Roborace is still pursuing its driverless race-car dream

A demonstration at Goodwood showed how far the company has left to go.

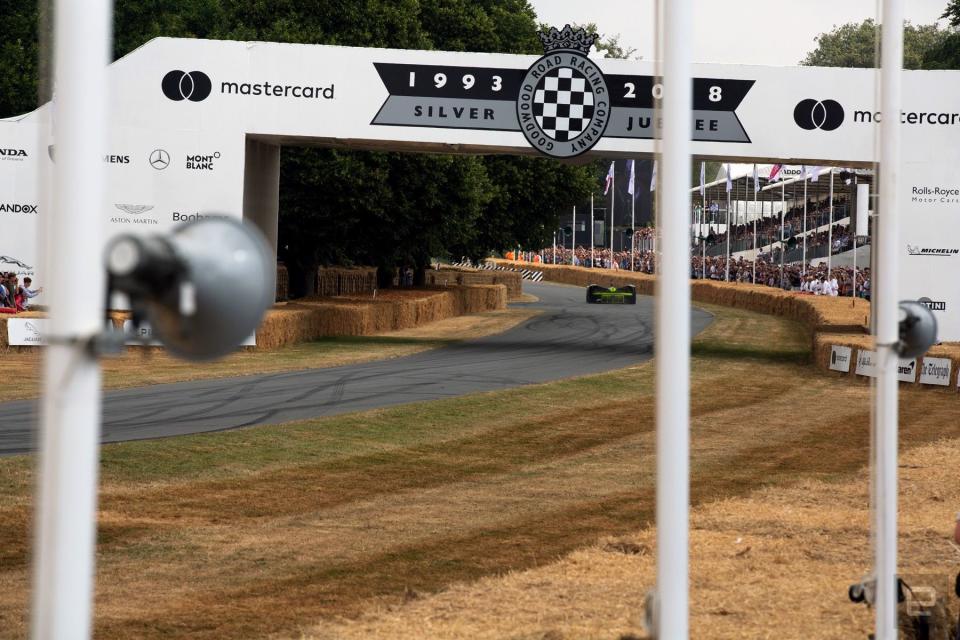

Clearly, Roborace doesn't believe in bad luck. Last week, on Friday the 13th, the company chose to run its self-driving Robocar in front of a feverish crowd at England's Goodwood Festival of Speed. It was only the second time the team had demonstrated its futuristic vehicle publicly, following an unassisted lap in Paris roughly 13 months ago.

There was no room for error.

The absence of a human cockpit gives the car an unusually low profile. Its delicate curves were drafted by Daniel Simon, a concept-vehicle designer who has contributed to science-fiction blockbusters including Tron: Legacy, Prometheus and Oblivion. The robot racer's shape resembles a Formula 1 car, the Batmobile and a heat-seeking missile mashed together.

The machine moved slowly, though, up the famous hill-climb course. Well, slowly compared with the other vehicles that had tackled the Goodwood track that day. Roborace had capped the car at 125 KMH (roughly 78 MPH) to ensure it completed the route safely. In the world of motorsport, that's pretty slow. The robot's racing line, too, was conservative. It stuck to the center of the road, leaving plenty of tarmac on either side as it both entered and exited each corner. Ayrton Senna da Silva, it was not.

Still, the drive was a milestone for the British startup. Thousands hugged the track-side hay bales and watched as the car zipped toward the finish line. In a little under two minutes, it had completed the course and returned to its dormant state. The Roborace team could breathe a sigh of relief.

Roborace, as its name subtly suggests, wants to host a Formula E-style racing championship with electric and fully autonomous race cars. Before the run, I asked Bryn Balcombe, chief strategy officer at Roborace, the two questions that are on everyone's minds: When will two Robocars go head-to-head? And when will we see a full starting grid? The driverless race car, after all, was first unveiled in February 2017, at Mobile World Congress. Almost 18 months later, it's not clear how far the company is from hosting its first real event.

"I think, technically, we're not far away," Balcombe said.

"Technically, we're not far away. I think it's a question of when is that moment, you know?"

For Roborace, the difficulty is knowing when the car and underlying software are ready. Clearly, the vehicle is capable of navigating a track on its own. But has it matured to a point where spectators will be impressed?

"That moment of two Robocars on a track," he explained, "it's on the list."

Roborace is tackling a number of problems in parallel. There's the car, of course, and the self-driving smarts that a host of Silicon Valley companies, including Tesla and Alphabet's Waymo, are trying to perfect for everyday use. In addition, the company is figuring out the best way to onboard teams. Roborace was conceived as a battle of autonomous intelligence; the company will supply the basic software, but then it's up to engineers to customize and improve the algorithms. That, in theory, will separate the competing cars and simultaneously improve self-driving technology for all.

