Does the video game industry need E3?

Gaming's biggest show could learn a thing or two from indies and Twitch.

E3 is not a place for us."

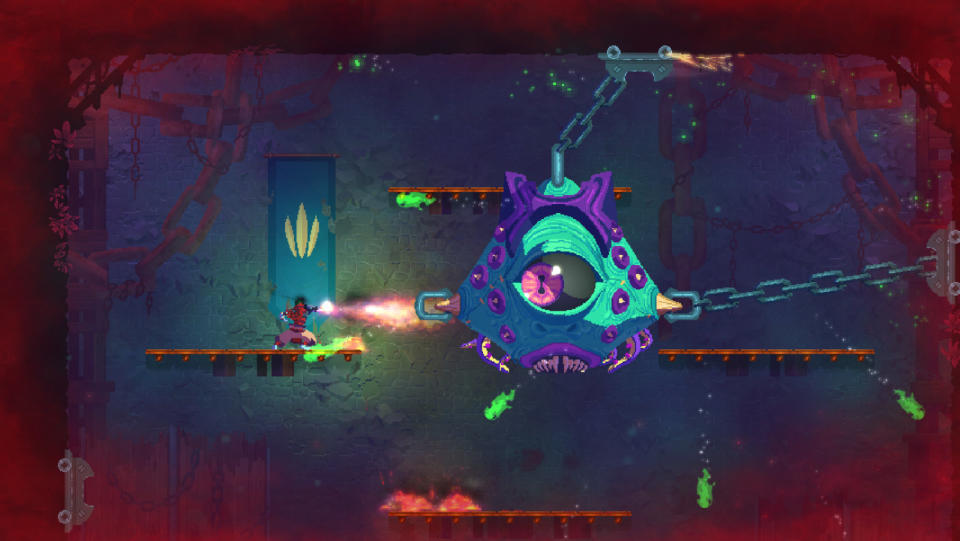

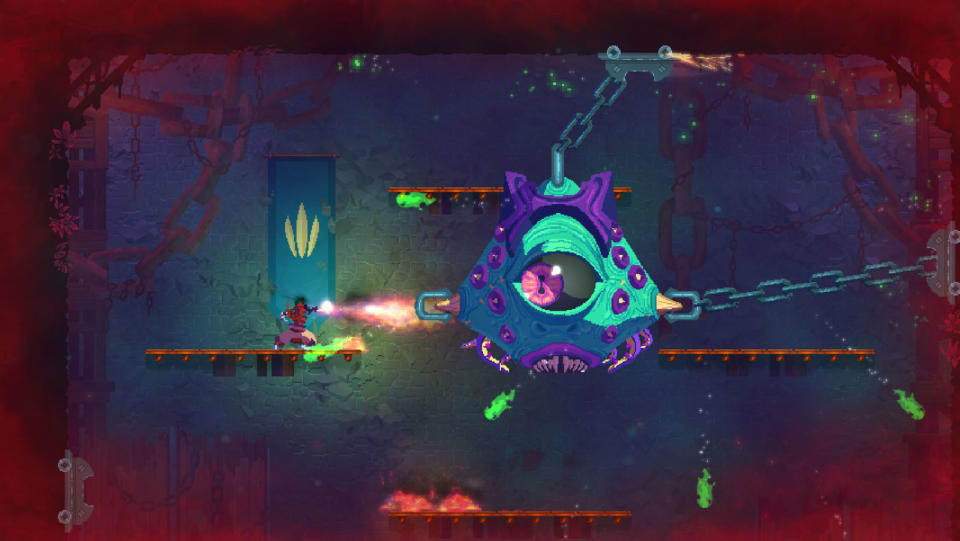

Steve Filby handles marketing for Motion Twin, the studio behind Dead Cells, and he's been building and shipping games for the past six years. Dead Cells is one of the hottest independent titles around, following a wildly successful stint on Steam Early Access, where the studio sold more than 730,000 copies in just one year -- before the game was technically finished. It's a bright and sprawling roguelike reminiscent of Castlevania, and since officially launching in August, it's picked up a handful of accolades, including two nominations at the 2018 Game Awards.

