To find a job, play these games

How AI is changing the hiring process.

I am trying to fill animated balloons with water without them bursting. I watch my laptop screen with laser focus, rapping the space bar as soon as a green dot appears. I weigh how much money to trade with an imaginary partner in a scenario akin to the prisoner's dilemma. This is all in service of finding me a job.

It hasn't just been me. This is the exact process that about a million applicants have followed to apply for positions at companies like Tesla, LinkedIn and Accenture. The platform that runs these games is Pymetrics, which somewhat whimsically dubs itself as a Hogwarts "sorting hat" for careers. The idea is that its games -- measuring 90 "cognitive, social and personality traits" -- provide more-objective markers of job compatibility than the traditional CV, cover letter and interview. If you're rejected from the position you wanted, the system can pair you off with what it deems a better match.

Measuring behavioral traits is a well-established recruitment tool, perhaps first encountered with high school RIASEC tests. Establishing these traits through games, however, is newer. The idea is that where applicants filling out a Myers-Briggs Type Indicator survey for a job might second-guess what the employer wants, their performance in a game doesn't lie or embellish.

"If I wanted to figure out how much you weigh, I could ask you," said Frida Polli, Pymetrics' CEO and co-founder. "You might not know. You might not want to tell me. You might have changed since the last time you got on the scale. But if I just put you on a scale, it's going to tell me."

Pymetrics makes custom algorithms for companies by running at least 50 of an organization's top performers through its games. This creates a model of an ideal employee to compare to applicants with similar traits. These games are particularly effective for standard entry or midlevel corporate positions as opposed to executives; Polli says the system can work for about 85 percent of jobs.

Unilever, for example, has used the software for an initial cull of applicants in its program for recent university graduates before moving them to the next stage of interviews and tests. Polli says they have doubled the number of applicants they hire after the final interview round.

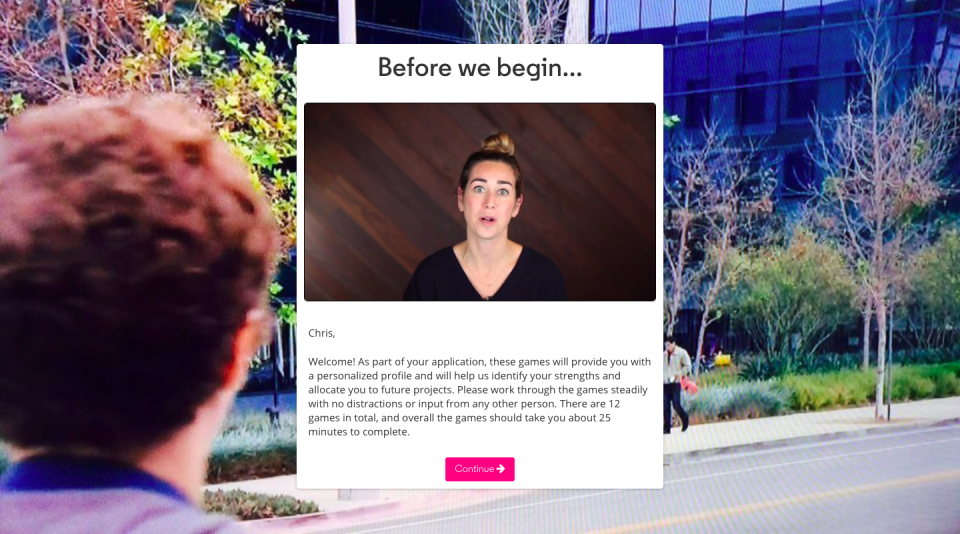

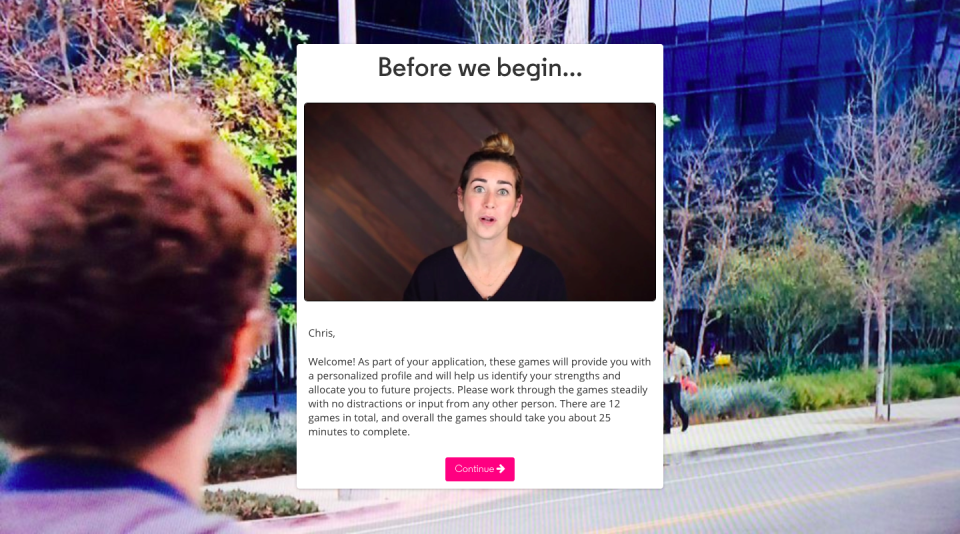

I access Pymetrics through my browser, and in a video intro, a woman who identifies herself as Lauren tells me I'll play 12 minigames, each taking no longer than a few minutes. "Most importantly, there are no right or wrong answers, so just focus on being yourself," she says. "And have fun."

