The story of the Duke, the Xbox pad that existed because it had to

The much-maligned, sometimes-loved controller is making a comeback.

Denise Chaudhari had never touched a gamepad before stepping onto Microsoft's campus as a contractor. The first woman to join the Xbox team, Chaudhari had studied ergonomics and industrial design at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design but didn't have any experience with joysticks. That's part of why Xbox's Jim Stewart was so excited to bring her on board: Her ideas wouldn't be based on preconceived notions of what a gamepad had to be.

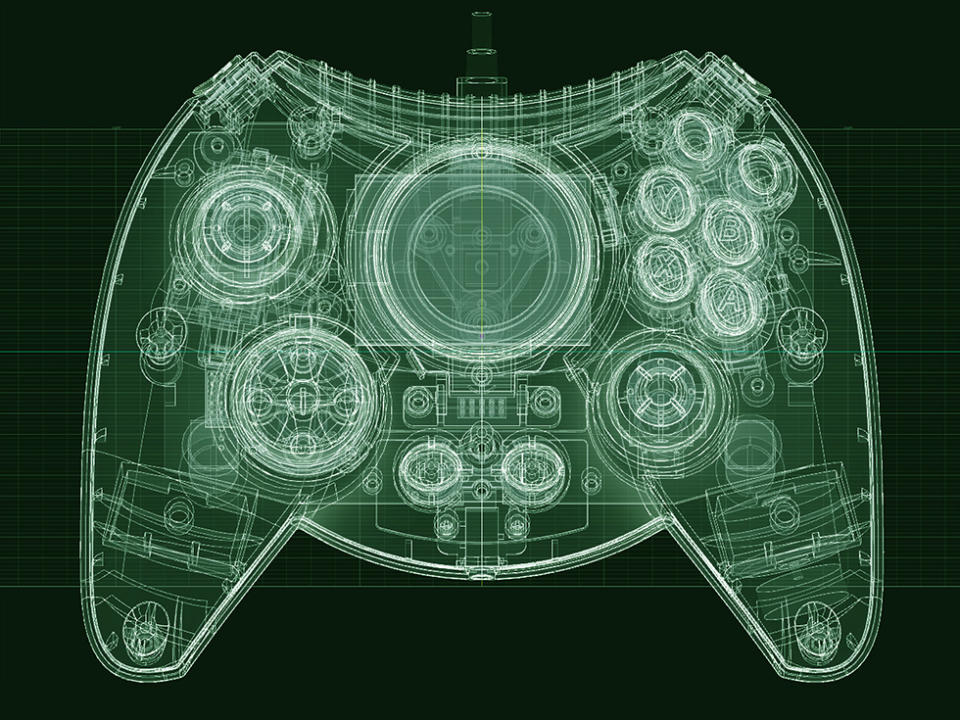

It was early 2000, and the company was preparing to enter the gaming world with the Xbox. In Nov. 2001, the console was released in North America alongside the Duke, a controller that seemed comically large compared to its contemporaries. Within a year, the oversize gamepad was abandoned by Microsoft and replaced with a smaller model, but the Duke has had an impact on every controller since.

