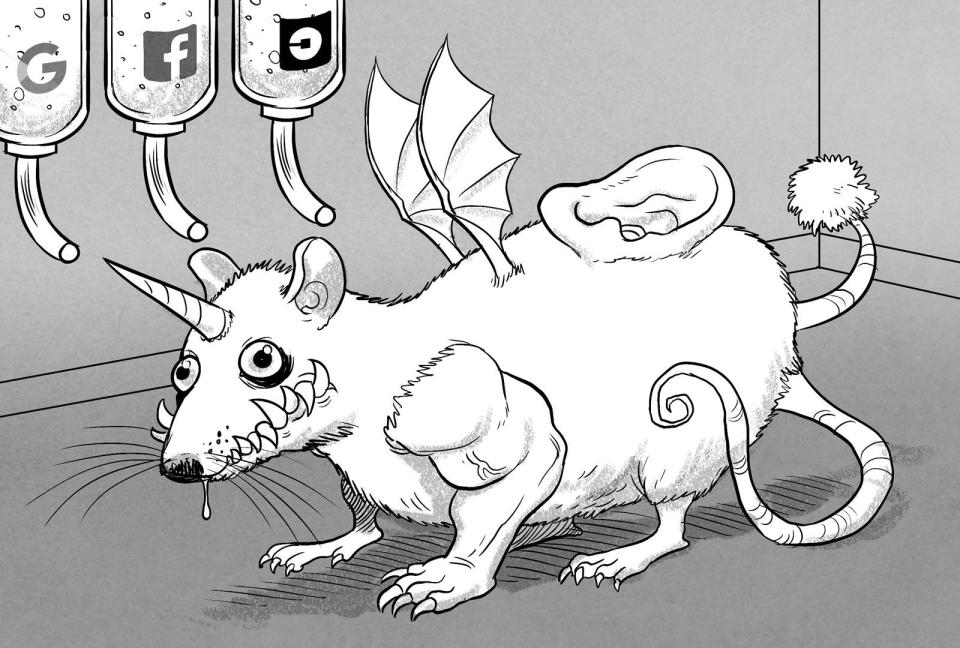

Uber, Google, Facebook: Your experiments have gone too far

Aren’t there, like, laws about testing on animals?

It was 2014, around the time when Travis Kalanick referred to Uber as his chick-magnet "Boober" in a GQ article, that I'd realized congestion in San Francisco had gone insane. Before there was Uber, getting across town took about ten minutes by car and there was nowhere to park, ever. With Boober in play, there was parking in places there never were spaces, but the streets were so jammed with empty, one-person "gig economy" cars circling, sitting in bus zones, mowing down bicyclists whilst fussing with their phones, still endlessly going nowhere, alone, that walking across the city was faster.

To be fair, you wouldn't know there were 5,700 more vehicles a day on our roads if you'd just moved here. Nor if you were pouring Uber-delivered champagne over yourself in a tub of stock options while complaining about San Francisco's homeless from the comfort of your company-rental Airbnb where artists or Mexican families once lived. But as usual, I digress.

So, witness my surprise face at a city study released this week confirming that Uber and Lyft have "caused a bigger headache on San Francisco streets than population and job growth combined," reported Streetsblog SF.

Locals, like me, no doubt also wore the same face of grim non-surprise while reading this week's news about Google's scary driverless car experiments on our streets. Back in 2011, according to The New Yorker, then-Google engineer Anthony Levandowski took a Waymo car onto a local freeway (where it wasn't supposed to be) and caused another car to "pinwheel" in traffic. Levandowski's co-worker later needed multiple surgeries after the alleged accident. The New Yorker reported that the engineers simply left the other car behind.

That was at the same time Google+ kicked a lot of people off its service -- and in some instances, outed them -- over its "real names" policy. Same as with Facebook's "real names" cleansing and outings, SF Bay Area's LGBTQ communities were disproportionately impacted by this policy. All I'm saying is, companies like Google seem to have a dangerous disconnect from those of us in the world outside their confines.

Anyway, the Waymo incident specifically illustrates something we would be wise to understand about the people forcing their worldviews on us. The New Yorker detailed:

They didn't go back to check on the other driver or to see if anyone else had been hurt. Neither they nor other Google executives made inquiries with the authorities ...