The games themselves are simply animated and introduced with minimal explanation. It's not ambitious to guess what some of them might measure. In the money-exchange game, I suspect they're tracking my risk appetite and cooperation with others. Matching photos of faces to the correct emotions seems designed to test my empathy skills. I'm finished in half an hour and wait on my results.

Pymetrics is one of many examples of how data analytics and AI are augmenting the recruitment process.

There are other companies in psychometric testing like Australia-based Revelian and Arctic Shores in the UK. Applied, Textio and TalentSonar all help edit biased language from job listings as part of their services. Hirevue -- also used by Unilever -- conducts video interviews automatically analyzed for intonation and gestures, with no human interviewer necessary. According to a Deloitte report from 2017, 29 percent of global business leaders surveyed said they use games and simulations in hiring, although 71 percent of them rated their use of those techniques "weak."

"We have decades of research that [is] very clear that expert judgment is OK, but algorithms are better," said Nathan Kuncel, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota who studies predictors of work performance. His research has shown basic equations beating human hiring decisions by at least 25 percent.

When firms like Google receive millions of applications a year for several thousand openings, it's unsurprising that the average recruiter spends only six seconds scanning a CV. Meanwhile, interviews relying on the recruiter's intuitions are permeated with bias. "We tend to like other people who are just like us," said Kuncel. "[We] ignore everything else about them and their résumé and work history as a result. We like to confirm our initial impressions."

However, algorithms perform some functions less well. Pymetrics cannot measure "passion," Polli notes. Robin Erickson, a vice president at Bersin by Deloitte and co-author of its talent-acquisition report, has yet to see a measurement for career flexibility, "which is important given that most employees will have 12 or more jobs over their career," she said, citing the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

"In the model-building process, we weight and de-weight different trait inputs until all different gender and ethnicity groups have the same chance of matching to the model."

And in the same way Spotify tends to serve up more of the music you already listen to, data-driven hiring often works by replicating a company's existing setup, which is less helpful when organizations are trying to create a culture shift or hire an innovator. At worst, interviewer bias could be replaced by AI bias -- for instance, an algorithm preferring to hire men because data show that this demographic makes up the majority of current positions.

Pymetrics says its algorithms are carefully audited for bias. "In the model-building process, we weight and de-weight different trait inputs until all different gender and ethnicity groups have the same chance of matching to the model," said Priyanka Jain, the company's head of growth and lead product manager. "What we consider de-biased is based on the EEOC [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission] standard of the four-fifths rule, which basically guarantees that no one population is under or as likely to match as four-fifths of the population." Polli also tells me that Pymetrics' data doesn't go to any third parties. "The end user owns their data," she said.

The direction of the $200 billion recruitment market, experts say, is toward a kind of meta-analysis of everything that goes into job performance -- your testing, accomplishments, personality scores and interpersonal skills like charisma. While interviewers might overvalue their gut feelings about a candidate, they're also adept at noticing red flags which should be weighted and combined with quantitative tests. According to Elaine Orler, CEO and founder of consulting firm Talent Function, most of the Fortune 1000 companies she surveys use between eight and 15 different recruiting products.

An ideal platform would be a simulation of the job, says Richard Landers, associate professor of industrial-organizational psychology at Old Dominion University in Virginia.

"Where I think we're eventually moving is [to] some kind of virtual or augmented reality where you are observed at how well you can do the job without actually doing the job," he said. "A classic idiom in psychology is, 'the best predictor of future performance is past performance.'"

Some companies do trial runs as part of their hiring process, asking programmers to solve coding problems, for instance. Pymetrics, in a less job-specific way, uses these gamified dynamics, too. Yet if immersive technology allowed a full-replication of a gig for more than an afternoon, it could be the most accurate -- if onerous -- test of an applicant's abilities and traits, including their soft skills and drive. "If you can fake passion for a solid week, you can probably fake passion the whole time you work there," Landers said.

A few days after completing my tests, I speak with Pymetrics' Jain about my matches. It turns out I've passed the first hiring round for a management-consultant position at a top global firm, a human-resources employee at a multinational consumer-goods company and a fast-food chain worker at a franchise anyone in the US would recognize.

My efficiency at weeding out distractions while multitasking is apparently useful both for managing personnel and flipping burgers. That same trait would have gotten me rejected from a data-entry role at a global-analytics organization.

I fit roles in private equity but not software development. There were no journalist profiles in the system but even if there were, there's no guarantee I would have matched to it. (And while my testing process was similar to another applicant's, none of my details were actually submitted to the companies).

In one way, the experience strips down the idea of choosing a job to what it is: a capitalistic matchmaking of labor and employer. Fitting the optimal cogs in the optimal slots. That razor efficiency might pay little attention -- if one even has the privilege to seek it -- for what you want to do, perhaps out of a sense of social duty or personal meaning.

Besides, like reading a horoscope, my results seemed to only align with my self-conceptions when I looked at them from certain angles. I wouldn't trade my current job for some of these algorithmic suggestions.

Yet the entire point of these games is that our knowledge of self is notoriously limited. We don't necessarily know what we're good or bad at. We might spend over 90,000 hours of our lives working, yet enter our career paths randomly. We only take the options we can see.

Finding work is hard; attempting to locate the perfect vocation can be an existential crisis. If nothing else, this process presented me with a few new ideas about myself -- the kind of ideas that a career switcher or someone who's typically been marginalized from certain industries might make great use of -- and the first step towards actualizing them.

We don't quite have a careers "sorting hat" just yet. But we do have software that cracks the door of a couple more possibilities.