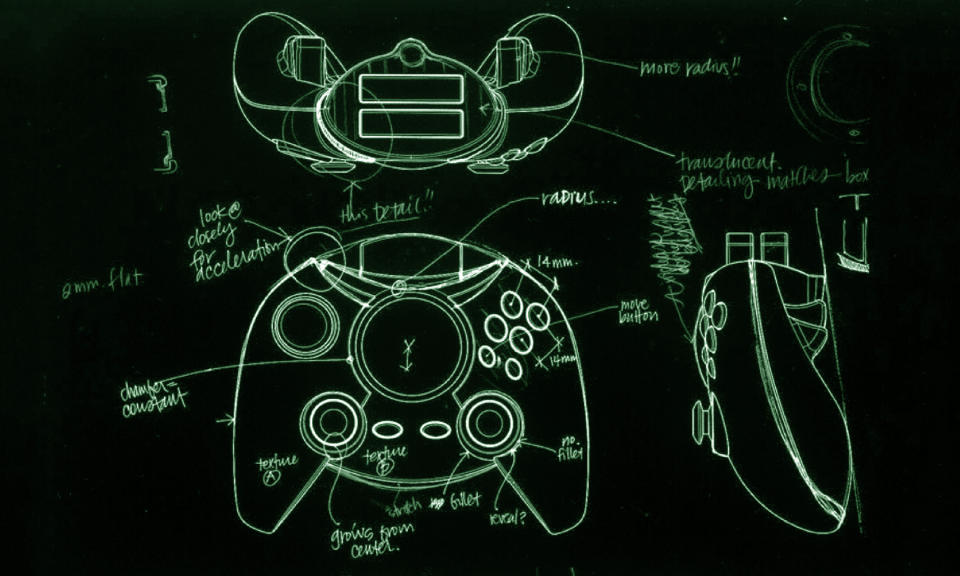

Rather than starting from scratch, Chaudhari had to work from Xbox creative director Horace Luke's concept sketches. They'd already been approved from up top, and a third-party supplier had built circuit boards based on those early drawings. Instead of coming up with the shape and ergonomics first and figuring out how to fit the device's internals into the shell after, Chaudhari needed to work backward.

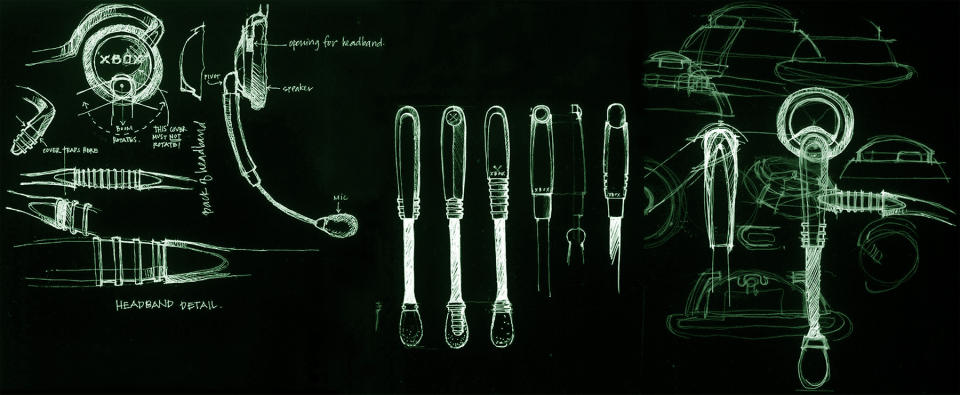

She got to work, sculpting physical models with a wood-like modeling material called RenShape. You can see the legacy of Chaudhari's work in every Xbox gamepad that followed. Its A, B, X, Y face button layout and button style remain today, for starters. But it's the thumbstick placement that has made the most lasting impression on controller design. While the DualShock had parallel sticks at the bottom of the controller, the Duke's were offset, with the left sitting higher than the right by about two inches.

It wasn't until her conversations with Xbox architect Seamus Blackley, J Allard (the "father" of the console's follow-up, the Xbox 360) and her now ex-husband Rob Wyatt that Chaudhari realized the hand she'd been dealt: The circuit boards, already manufactured and ready to go, were comically oversized.

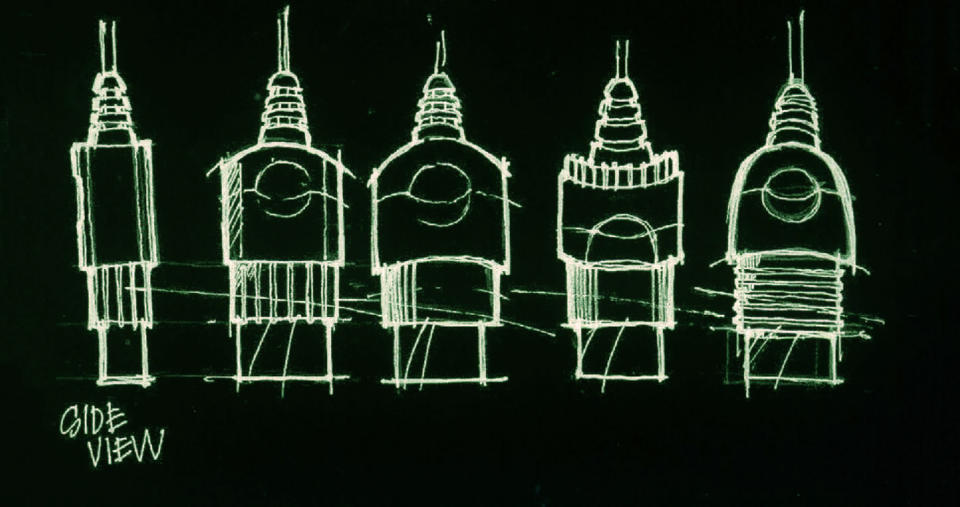

A large circuit board does two things. For one, it costs more to make. It also occupies more physical space. Looking over photos of the circuit board, longtime hardware hacker Ben Heck estimated that even in 2000, the board could've "easily" been a third smaller. He theorized that the circuit board's size was a necessity given the Duke's expansion slots for memory cards and an Xbox Live chat headset (also designed by Chaudhari).