Earlier this year, Roborace challenged two universities -- the Technical University of Munich and the University of Pisa -- to develop a faster car in Berlin. Both teams drove the Devbot, a test car with a cockpit, six times around a 2-kilometer track. The first three were with a human behind the wheel, and the final three were with software alone. The team with the fastest average lap was crowned the "Human and Machine Challenge" winner. "It was very interesting," Balcombe said, "because it was the first time we didn't use our software."

Robocars are expensive, so the company has to figure out how, if at all, it should be restricting new teams. The company would like to avoid engineers, after all, flipping the car on the first corner of every race. In Berlin, the two universities were forced to pass a makeshift driving test before they could race in a competitive environment. In traditional motorsport, drivers start in slower go-karts and earn licenses before competing in faster, more dangerous forms like Formula 1. Roborace is thinking about a similar licensing system for engineers who want their algorithms to compete in its competitions.

"At what level is this AI driver?" Balcombe said. "Is it near that go-karting starting point, or is it Formula 1 level? That's a big spread in capability."

The company is talking to cities, too, that might want to host one of its races. Roborace is pitching itself as the pinnacle of autonomous technology, which could appeal to mayors who want to show off their town's smart and connected credentials. Hosting a Roborace could also be an effective way to attract teams and, by extension, nurture local experts in the field. "There's a global competition at the moment for talent," Balcombe said, "and if you can showcase that your city is the best place to develop this technology then you kind of want an event to showcase that."

At the same time, Roborace needs to show up at public events and dazzle visitors to maintain interest.

Charging through chicanes is no easy task, however. Roborace spent six months preparing for its Goodwood hill climb. It involved some human reconnaissance and a practice run with the Devbot, which produced an accurate, three-dimensional map for the Robocar to reference.

The trees around the course meant that GPS wasn't an option. Roborace encountered a similar problem during a demonstration in Hong Kong last year. Densely-packed skyscrapers, known as street canyons, regularly block out parts of the sky. To compensate, the team had to develop an entirely new software platform based on LIDAR, the laser-based equivalent of radar (most self-driving cars use LIDAR to navigate and spot potential hazards on the road.)

"When the car left I thought, 'they've got that set too fast.'"

The solution Roborace developed in Hong Kong, though, is unable to differentiate grass and tarmac. To run the car at Goodwood, then, it needed a set of machine-vision cameras that could discern driveable surfaces and pipe this information into the mapping and navigation systems. Finally, the team set up a course at Magny-Cours in rural France that reflected the hill climb at Goodwood. Robocar was driven at speeds higher than 120 KMH -- the vehicle has reached 210 KMH (roughly 130 MPH) before in private testing -- but capped in southern England for safety reasons.

Before the demonstration on June 13th, Roborace conducted a practice run with the Robocar. "It was incredible really," Balcombe said. "I was standing at the start line and when the car left I thought, 'They've got that set too fast, surely they've got that set too fast.' The dust that it was kicking up, I was like 'Oh my God!'" It wasn't too fast, however. The car made it to the top of the course just fine, settling any remaining nerves about the public showcase.

For Goodwood, the Robocar was provocative. The concept is divisive for long-time motorsport fans that have grown up with fleshy, seemingly superhuman drivers and deafening gasoline engines. For Roborace, it was a chance to show off in front of a huge audience. "It was bigger than any of the Formula E events that we've done so far," Balcombe said.

The hill climb also showed the potential versatility of the Roborace competition. Unlike Formula 1, the motorsport could take place on different surfaces, and with various race types including point-to-point sprints. Above all, the competition is about testing each team's software. A mixture of challenges could add to the drama for viewers while improving the technology for more real-world scenarios.

That's important if the company is to win over critics who believe that motorsport requires human drivers. The challenge for Roborace is to demonstrate why autonomous cars deserve their own format, and that the teams behind each vehicle can be just as compelling as Lewis Hamilton.

To that end, Roborace has spoken with Yamaha executives about putting its motorcycle-riding Motobot against the Robocar. Normally, a Moto GP versus Formula 1 race would be highly dangerous, but with robots, it's a viable competition format. At this year's Goodwood Future Lab, Swedish startup Einride unveiled an autonomous logging truck called the T-Log. Balcombe suggested that larger vehicles could be placed on the track as believable traffic during each race. "There are lots of things we can look at to make this entertaining but relevant to the entire industry," he said.

Fast and the Furious-inspired street races? Highway chases with Burnout-style near misses? It's an exciting prospect for anyone who likes to watch explosive crashes and death-defying stunts. Right now, though, that dream is a long way off. The hill climb, while important for the company, highlights just how much work Roborace has to do. One commenter wrote scathingly on YouTube: "They forgot to program race mode. They should program at least drift mode. " Another said: "I'd rather watch the cleaning lady drag a Dyson up the driveway. " Despite summiting Goodwood, it feels like the team has barely reached base camp.