The struggle to adapt storytelling for virtual reality

"We're ready to tell stories, but how do you do that in VR?" asks Oscar-winning art director Robert Stromberg.

Storytelling in virtual reality has yet to take shape. While the simulated world of gaming has proved the visual capabilities of the medium, few have taken a crack at the art of building a compelling narrative.

But now that the battle of the VR headsets is fully under way, a shift is evident. Content studios seem to be getting ready for the next wave of virtual reality. Over the past week alone, major VR studios have announced investments from Hollywood studios that seem indicative of the cinematic experiences to come. Within, formerly known as VRSE, has raised $12.56 million from investors including Andreessen Horowitz and 21st Century Fox, Felix & Paul Studios has seen $6.8 million in a round led by Comcast, and Virtual Reality Company (VRC) got $23 million from Beijing's Hengxin Mobile Business in exchange for exclusive distribution rights in China.

There's been a lot of hype and cash flow around VR in the past couple of years. But there's little insight into what it takes to build a great experience outside gaming. Can filmmakers turn into VR makers? Will they infuse this immersive format with dramatic storytelling? Or will it remain a simulated world that's best suited for interactive gaming?

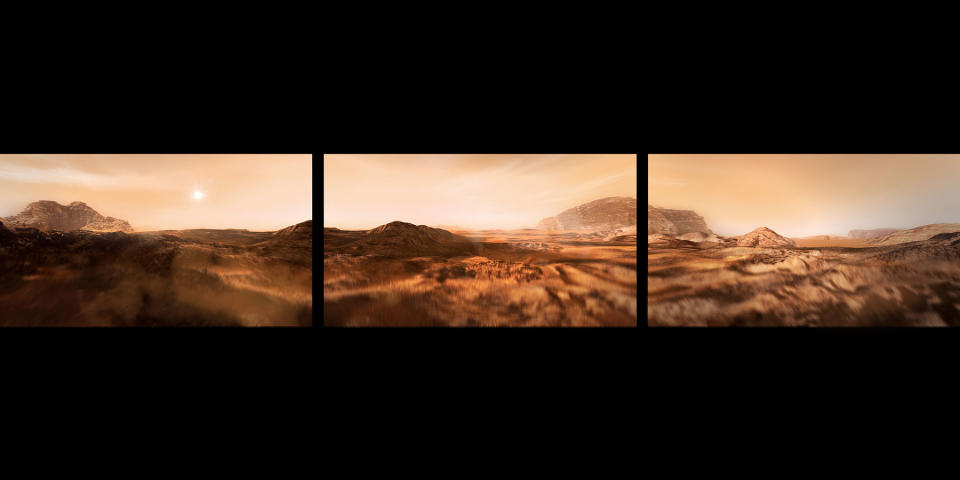

The experience that came closest to immersive cinema was VRC's The Martian VR Experience at the beginning of the year. It followed director Ridley Scott's visual cues, but unlike other Hollywood companion pieces that came before, this one took on a life of its own. It gave VR headset wearers the ability to inhabit the film as Mark Watney (the abandoned astronaut played by Matt Damon). The isolation of being stranded and the triumph of being rescued in space made for a powerful experience.

A still from "The Martian VR Experience" (Image credit: Virtual Reality Company)

The Martian VR epitomized the dramatic capabilities of the visual medium. Oscar-winning production designer and VRC founder Robert Stromberg infused the experience with a narrative and emotions in a way that hadn't been successful before. His ability to build the cinematic experience stemmed from his award-winning career in Hollywood.

For well over a decade, Stromberg has been a VFX specialist who has worked with some of the biggest names in Hollywood, including Steven Soderbergh, Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg. His list of accolades for production design and visual effects includes five Emmys (including Star Trek: The Next Generation and Boardwalk Empire) and two Academy Awards (for James Cameron's Avatar and Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland). Last year he also won three Cannes Lions for What Lives Inside, an Intel- and Dell- sponsored series that premiered on Hulu.

In light of the new funding for VRC and the buzz around Steven Spielberg's VR debut with the company that he backs as an adviser, I spoke with Stromberg about what it takes to build compelling narratives in an immersive format.

You made a push for visual effects in the '90s, and now with VRC you're tackling another visual medium. What drew you to virtual reality, and what led to the company?

I've been a creative person since I was a small child, and I always dreamed of the idea of transporting myself to a world that didn't exist. Virtual reality allowed me to step into worlds that could be created, and that to me was not only magic but a shock: I didn't think it would be possible in my lifetime. I spent my entire career building worlds for film. When I was doing Avatar, that's when I started to see the technology changing and we were able to create a 360-degree world. We were making that film with a virtual camera, and I knew that it was only a matter of time before people would be able to put that in a viewing system that would immerse that person in the world.

I kept my eye on that and went off and directed Maleficent. Around the same time [in 2014] I heard that Oculus was being bought by Facebook. I actually cold-called Oculus, which at the time was just a startup at Irvine. I introduced myself, and they invited me down to see what they were up to. It became very apparent to me what the future was going to be. I decided that day to form VRC.

What I recognized at the time was that the technology was going to be there but no one was talking about content. It was the perfect opportunity to step into the world of content, and I knew it needed to be symbiotic with the tech for it to work.

Rick Carter, Robert Stromberg and Kim Sinclair with their art direction Oscars for "Avatar" in 2010 (Image credit: Matt Sayles/AP)

You've said before, "The mediums will change, but the storytelling will stay the same." Does it really stay the same with VR, or does the medium require an approach that's different from the standard format of films?