"We were up against a wall," Chaudhari said. "The best thing we could do was create a case that was ergonomically comfortable. If it's gonna have to be that big, then it can at least feel good, right?" Case in point, the Duke's analog sticks are offset rather than parallel, positioned where your thumbs naturally rest.

"It was no secret to us that it was big."

According to Blackley, that decision was the result of a few Tony Hawk Pro Skater players on the team who thought it'd make virtual skateboarding more fun. Combined with developer Bungie's Halo: Combat Evolved as a launch title, the placement also helped make first-person shooters feel like a natural fit for a console, which was laughable up to that point.

Chaudhari spent most of her days working with electrical engineers, negotiating button layouts and placements, and generally doing whatever possible to shrink the gargantuan gamepad down to size, millimeters at a time. Blackley would come into her office almost daily to check her progress on the new prototypes. Each time, his reaction was the same: The controller wasn't small enough. Her immediate response never changed. She wanted to know how it felt in his hands. "And Seamus would say, 'It feels great, but it's huge,'" she recalled. "It was no secret to us that it was big." The final product was nearly three times larger than the PlayStation's DualShock controller.

At one point, the design team met with electronics supplier Mitsumi, which made the circuit boards for the DualShock. One of the reasons Sony's gamepads were so much smaller was because they used a two-part board that connected via a ribbon cable. The separate pieces of silicon sat perpendicular to one another and allowed for a more modest design overall. When Chaudhari asked Mitsumi if Xbox could have a similar-style board, she was flat-out refused, presumably because of Japan's nationalistic culture. "The takeaway was kind of like, 'Sony is a Japanese company; Mitsumi is a Japanese company. Xbox is an American company, and you don't get what you get because you want it, even if you're willing to pay for it,'" she said.

Microsoft loves bragging about how much time it spends with gamers listening to their wants and needs for consoles. It's why Xbox gamepads had nine-foot cables with in-line breakaways, for instance, while the DualShock's was a one-piece 6.5-foot cord. But focus testing shouldn't inform every aspect of design. "If you let gamers design a console, it would have built-in pyrotechnics and a machine gun," Blackley said. He quickly added that he didn't mean that as any disrespect -- he considers himself a gamer and understands the mentality.

"Nobody at the time could possibly have asked for a broadband, hard-drive-enabled machine that works with an operating system so it can provide services in parallel with playing a game that are helpful and good for online gameplay," he said. Same goes for easy game-development tools. "All of that stuff, intangibles, it's not something you would get by interviewing gamers. It's patent bullshit."

Somehow, while Microsoft was studying people's living rooms, it never took notice of how big the gamepads for competing consoles were or thought about how the console would be perceived outside the US. That domestic focus testing was top brass' justification for the Duke's size. Every time Blackley and his team would complain, they were told that people loved how big the gamepad was and that the design wouldn't change. "You can prove whatever you want in consumer tests," Blackley said.

Microsoft Japan was a different case. While American gamers were split between loving and hating the Duke, Eastern testers and developers unilaterally despised it. In the run-up to launch, Chaudhari and her team went to Japan to do some local focus testing. Before the trip, Chaudhari had heard Microsoft Japan was threatening to tell Eastern developers not to make games for the console unless the controller went through serious design revisions. "They were telling us, 'We have no choice. We have to tell developers that this is no good,'" she recalled.

"We have no choice. We have to tell developers that this is no good."

There was a catch to the testing though: The Americans weren't allowed to talk to or interact with the gamers directly. The worry was that once the testers saw Americans, they'd "know this is not really to be taken seriously, because it's not a Japanese product," she said. Instead, the Xbox team had to watch the sessions through closed circuit TV.

The tests were naturally conducted in Japanese, and because they didn't speak the language, the team had to rely on a Japanese Microsoft employee to translate. The wrinkle is that this translator had already told Chaudhari that he hated the controller. As an industrial designer, Chaudhari wanted to know if the buttons were close enough together or if the handles fit in the testers' mitts, details that she could use to adjust the design. Instead, she was told the testers didn't like anything about the Duke whatsoever. It wasn't helpful. She described the trip as one long Lost in Translation moment, where minutes of speech from the testers was boiled down to, "Oh, he doesn't like it; it's too big."

