Why is a celebrity personal-finance guru suing Facebook?

Because he's tired of being the face of crypto scams.

Martin Lewis is a British journalist, TV presenter and Ralph Nader-esque campaigner who has announced that he will sue Facebook for defamation. The consumer champion has seen his face co-opted by nefarious types who use his name (and brand) to sell cryptocurrency scams. These get-rich-quick ads are often posted on Facebook, and because the social network doesn't seem to have a handle on them, Lewis is taking the battle to court.

Lewis is the founder of MoneySavingExpert, a hugely influential UK site that advises people on the cheapest financial and commercial products. If you've ever read The Points Guy, then you've got a fair idea of what Lewis does, but with a focus on consumer credit and household bills. He regularly appears on Good Morning Britain, one of the UK's major morning shows and even has his own prime-time broadcast TV show. So, in the UK at least, he has cultivated a brand as an honest and serious champion of consumer rights.

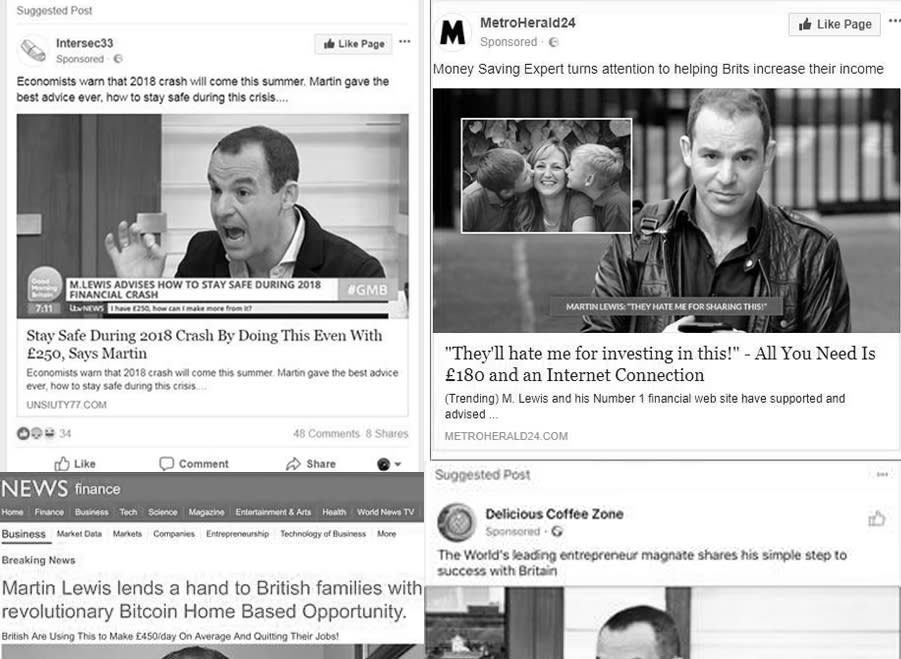

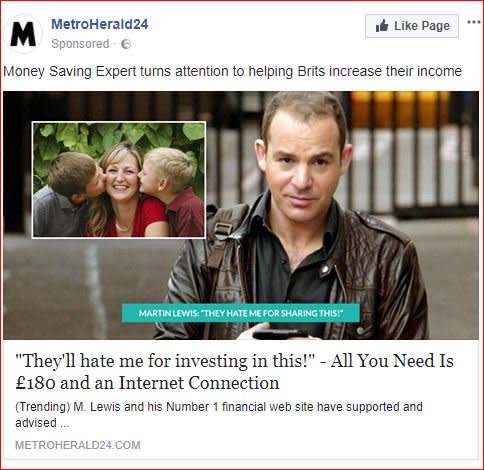

Which explains why so many crypto scams have harnessed his likeness to "sell Bitcoin from home" and "Increase your income!" scams. Often, as in the example images seen here (taken from Lewis' own statement), the scammers mock-up fake news pages from BBC News and other reputable news outlets. You may not be fooled, but others have been, and Lewis says that one individual was duped into spending £100,000 ($140,000) on such scams.

Lewis isn't the only person to become an unwilling spokesperson for scam adverts; Richard Branson has suffered a similar fate. We have seen adverts posted online that feature an image of the Virgin Group billionaire that has been photoshopped to make him look bloody. When you click through, it directs you to a fake-CNN page advertising a way for people to get rich quick with cryptocurrencies or binary trading investments. It is not clear if Branson took his criticism further or sought to shut down fraudulent uses of his image in another way.