Levandowski, rather than being cowed by the incident, later defended it as an invaluable source of data, an opportunity to learn how to avoid similar mistakes. He sent colleagues an email with video of the near-collision. Its subject line was "Prius vs. Camry." (Google refused to show [The New Yorker] a copy of the video or to divulge the exact date and location of the incident.) He remained in his leadership role and continued taking cars on non-official routes.

According to the article, there were "more than a dozen accidents, at least three of which were serious." In an email statement Tuesday, provided after Ars Technica declined Google/Waymo's request to talk off the record, the company's spokesperson Johnny Luu wrote: "As to the report itself, we disagree with The New Yorker's characterization of the events dubbed 'Prius vs Camry.'"

The news outlet added, "When Ars specifically asked what Waymo disagreed with, Luu did not answer directly."

"The New Yorker declined to provide us with a list of incidents they were referring to, including the report of three serious crashes," Luu emailed to Ars. "On our end, we have always abided by all reporting requirements, including those covering regular car accidents, as well as the CA DMV regulations on autonomous testing that went into effect in 2014."

But even by 2013, San Francisco's streets were clogged with Ubers and Lyfts, as well as Google's mapping cars and Uber's self-driving car experiments, which they refused to get permits for until forced. Add to that fleets of private luxury techie commuter buses from Apple, Facebook, and especially Google, which all turned quiet neighborhoods into freeways, blocked regular buses, and used city infrastructure without compensating the city. This was the year San Franciscans took to the streets to protest the "Google buses" and physically block them, ranging from the use of colorful costumes to smashed windows and slashed tires.

Of course, in tech's latest experiment on the people of San Francisco, the city became littered with electric scooters — which were used in a recent "Google bus" protest in May. Sick of companies prizing quick VC cash over the sanctity of locals' lives, residents piled scooters in front of a private bus. There were so many scooters dumped on our streets, the scooters were removed from the bus's path as quickly as locals piled them back on. Like some recursive loop of tech's insularity to the people around it, its reckless indifference, forcing our neighborhoods and communities to fit the shape of their desires.

We could've told you who these companies were from the beginning, before it got bad, the way it is now. I'm pretty sure we've been trying. From our angle, all they've been doing is harm locals to get what they want.

Form an image in your mind from the May protest, when San Franciscans held up signs that said "your disruption is our displacement" as they blocked traffic. Now consider the class action lawsuit pending in an Oakland, California federal court and unsealed this week in which advertising companies allege Facebook willfully inflated and misreported video numbers — as high as 900% over actual metrics. (Facebook told The Wall Street Journal the allegations were "false.")

The thrust of the lawsuit's complaint states that when Facebook admitted to press a (much, much smaller 60-80%) overestimation of video viewing numbers in September-August 2016, the company claimed it had just learned of the issue — yet the complaint claims Facebook knew the numbers were wrong (in Facebook's extreme favor) since at least January 2015. The same year the company began telling press brands at the Guardian Changing Media Summit 2015 that text was dead, video was the future, and media companies better get with it or lose out.

Consider this in light of the fact that by 2016, Facebook had gone all-in on a persuasion campaign to advertising and journalism outlets insisting that the company was seeing an undeniable shift in online media from text to video — and that video consumption was exploding. Facebook execs, and even Zuckerbeg himself, throughout early 2016 parroted the line "Five years to all video" reports Nieman Journalism Lab while asking the question, Did Facebook's faulty data push news publishers to make terrible decisions on video?

The indisputable answer in Nieman's research and findings is yes. "Publishers' "pivot to video" was driven largely by a belief that if Facebook was seeing users, in massive numbers, shift to video from text, the trend must be real," Nieman wrote.

I think any longtime San Franciscan could've told you what would happen next. 2017 saw media outlets laying off writers in droves (like Vice, Mic, and Mashable) to go all-in on video. Which led to a rude awakening at the end of 2017, when according to Digiday and Comscore, "the publishers that pivoted to video this summer have seen at least a 60 percent drop in their traffic in August compared to the same period from a year ago."

As us San Franciscans have watched company execs cash in on rising property values and subsequently make our neighbors and schoolteachers homeless, we are not surprised to read about Uber strangling our streets, Google's (alleged) car wrecks for neat data, or Facebook (no stranger to evicting locals) destroying an industry for ad dollars.

So on both a local and global scale, I think that after this week, "your disruption is our displacement" is the understatement of our times.