It's something brand new, like television was to theater. VR is a cross-pollination between what you might consider a live performance and cinematic storytelling. To me it's something that is in its fledgling stages, and I still don't believe that the nut has been cracked yet. We're ready to tell stories, but how do you do that in VR? A lot of people are pushing that dynamic to find the combination that works for them, including myself. I believe that within months to a year that sort of dramatic storytelling event will happen. A lot of people are doing one-off events, but at VRC what we're trying to do is create that first sort of fully developed, cinematic, emotional storytelling content. I believe it's very close; it's just a matter of the tech being at a point where we can utilize it in a way that we create true emotions when someone is viewing a story.

What makes a good cinematic VR experience? What are the things to focus on, and what are the pitfalls of the medium?

Two years ago, I had to prove to myself that this was a medium you could approach with a cinematic eye. So the first thing I did was create a four-minute dream world with cinematic music and all the bells and whistles. That's when it struck me that it could be big and dramatic in this new medium. The Martian was on the heels of that. It started as a storytelling vehicle, a condensed version of the film, but then we introduced an interactive component. It's kind of a hybrid -– a cross between an observer and a participant.

I think that's going to be the definition of how you tell a story: Are you an observer, or are you a participant? If you look at it as a stage play, you go to a theater and watch a performance live and you have a choice of where to look onstage. If you were to put yourself on the stage, it would be a different experience. You would feel like you were intruding if you were just an observer, and if you got right up in people's conversations you would feel awkward because you would feel like you're a part of it. We're doing a lot of psychological tricks with storytelling where you're a watching a performance as opposed to being part of it or you're in an interactive setting and you want to see a character in the story.

A still from "There," a VR experience directed by Robert Stromberg

The visual medium has extended the capabilities of experiencing things. But in what ways does it limit storytelling, and how do you work around it?

Let's take The Revenant as an example. You're using the camera as a framing device and using the movement of the camera to get emotion. You have these long, extended shots that move from beat to beat that still tell a story. But traditional editing can be jarring if you're immersed in a world, so that's one of the things we're experimenting with: how to transition smoothly but still feel like you're moving the story along.

There are ways to transition in VR, too, clever ways to sort of move from one experience to the next. With The Martian, I came up with what I call the "box cutter." You have 3D images on 3D screens that follow the edit of the film itself, and it pushes the story along. It's sort of a cheat in a way, but it is a technique. I think we're going to find many methods to transition over time. In the last year, the technology has reached a point where we can do things we couldn't do even two years ago. Live capture, for instance. We're capturing actual performances from actors and putting them in this world. When we have all the elements in our toolbox then we can dig and find the emotion in the stories. Until now it's been parlor tricks to say, "Look at what VR can do!"

(Left to right) VRC co-founders Joel Newton and Robert Stromberg with recording artist Anderson Paak and co-founder Guy Primus. (Image credit: Vivien Killilea/Getty Images)

How far are we from seeing long-form narratives? What are the limitations with time when you want to immerse someone into a virtual world?

The Martian started out as a 12-minute experience, which ended up being 20 to 28 minutes, depending on what you did with the interactive component. What we realized is that people didn't have a problem in an environment that long. There's the obvious motion sickness that we're up against, but overall what we're trying to do is find what we can do with the camera. How fast can we move it? What are the dos and don'ts of being immersed? What makes people uncomfortable?

One of the biggest things I learned from The Martian was that the brain was so tuned in that you had to make sure the horizon was accurate. Otherwise your mind tells you something's wrong. There was one portion where people had an uncomfortable feeling, but when we cracked the horizon issue it went away. So everything is still being wind tunnel tested. Over time we'll learn what does and doesn't make somebody comfortable. I think maybe there'll be a rating system for VR where you'll know going in what level you're comfortable with. It'll take shape, but we're just not in that place yet.

What are you currently working on?

We're involved with many things, but what we're focused on is high-end content. Something that's going to be worth monetizing eventually. That's a whole other discussion about how it will be presented to the masses -– whether it's mobile, Oculus, [HTC] Vive, Playstation [VR]. We're working with all of those systems to make sure we cover the most territory.

"Over time we'll learn what does and doesn't make somebody comfortable. I think maybe there'll be a rating system for VR where you'll know going in what level you're comfortable with."

We're working on a project with Steven [Spielberg]. I can't say what it is yet, but I can say that it's a series. Going back to the time limitation, I think the first version in terms of storytelling content will be episodic and shorter. We have to be mindful of -- who's going to be the first adopters? It's younger people and gamers. When we bring kids in to see the threshold, we find that kids can stay in there all day. The first round we'll be looking at 10- to 12-minute episodes. Eventually when we get into longer formats, I see a version where we introduce the idea of intermissions or breaks, so you have the option to continue or take a break. It worked with films in the old days, when they were three or four hours long. It wasn't only to get popcorn but to settle. I can see that related to the future content that comes out of VR as well.

What would you say is the general perception of VR in Hollywood? Is it considered a buzzword or is it seen as a more viable medium for storytelling?

I think the biggest thing is that it is a buzzword. When people see it for the first time there's a wow factor about it. I think we have to be careful. We have to have enough entertainment value and enough content out there for people so it's an ongoing and growing part of people's daily lives. We go to the airport and see everybody heads down on their cellphones and laptops, and everybody spends hours online. Will this fit into that? It's all going to depend on compelling content.