Selfies are shifting our definition of beauty

"Snapchat dysmorphia" makes people want to look like an edited version of themselves.

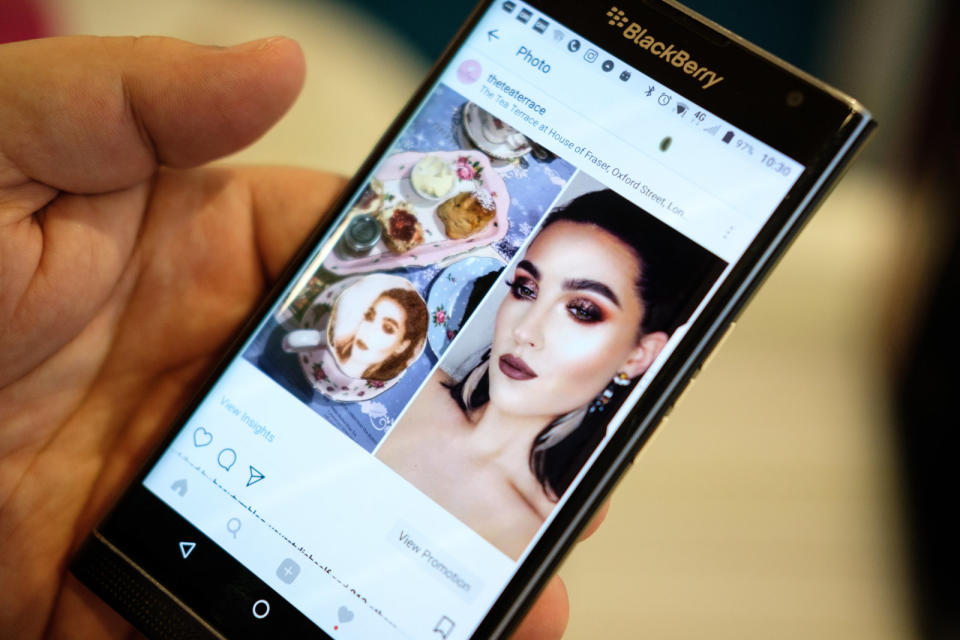

Selin Pesmes says she uses selfie filters because they smooth out her skin and present a "better-quality version" of herself. That's likely the same thinking for the millions of other people who regularly post edited pictures of themselves on social media, which are often created using selfie-enhancing tech from apps like Instagram, Snapchat and FaceTune. While some of these filters are fun or creative (for example: They can give you dog or bunny ears), many of them are simply there to make you look prettier. With a quick swipe, they can get rid of blemishes, fix the nose you don't perceive as perfect or give you lips that resemble Kylie Jenner's expensive fillers. Some people love these selfie filters so much that they're going to plastic surgeons and asking for cosmetic procedures that'll make them look like a software-enhanced version of themselves.

This phenomenon, which has been dubbed as "Snapchat dysmorphia," is being described by doctors and researchers as a form of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Now, obviously, not everyone using these filters suffers from the condition, but it's just further evidence that what may seem like harmless software can have a seriously negative impact on a person's mental health. Those dealing with disorders like BDD, which causes people to obsess over what they view as defects or flaws in their appearance, are more prone to try and find ways to look like their filtered photos permanently. In extreme cases, they may even seek plastic surgery. But that's not something everybody can afford, and doctors can reject patients they deem mentally unstable. This can actually exacerbate existing mental-health issues, and lead to anxiety and depression.

According to research from the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS), 55 percent of surgeons reported seeing patients who wanted a procedure which would make them look better in selfies. That's an increase of 13 percent compared with 2016. But the most interesting part of this trend is that many of these patients are now showing up to consultations with a filtered picture of themselves, rather than, say, a photo of a celebrity to illustrate what they want to look like. "This is an alarming trend because those filtered selfies often present an unattainable look and are blurring the line of reality and fantasy for these patients," Neelam A. Vashi, a doctor at Boston University School of Medicine's department of dermatology, wrote in a recent article about the topic.

