

The microcomputer revolution got its start around 1974 thanks to affordable kits like the Altair 8800. The input/output was limited to lights and toggle switches, but it still turned into a hot item, selling around 5,000 units in its first year. It was sold by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry System (MITS) and ran on Intel's 8080 microprocessor. Bill Gates and Paul Allen bought one of the Altair 8800s and used it to create the Altair BASIC interpreter (the first Micro-Soft product), which was also distributed by MITS for a short time.

Time and technology

Clive Sinclair made a name for himself by selling a variety of electronics products that could be purchased pre-assembled or as a do-it-yourself kit. In 1975, his company released the Sinclair Black Watch, a futuristic wearable that had a five-digit LED display and two panels as the only buttons.

Robot starter kit

Lego drew some inspiration from MIT for the heart of its Mindstorms toys in 1998. The programmable core of the system was the RCX "brick" (based on Logo Computer Systems software) and came with a series of interchangeable parts and sensors that helped teach kids some of the basics in robotics.

Electronics engineering

LittleBits launched its first electronics kits in 2011. Magnetically connectable parts like fans, pressure sensors and motors help young minds easily create fully functioning toys, tools and devices through circuit connections. Adafruit, which has been supporting electronics hobbyists since 2005, provides a growing array of components and projects for slightly more advanced electronics hobbyists.

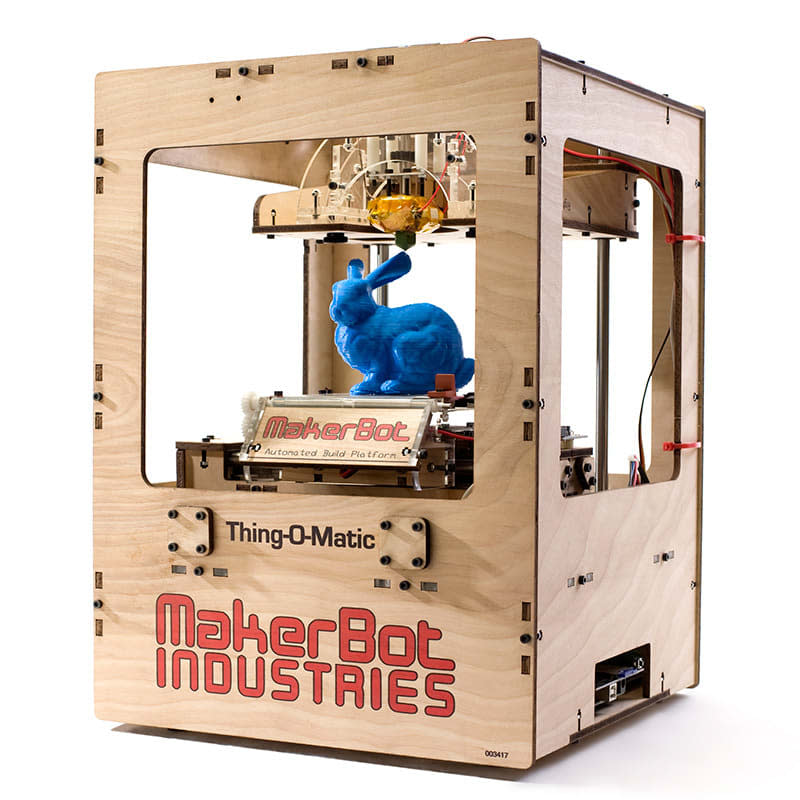

Creating creativity

Most do-it-yourself projects provide the instructions and components to build a specific device, but 3D printers open up a new world of possibilities. Building on the success of the RepRap Project, MakerBot offered its first 3D printer in 2010: the Thing-O-Matic. The device required some assembly (of course), but once it was up and running, you could design and print almost anything, even parts for your own do-it-yourself kits.

![<p>New Haven, Connecticut-based Mysto Manufacturing Company began selling Erector Sets in 1913, but three years later it became the A.C. Gilbert Company. Erector Sets were boxes of metallic, project-focused parts that helped enterprising minds get a grip on engineering and architecture. Kids could choose from projects ranging from remote-controlled robots to carousels, trains and trucks -- all of which included electric motors and controls for actual functionality.</p>

<p></p>

<p>[Image: meccanohig/Flickr]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/ytMvOweHtIJUrNHFI8NZIw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTc4NQ--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/bn_1naMPWTZr1.n2o4r0Yw--~B/aD02NTQ7dz04MDA7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/314/276/6/S3142766/slug/l/erector-set-1949-twelve-and-a-half-800-1.jpg)

![<p>Uranium and children are an unlikely pairing. But during the US "Uranium Rush" in the '40s and '50s, young and old alike were urged to join the hunt for the elusive metal by building their very own radiation-detecting Geiger counters. These kits were relatively easy to make, often requiring just an evening of work, and even the Atomic Energy Commission joined in the fun by providing detailed specs on how to build one. Most uranium ore in its unrefined state is less dangerous than you would think, but sending junior out to search for it isn't considered a particularly safe hobby -- at least not anymore.</p>

<p>[Image: <a href="http://www.popsci.com/archive-viewer?id=KS0DAAAAMBAJ&pg=null&query=march%201950">Popular Science Archive</a>]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/_U567dwPbvW4QtDh7Hhlqw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTEzMzY-/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/qvmu693WHTk6BdqsIdoDpA--~B/aD04MDA7dz01NzU7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/313/480/7/S3134807/slug/l/geiger-aec-spec-popsci-800-1.jpg)