You may, of course, be wondering how these adverts reach the eyeballs of most folks, and it's mostly down to self-service ad platforms. Essentially, anyone with a credit card can sign up to buy ads on the social network and can target them to specific groups of people. Put very, very simply, you can upload an image, set a target demographic and a budget for how much you're prepared to spend. It probably isn't hard to use a platform to target, say, vulnerable folks with professional-looking adverts.

Lewis is, however, targeting Facebook rather than the advertising individuals themselves, attempting to hold the social network accountable for what is published on its site. Because there is no telling how many people are behind the numerous scams, many of whom may be outside the UK, going after them all would be difficult. But Facebook, as the guardian of those adverts (and which likely profited from their publication) is potentially a better target for a lawsuit.

He has retained Mark Lewis, a famous British lawyer who has successfully fought landmark claims concerning phone hacking, as well as statements made on social media. In an interview with The Guardian, the solicitor said that the "adverts are in a lacuna of regulation." He added that "no newspaper would have run these adverts, and certainly not over 50 times." This case will, as usual, raise questions about if Facebook is a publisher, rather than a platform, a title it has fought hard to refuse.

In its terms of service, Facebook prohibits ads that infringe on a third party and those that contain misleading content. But the social network does not specify how it enforces or reviews the ads it broadcasts. The site does say that it reviews the adverts that are reviewed before they appear on the site, but that only raises questions as to what those moderators are looking for. Especially if they are giving ads like this a free pass:

Technology lawyer Neil Brown believes that the Martin Lewis lawsuit, "while not guaranteed to succeed, is not necessarily doomed to fail." He explained to Engadget that if Martin Lewis is to emerge from this battle victorious, he's going to have to swim against the generally accepted legal tides that have existed for years. It's a common principle that the platform holder, in this case Facebook, isn't responsible for the things its users publish on their pages. Certainly, before FOSTA-SESTA, the provisions for publishers and "platform holders," was seen as inviolate.

And in the UK, 2002's eCommerce directive essentially gave websites a free pass from civil or criminal liability. The only real exception to this is when the host was actually told about the problematic content it was hosting. In that instance, once it knows about violating media, the website needs to act "expeditiously to remove or disable access to the information."

These protections don't extend to companies that intervene in some way with the content that may alter things. Back in 2011, cosmetics brand L'Oreal sued eBay for allowing the sale of counterfeit makeup on its platform. EBay wanted to rely upon those protections, but a European Court found that because eBay had helped promote these listings, it was liable. It added that eBay should have been more proactive in looking to take down content that was potentially infringing.

In court, Facebook will also need to argue that it is not a publisher but a platform and that it is not necessarily operating within the UK's jurisdiction. All of which are knotty questions that will likely need to be answered in the country's superior courts, and may result in a European challenge.

In a statement to Engadget, Facebook said it "does not allow adverts which are misleading or false." It added that Lewis "should report any adverts that infringe his rights, and they will be removed." It goes on to say that Facebook is "in direct contact with his team, offering to help and promptly investigating their requests." Facebook's position is entirely legal within the scope of the 2002 directive, but the position may change in the future. After all, putting the onus on Martin Lewis, or any other individual, to monitor every instance that a fake advert uses their name, seems quite unreasonable.

In his statement, Lewis says that Facebook, which is a "leader in face and text recognition," should easily be able to weed out these scam ads. He added that "it's time that Facebook was made to take responsibility," because "nothing else has worked," and "people need protection." But if Lewis is hoping that Facebook will be told to clean up its act by monitoring every ad that it hosts, it might have some trouble.

The decision will also have ramifications for other companies that offer self-service ad platforms, like Yahoo*. Which has also been said to have similar issues with potentially questionable adverts, including ones featuring Richard Branson. In a statement, the company told us that it expects its "advertisers to comply with all laws, regulations and policies." An unnamed spokesperson added that the company "regularly take[s] action to block ads in violation of our policies, as well as bad actors who work to circumvent our human and automated controls."

Neil Brown explained that the case of Sabam v Netlog effectively lets companies like Facebook off the hook. Essentially, the Belgian musical copyright society wanted an ISP "install a filtering system to weed out electronic files for which the applicant claimed to hold copyright." But the European Court found that to do so would be to impose an unnecessary burden on a company.

Then again, that case took place in 2012, when Facebook wasn't yet considered the bête noire of the world. The company had just had a blockbuster IPO and had a billion users, but was still seen as a success story. With the increase in the company's financial and technical clout, plus its currently poor reputation, Facebook may find courts in 2018 aren't so forgiving.

*Yahoo is now part of Oath, Engadget's parent company.

Correction: This article originally claimed that Martin Lewis and Mark Lewis were no relation. They are, in fact, cousins.