Pesmes, who is 18 years old and runs a beauty channel on YouTube, told Engadget she enjoys putting filters on her selfies because "who doesn't want to look flawless every once in a while?" She said that while she's never thought of permanently altering her appearance to resemble a Snapchat or Instagram filter, she may want to get lip fillers one day. "No one is perfect. We all have beautiful flaws we should embrace," Pesmes said. "But I know in order to start a brand and grow your audience, looking very seamless in a photo does catch a lot of attention you want as a YouTuber just starting out."

"In today's society it's almost like looking your most natural self won't get you the millions of followers, which is sad."

Not surprisingly, she said, any time she posts a picture with a filter it tends to get more likes than unedited ones. And because likes are incredibly valuable in her quest to build a career as a cosmetics vlogger on YouTube, she opts for a filter most of the time because she notices "a larger attention" to selfies that have been tweaked. "In today's society it's almost like looking your most natural self won't get you the millions of followers, which is sad," she said. "I had no idea people wanted to go that far [get plastic surgery]. Knowing what I know now, I do feel that I should practice what I preach. If this is how I look without filters and tunings then the world has to get used to it."

Dr. Patrick J. Byrne, a professor and director at the Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and board member for the AAFPRS, said patients influenced by Snapchat dysmorphia tend to be teenagers like Pesmes (though people in their 20s or 30s aren't exempt). The challenge for plastic surgeons, he said, is to know when to reject patients who come in asking for procedures that'll make them resemble their filtered selfies. Sometimes that might be because what they want isn't medically possible or the individual isn't mentally fit and may need psychiatric help for issues like body dysmorphic disorder.

"I don't want any of my professional work to encourage any human being to place an unnecessary, unhealthy emphasis on their own appearance," Dr. Byrne said. "We know as a society that our appearance is really, really important biologically and socially. [But] I wouldn't want my children to do that. Why would I want my patients to?"

With the Snapchat dysmorphia phenomenon being relatively new, there's not enough research to know how many people are being affected, according to Dr. Vashi. She said the best thing experts in the medical field can do for now is raise awareness and try come up with proper treatments. "If we have someone coming in with something we don't feel appropriate or it's unrealistic, then there [are] basic questions and red flags we can look [at]." Dr. Vashi said, before echoing Dr. Byrne's statement. "Our job as physicians [is] to be able to recognize it, be aware, and then maybe sometimes go that extra step to really decide whether a patient is appropriate for cosmetic surgery or if the appropriate treatment is a referral to psychiatry."

While software that can make anyone look better in pictures has existed for decades, products like Adobe's Photoshop are expensive and require a certain level of expertise to use. Apps like Snapchat and Instagram, however, put selfie-enhancing tech at the fingertips of hundreds of millions of users every day. Now all it takes is a couple of swipes with your finger to make you look like you belong on the cover of a magazine.

"We teach children how to cross the street. We teach people how to drive before they get driver's license. Social media is another part of our world that needs to be learned."

Still, tech companies like Instagram, Snap or FaceTune aren't completely to blame for this trend, said Karen North, a clinical professor of communication at USC Annenberg who's an expert on social media and psychology. She said while they've helped amplify people's body dysmorphic disorders, it's unreasonable to hold them responsible when someone wants to have surgery. Just because you enjoy putting filters on your selfie, she said, doesn't mean you suffer from BDD -- though she did acknowledge that these features can act as a trigger for more serious issues on those who do have it.

Kaylee Kruzan, a Ph.D. candidate at Cornell University's Social Media Lab, also said it's important to know that social media isn't exacerbating mental health problems. Instead, she said, the issue is that these tools can be "particularly detrimental for individuals who are already susceptible to body dissatisfaction or have poor body regard," through constant examination of their appearance.

One of the biggest problems with social media, North added, is that it has made it so easy for people to compare themselves to their friends or followers. So, if someone uses a certain glamorous filter on a selfie to make them look like a supermodel, others are going to want to replicate that effect. "We teach children how to cross the street. We teach people how to drive before they get driver's license," she said. "Social media is another part of our world that needs to be learned. We need to teach people that the images they see on social media are not necessarily legitimate or authentic images of the people in your life. Don't compare your daily life to the image that other people post that's manipulated for the sake of social media."

Snapchat dysmorphia shows yet another dark side of social media. But it also shows that as technologies become ubiquitous (for example: photo-editing apps) we'll have to tackle new mental-health challenges that couldn't have been imagined before.