Did she trust that the translator was accurately relaying the feedback to her? "Of course not," she said. "It was really very pointless." The hardware had to go into production regardless of what the focus testing revealed, and so it did, with the caveat that there would be an immediate redesign for the staggered Japanese launch.

Blackley's interactions with Japanese developers were similar. Images of the Duke began appearing in magazines and online, and the game makers started to "freak out" because they were imagining telling their native customers that if they wanted to play the next Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest, they'd need this massive console and gamepad in their diminutive living spaces. The general worry among developers was that no one would buy their games and it'd damage their reputations. "There was actually a petition of Japanese game developers [against the Duke], and it had a lot of really famous names on it," Blackley recalled.

On Nov. 15th, 2001, the Xbox hit store shelves in North America with Chaudhari's Duke packed in. Three months later, it arrived in Japan with the svelte Controller S, designed by Microsoft's on-staff industrial designers. Once they saw it, people all over the world naturally wanted the smaller gamepad, and that fall, Microsoft made it the default controller that shipped with every console.

Suddenly, the Controller S was roughly two-thirds of the Duke's size because it used the two-piece circuit board Chaudhari had asked for initially. Other changes included the black-and-white face buttons being awkwardly moved away from the A, B, X, Y six-pack on the Duke's upper right side, and the Back and Start buttons shifted positions and changed design as well. The gamepad also finally had a traditional cross-type D-pad rather than the Duke's squishy wave style that felt like a leftover from one of Microsoft's SideWinder controllers for PCs.

"It was very easy for [Microsoft's designers] to be like, 'See? Told you so. If we had designed it, it would've been a hit right from the beginning,'" Chaudhari said. "They were really proud that they had vindication, that they could design a controller and that my original controller was discontinued."

"They were really proud that they had vindication, that they could design a controller and that my original controller was discontinued."

At the time, Chaudhari thought the Duke's legacy would be "shame." Microsoft was quick to throw her work under the bus, killing the Duke wholesale a few short years after making the Controller S the Xbox's pack-in gamepad. "It was this shameful thing that happened, that we launched a controller before we should have. We should have taken more time, we should've pushed harder for a different board. We should've waited and not launched when we did," she said, a hint of forlornness in her voice. Chaudhari said that there wasn't a jovial or congratulatory atmosphere surrounding the Xbox team's efforts after launch.

She's still incredibly proud of her work and doesn't consider it a black mark on her resume, regardless of the duress. In fact, it's quite the opposite. "It was probably the highlight of all the things I've worked on in my career," she said, "and there's been a lot." She said clients for her design firm are typically excited about her work on Xbox.

To this day, Blackley has nothing but praise for Chaudhari's talents. "She did a remarkable job making this thing that people love so much, given that it had to be the size of the island of Manhattan," he said.

For Chris Gallizzi, the Duke calls a different memory to mind. "It always reminds me of Xbox Live," he said. Gallizzi is a project manager and head of research and development at Hyperkin, the accessory maker bringing the Duke back to life. To him, it's intrinsically tied to his first foray into online gaming, and the gamepad's sheer size is what made the original Xbox as a whole so memorable. He speculated that if the console had shipped with a smaller controller that it wouldn't have stood out nearly as much. When he first saw the Duke, he was enamored by the translucent jelly bean-style face buttons and the massive Xbox nameplate in the center of the controller.

"I'm like, 'Wow! That controller must be so powerful for it to be so big,'" he recalled. "Then I grow up and find out that, no, there's actually no reason [for the size]. The designer was just working with what she had." He thought the gamepad was OK at the time but didn't particularly love it. These days, though, he likes the Xbox One gamepad so much that he uses an adapter so he doesn't have to play with a DualShock 4 when he's using his PlayStation 4.

Gallizzi first approached Microsoft about reissuing the Duke two or three years ago. Instead of an Xbox One controller, though, he pitched it as an accessory for the original Xbox. Hyperkin specializes in retro products for classic consoles, and while Gallizzi admits the Xbox is far from a classic, it was still a project he wanted to tackle.

Microsoft turned him down. Gallizzi was told that if Hyperkin was going to be a licensed partner, it should instead make accessories for the Xbox One. Fast-forward to early 2017 when Gallizzi got a phone call from Xbox's licensing director, Gaylon Blank. Blank said he thought he'd "paved the way" for the project to happen and asked if Gallizzi was still interested in working on the Duke. "Without checking with my bosses, I said yes," Gallizzi said.