Dead Cells did all of this without exhibiting at the Electronic Entertainment Expo, or E3, the video game industry's most publicized trade show.

"The thing with E3 is that it's really a AAA event," Filby said. "It's not something that makes any kind of sense for an indie developer, even a larger indie like us, to be a part of. There's just too much noise."

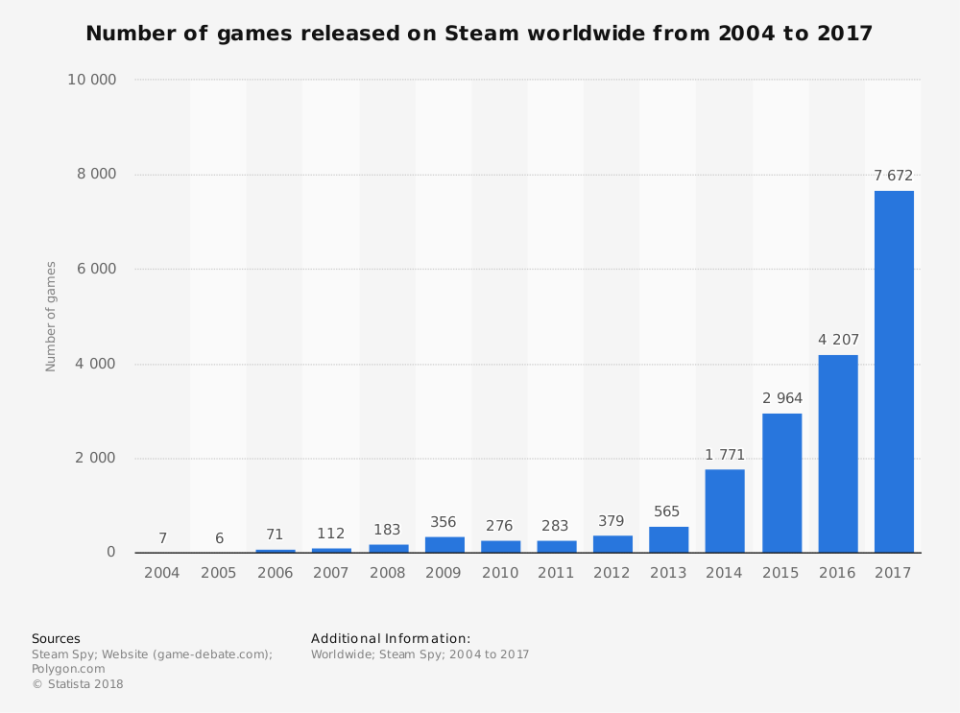

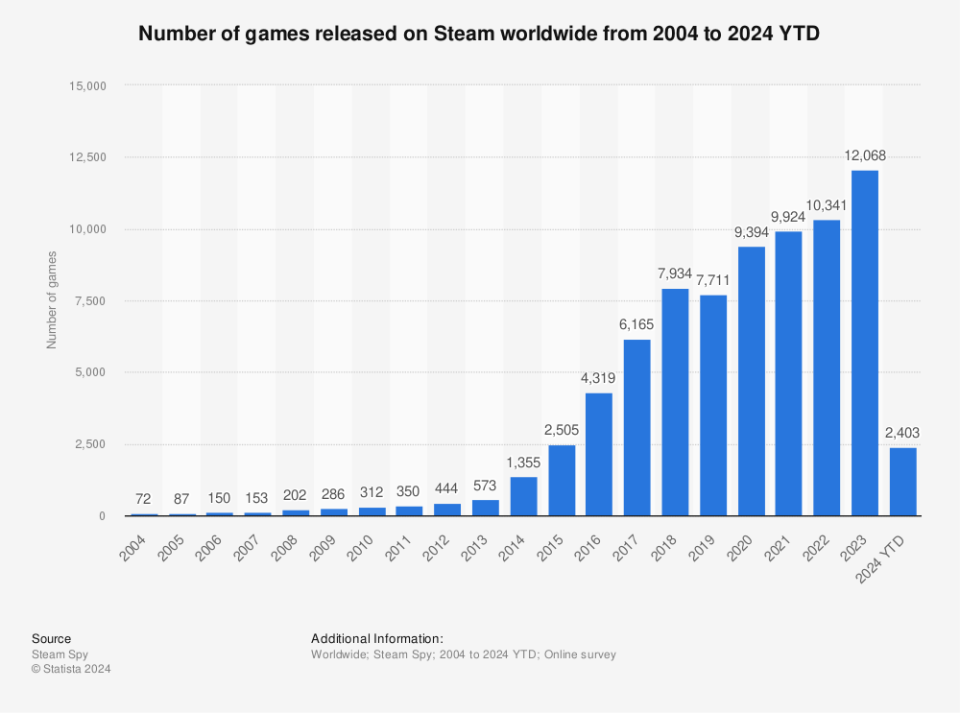

Filby isn't alone in his assessment of E3. The show has long been inaccessible for independent developers and even AA studios, with some of the largest booths costing upwards of $10 million to construct and display on the main floor. The Entertainment Software Association is the trade organization behind E3, and it's supported by 35 dues-paying companies, including Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo, Tencent, Activision Blizzard, Epic Games and Electronic Arts. Indie developers don't have a dedicated spokesperson within the ESA, though this community represents a swiftly growing segment of the industry. Just look at Steam: In 2004, it added seven total games to its digital store (according to Statista). In 2012, it added 379. In 2017, Steam added 7,672 games, many of which came from independent developers and small studios.

Companies like Microsoft and Sony showcase a selection of independent games during their big press conferences each year, and groups like IndieCade gather smaller studios on the show floor, but indie representation at E3 has not kept up with the growth of the industry. That's because E3 wasn't built for scrappy teams with high hopes and low funds; it was created in 1995 to rival the Consumer Electronics Show. The independent industry was essentially nonexistent (it didn't blossom until 2008 or so), and E3's purpose was to present the biggest companies in the flashiest manner possible, generating media attention and helping publishers negotiate with retailers like GameStop or Best Buy. The more E3 hype a game had, the better deal it could get.