![<p>A little practical knowledge goes a long way and after the success of its Erector Set, the A.C. Gilbert Company got all starry eyed about teaching children the hidden wonders of the scientific world. Sure, buyers are warned that the kit isn't for children who couldn't read <em>and</em> understand the accompanying guide, but safety standards were still a bit lax. Asbestos was included in some of the kits, and <a href="http://keeline.com/chem/1936-Gilbert_Chemistry_Outfit_Manual_M1706.pdf">many of the experiments</a> involved fun with combustion.</p>

<p>[Image: Courtesy of the <a href="https://www.chemheritage.org/">Chemical Heritage Foundation</a>]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/lQs.9B4o9LLNadXMoSnxrA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTgwOQ--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/cj71ilgF7wYjWsxAAe1ecg--~B/aD02NzQ7dz04MDA7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/314/041/9/S3140419/slug/l/gilbert-chemical-800-1.jpg)

![<p>If a home chemistry set sounded like a great way for your little ones to learn about nature's complexity, perhaps the 1951 U-238 Atomic Energy Lab (also by A.C. Gilbert) would have knocked it out of the park. This kit had a comic-strip-inspired guidebook called "Learn How Dagwood Splits the Atom" and included a Geiger counter. The fun would've started once you switched on the radiation-detecting tool, since the kit conveniently included four types of uranium ore.</p>

<p>[Image: <a href="http://www.acghs.org/">A.C. Gilbert Heritage Society</a>]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/F_JS2JGEd0FFyiR25DdJFw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTk2MA--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/S45zxR30rnIdrlGxCKcWLQ--~B/aD04MDA7dz04MDA7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/314/221/5/S3142215/slug/l/gilber-atomic-lab-800-1.jpg)

![<p>After years of selling light aircraft and related accessories, the Heath Company acquired a large amount of electronics parts to help hobbyists build their own machines for just a fraction of the cost of ready-made versions. In the mid-'50s, the company began releasing a series of analog computer kits like the H1 (shown). Priced from <a href="http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/text/Heath/Heath.Analog.1956.102646297.pdf">$475 to $945</a> (depending on size), this was an incredibly affordable computer for its time. They weren't necessarily for beginners; the H1 could help speed up complex equations and was more than "suitable for use as a design tool in industry and universities."</p>

<p>[Image: stiefkind/Flickr *incorrectly listed as the EAC-1]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/I7fgz6l0G1cT5pyqzqXElw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY1NA--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/LZcNfuTWhQmdB1XP1tRkNQ--~B/aD01NDU7dz04MDA7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/313/636/7/S3136367/slug/l/heathkit-eac1-800-1.jpg)

![<p>One of the earliest electronic instruments (a voltage-controlled synthesizer) was made from scratch by <a href="http://www.hughlecaine.com/en/sackbut.html">Hugh Le Caine</a> in the mid-'40s. Not all music fans would have to go to those lengths though. Hobbyist magazines like <em>Practical Electronics</em> offered all-in-one kits for producing your own futuristic sound machines like the 1974 PE Minisonic. This battery-powered kit included its own speakers, could last about 50 hours on a charge and let users tweak sounds through a series of modulators, envelopes and filters.</p>

<p>[Image: <a href="http://www.epemag3.com/index.html">Everyday Practical Electronics</a> via <a href="http://www.timstinchcombe.co.uk/index.php?pge=pemini">Tim Stinchcombe</a>]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/HgSrpQJrLF7mS2kvUz39QQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTEzMDI-/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/vN3TfMCB.N3tJTre2YtF5g--~B/aD04MDA7dz01OTA7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/313/651/0/S3136510/slug/l/minisonic-800-1.jpg)

![<p>The microcomputer revolution got its start around 1974 thanks to affordable kits like the Altair 8800. The input/output was limited to lights and toggle switches, but it still turned into a hot item, selling around 5,000 units in its first year. It was sold by <a href="http://www.engadget.com/2010/04/02/dr-henry-edward-roberts-personal-computing-pioneer-loses-batt/">Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry System (MITS)</a> and ran on Intel's 8080 microprocessor. Bill Gates and Paul Allen bought one of the Altair 8800s and used it to create the Altair BASIC interpreter (the first Micro-Soft product), which was also distributed by MITS for a short time.</p>

<p>[Image: AP Photo/Heinz Nixdorf Museumsforum]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/sn5a4dQ_mf2opoVytaYFwQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcxMA--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/zJwBunK7mv2Gap38OhkvTw--~B/aD01OTI7dz04MDA7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/313/474/9/S3134749/slug/l/altair-8800-800-1.jpg)

![<p>Clive Sinclair made a name for himself by selling a variety of electronics products that could be purchased pre-assembled or as a do-it-yourself kit. In 1975, his company released the Sinclair Black Watch, a futuristic wearable that had a five-digit LED display and two panels as the only buttons.</p>

<p>[Image: SSPL/Getty Images]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/N1.yuS5VqCqQEA2hg0BS7w--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTg2NQ--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/jMzb5_C.SQ9fKTCnA1Jt1Q--~B/aD03MjE7dz04MDA7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/313/474/6/S3134746/slug/l/sinclair-black-watch-800-1.jpg)

![<p>Lego drew some inspiration from MIT for the heart of its Mindstorms toys in 1998. The programmable core of the system was the RCX "brick" (based on Logo Computer Systems software) and came with a series of interchangeable parts and sensors that helped teach kids some of the basics in robotics.</p>

<p>[Image: wiredforlego/Flickr]</p>

<p></p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/PrX.Vd7Scu32c7FmH9Q4QA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTExMjA-/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/OIhoo5GMvq97eL60Vje7Qw--~B/aD04MDA7dz02ODY7YXBwaWQ9eXRhY2h5b24-/https://www.blogcdn.com/slideshows/images/slides/313/651/7/S3136517/slug/l/lego-mindstorms-ev3-800-1.jpg)