After initial meetings with Microsoft, Gallizzi met with Blackley. Through a lot of what Blackley described as "good faith efforts," the trio worked out an agreement for Redmond to grant access to the original Xbox logo, boot animation and the Duke's industrial-design licenses.

Gallizzi and Blackley live a few minutes away from each other in Southern California, and over the next year they worked in secret to resurrect the gamepad. Between Feb. and June 2017, Gallizzi said Microsoft was largely quiet and he wasn't sure what was going on, but he and Blackley kept plugging away regardless. The weekend before E3 in June, he and a coworker were building prototypes on Gallizzi's balcony. The pair were under the assumption that Microsoft would debut the controller at E3 alongside its announcement that games from the original Xbox would be backwards compatible on the Xbox One. That never panned out.

That's not to say Microsoft hasn't played an active role in the Duke reissue's development. In fact, the company's participation was more intense than Gallizzi was used to with Samsung. After E3, things started moving quickly, and Microsoft began asking for progress reports more often and became very involved in general, asking for new rendering models on a weekly basis.

The internal design team wasn't happy, and even though the new Duke was being made by a third party, because of the licensing agreement, Microsoft had final approval on every aspect. Like where the shoulder buttons had to be shoehorned in, because now as an Xbox One controller, it had to have the exact same inputs as a standard gamepad. "I don't know how many samples we sent them for testing," Gallizzi admitted. Once both teams came to terms on overall design, Microsoft started kvetching about the gamepad's weight. The original Duke tips the scale at 425 grams; Hyperkin's version weighs 419 grams -- lighter by about the weight of a US quarter.

When the project started, Blackley gave Gallizzi a quick way to gauge how accurate the mock-ups were: The Xbox architect told him to put a dinner plate in his lap. If Gallizzi could replicate that feeling with his Duke reissue, Hyperkin did its job. By the end, Gallizzi wasn't prepared for how Blackley would measure success when he walked into Hyperkin's offices. "He didn't plug it in; he didn't play with it. He just put it in his lap," Gallizzi said. "He's like, 'That's all I need to know.'" Gallizzi was puzzled but said if Blackley was happy, so was he.

For the first six months, Gallizzi worked under the assumption that his version of the controller would be wireless -- a feature Microsoft had introduced with the Xbox 360 in 2005. But then Microsoft changed its mind, because no third-party controller is allowed access to the company's proprietary wireless technology.

"I pulled some shit to force Microsoft into allowing us to have the display,"

Hyperkin also toyed with the idea of repurposing the expansion slots as USB ports, but that ultimately didn't past muster either. The black-and-white face buttons, however, remain intact, acting as redundancies if you don't like the new shoulder-button placement near the triggers. An approximation of the terrible D-pad from the original controller is present as well. And instead of an in-line breakaway, Hyperkin's Duke mates to the Xbox One or a PC with a Micro USB cable that connects to the controller like a cellphone charger.

The new Duke's standout feature is an OLED screen that replaces the Red-Bull-can-size jewel from the original gamepad. Blackley wanted a killer feature that'd help the new Duke stand out from other third-party controllers. The display is something that he always wished the gamepad had back in 2001, in part because of his love for the Sega Dreamcast's VMU, a memory card with an LCD that slid into the console's controller. Gallizzi harvested LCD screens from cheap Chinese MP3 players for the prototypes he cobbled together on his balcony, while Blackley used OLED screens he had laying around at home.

To force Microsoft into approving the design idea, Blackley posted the infamous video of his work on Twitter. The video made headlines and racked up enough impressions that Xbox chief Phil Spencer direct messaged Blackley that night. "I pulled some shit to force Microsoft into allowing us to have the display," Blackley said. Anytime you press the button, the Xbox's boot animation plays, in tribute to the console's legacy.

It's this type of grit that defines the Duke's legacy today, Chaudhari said. Where once it was "shame," now it's "Seamus."

"There's only one person who could resurrect [the Duke], relaunch it as nostalgic and get away with it," she said. "And that person is Seamus Blackley."

It's easy to improve the Duke -- Microsoft has been doing so for the past 16 years. But improving it wasn't the point this time. While Blackley isn't confident he and Hyperkin nailed the feel and placement of the shoulder buttons, he's pleased overall.

"I don't think anything is perfect," he said. "I don't think this exercise was about making the perfect Xbox controller. This is about making the perfect Duke for 2018."