"Everything there is disproportionate: the booths, the parties, the events, etc.," said Cyrille Imbert, CEO of Dotemu, the studio behind recent rereleases of Wonder Boy, Windjammers and other adored retro games. He's attended multiple E3s, but mainly for networking purposes, rather than exhibiting a game on the floor. "When you are there, you realize how big and crazy this industry has become.... Seeing the thing you're the most passionate about being so big and recognized is somewhat satisfying. But at the same time, it's very far from what we do, and, sometimes, I feel it's too much and doesn't really make sense. It's a lot about who is the biggest, rather than who can show the most creativity."

Twenty-three years on, E3 is still a AAA-focused event, but the retail industry has shifted dramatically. Digital storefronts and instant downloads are the norm, and physical stores are no longer a major artery for video game sales. Self-published indie games have inundated consoles, smartphones and PCs, while live streaming and influencer culture has become an essential aspect of any marketing plan.

Tentpole companies including EA, Nintendo and, most recently, Sony, have pulled back from E3, instead publishing pre-recorded videos and hosting their own conferences near the Los Angeles Convention Center during the show.

"Once thousands of creators could go sell their game on Steam or the App Store, all of a sudden you could be a successful creator with no need for physical distribution, commercial retailers, a publisher or the big expensive marketing cost of a show like E3," said Stephanie Tinsley, founder of Tinsley PR. She handles marketing for Devolver Digital and other indies. "All of that combined with the rise of fan shows like PAX [which happens four times a year], PSX and TwitchCon, not to mention retailers throwing their own events like the GameStop Managers Show, and what you can accomplish by working with the incredibly far-reaching influencers and content creators on Twitch and YouTube -- all of a sudden the millions of dollars budgeted for a show like E3 starts to make a little less sense."

E3 is bleeding companies while trying to navigate a digital-first ecosystem with '90s-era retail sensibilities. Its most recent solution to remain relevant and solvent was to open E3 to the public -- in 2017, the ESA started selling tickets to fans who wanted to experience the show firsthand. More than 68,000 people showed up at the LACC that year, making it the largest E3 on record. The move received swift criticism from many industry veterans, who complained of massive crowds and a divergence from the show's core purpose. Just two years later, Sony announced it wouldn't appear at the next E3 at all.

With more than two decades of shows under its belt, this isn't E3's first identity crisis. Hell, it isn't even the second. The show has rebranded a few times and bounced among a few locations, including a few years spent in Atlanta, Georgia. In 2007 and 2008, E3 was held in Santa Monica as the "E3 Media and Business Summit"; it was closed to bloggers and anyone outside of the core industry and involved a lot of PowerPoint presentations. Attendance dropped to just 5,000 people in 2008.

E3 returned to its original, ostentatious format at the LACC the following year, and attendance shot back up to 41,000. In 2018, E3's second year as a public event, the show drew 69,000 attendees.

"It's always been a bit perplexing trying to imagine how the show is 'worth it'"

"Several of us have been in the industry since E3 began, and honestly it's always been a bit perplexing trying to imagine how the show is 'worth it' to huge brands like Sony, Nintendo, Microsoft, EA, Steam, Apple, etc., who spend millions each year to, I don't know, remind industry people and press that they exist and are huge?" said Mike Wilson, co-founder of Devolver Digital. "Last year the energy did seem down a bit, at least for our industry friends who wandered over. They seemed largely beaten down by the fan factor."

Devolver has a rocky history with the ESA and E3, in particular. It's a high-profile indie publishing label responsible for games including Hotline Miami, The Talos Principle, Reigns, The Red Strings Club and dozens of other successful titles. Devolver has never purchased E3 floor space, but for the past few years it's hosted a multi-day party during the big show in a parking lot directly across the street from the LACC. They bring in Airstream trailers packed with indie developers and their games, set up a bar, bring in a food truck and settle in for a good time.

Devolver claims the ESA has attempted to thwart its party by blocking the parking lot with big trucks and generally making the planning stages as difficult as possible. The ESA doesn't make any money off of Devolver's E3-adjacent Airstreams, after all, a fact that Wilson has pointed to as motivation for the group's alleged ire. In response, Devolver has upped the ante: For the past two years, it's also hosted spoof press conferences mocking the E3 presentations of major companies like Microsoft and Sony (while providing a platform to advertise its own games, of course).

"It's a family reunion slash company picnic for us and our developers every year, many of whom travel there just to hang out with the posse even if they don't have a game to show," Wilson said. "As for our press conferences, it's just a convenient date to televise the magic with a lot of people watching, and if the big companies weren't there to set up our comedy with their super exciting conferences, there would be no need for ours, and no context for the humor."

Devolver represents the modern era of digital distribution and independent development, and its antagonistic relationship with E3 serves as a perfect metaphor. As a trade show, E3 is stuck in a behemoth, slow-moving, retail-focused rut, while the marketing and distribution worlds have evolved rapidly around it. Indie developers, Twitch streamers, Instagram influencers and digital distributors have more power than ever, and they're proving they can rival major companies like Sony and EA on the public stage.

"It's a celebration of the unsustainable nature of that whole scene."

So much so, that Sony is taking a page out of Devolver's book and skipping E3 next year. However, there's still plenty of hope for the ESA: Other major publishers (including Nintendo and Microsoft) are scheduled to come back with big booths on the show floor in 2019. The year after should be a big one for the video game industry overall, with speculation that the next Xbox and PlayStation hardware will land then, and E3 could once again bounce back from the brink of irrelevance.

One thing is certain, though. If E3 doesn't evolve in a major way, indie developers will remain on the outside, looking in. And eventually, there may be no one left inside.

"It's always kind of been a celebration of the big end of town; it's a place for the AAA people to go and party and hang out," Dead Cells' marketing man Steve Filby said. "Last year when I was there, outside of the events that I was invited to that were indie focused, I realized that I knew pretty much no one. It dawned on me then that it's really a place for the biggest of the big to duke it out, so in some ways it's a celebration of the unsustainable nature of that whole scene."