The kings of artisanal cheese wear lab coats

The Cellars at Jasper Hill focuses more on farming microbes than milking cows.

Forget France. In the 21st-century artisanal cheese world, all roads lead to the tiny town of Greensboro, Vermont, home to the Cellars at Jasper Hill.

There, brothers Mateo and Andy Kehler craft some of the best cheeses in the world: Jasper Hill has won at least one award from the American Cheese Society every year since 2013, as well as global recognition at the World Cheese Awards. Their ability to raise dairy cows, create cheeses and age other companies' products in their $5 million, 22,000-square-foot facility has made them role models for the 500 or so indie cheesemakers in the US.

"Jasper Hill is my favorite American cheesemaker," said Michaela Weitzer, the education coordinator at New York City's premiere cheese shop, Murray's Cheese, adding that the quality is impeccable and "insanely consistent."

With his wavy brown hair and calm voice, Mateo Kehler radiates a rugged hippie vibe. Get him talking about cheese and he turns exacting and profound, with aphorisms like "cheese is a discovery, not an invention" and tales of how new staff tend to develop a "romance with Bayley Hazen Blue," their signature product.

"We describe Bayley as a gateway blue," Mateo said, and it's not hard to see why. Though blue cheese is notoriously divisive, Bayley Hazen -- which is named for a historic road in the area -- is almost mild, and eating it akin to driving down creamy boulevards with notes of nutty cobblestones.

For centuries cheesemakers have relied on tradition and intuition to make their foods, and those customs are still the status quo, even in the new-school American artisan world. The self-taught brothers first made cheese in those ways too, but they soon realized they had tools at their hands: science and technology.

"I used to say that being a cheesemaker is like being God, except that you're blind and dumb," Kehler said. But with the use of 21st-century technology, he's modified his statement: "Being a cheesemaker is still like being God, still dumb, but at this point we can see."

For the past decade or so, the Kehlers have been researching every part of cheesemaking in order to improve upon those traditions, and their facility looks more like a laboratory than a medieval farm. They use the tagline "a taste of place," which is pretty much the definition of the word "terroir," the amalgamation of factors like soil and weather that give so many foods (like wine grapes) their particular flavor. In cheese, one of the major factors that separates your Trader Joe's Camembert from the award-sweeping variety is microbes.

What Is Terroir?

Wine aficionados have been using the word "terroir" for years, and recently other genres have adopted the term as well. But it's not just some jargon to make you sound like a snob at Chez Couteux.

Terroir means that things taste like where they're grown: It's the concept that the sum of the soil, microorganisms, landscape, and climate are integral to an ingredient's aroma and flavor. Wine grapes are the most famous example, but terroir applies to coffee beans, maple syrup and cheese.

The word "microbes" might once have brought to mind E. coli and salmonella, but in the past several years, our culture has begun to see these tiny organisms positively: Kombucha and kimchi now line the shelves of almost every grocery store, boasting probiotics to help bacteria grow in your gut.

Kehler, however, is focused on finding microbes that improve flavor. "I would say we milk cows," he quipped, "but we actually farm microbes."

In 2010, the Kehlers started looking at their cheese under a microscope. They'd been sampling their milk since 2003 and had quite a large store of data to research but were far from trained experts.

Enter Rachel Dutton, who The New York Times called "a go-to microbiologist" in 2012 for her work with culinary legends like David Chang and Harold McGee. She and Kehler met in 2009 through a cheese shop as she was finishing up her PhD in microbiology at Harvard. In 2010 Dutton and her colleague Benjamin Wolfe started working with Jasper Hill as part of a Bauer Fellowship at the Center for Systems Biology at Harvard, which gave her "five years of funding to run a research lab, completely devoted to studying cheese," she said.

"The driving framework for our research was to try and develop cheese to be a model system to study communities of microbes," she explained. "Even though cheese is much simpler than other microbiomes, like the gut or the ocean or the soil, it has this rich set of communities." In her first study, she and Wolfe collected samples of more than 160 different types of cheeses from 10 different countries.

How to Make Bayley Hazen Blue

Bayley Hazen Blue is one of the most complicated cheeses in the company's repertoire. After producing their own top-notch hay to feed their herds of cows, Jasper Hill employees carefully milk them, then culture the cheese. For Bayley Hazen, they add Penicillium roqueforti spores -- which eventually creates its blue veins -- and calf rennet, separate the curd from whey and shape the curds into a mold. The mold is sent to the cellars and salted, then aged for up to 90 days. Throughout those weeks, they pierce certain wheels in that batch of cheese multiple times to test for flavor development, among other things. This year they'll make about 200,000 pounds of Bayley Hazen, which retails for $34 per pound.

Home, though, was Greensboro. "I call Bayley our lab rat," Dutton said, noting that she's done the most research with this particular cheese. (Incidentally, it's also her favorite cheese, "for personal and professional reasons," she said.)

"Even though we're working with cheese, we're not really asking questions that are going to directly impact cheesemaking," she said. For example, Dutton's team has learned about how bacteria exchange DNA with each other, an effect you can see in antibiotic resistance.

As Dutton explores the way this model community functions, she's paving the way for scientists to understand more complicated communities like the gut -- or even outer space. Thus a recent article by Heather Paxson and Stefan Helmreich called "The perils and promises of microbial abundance: Novel natures and model ecosystems, from artisanal cheese to alien seas" about both artisan cheesemaking and "the speculative research of astrobiology." As many have long suspected, cheese might contain the answer to life itself.

Where scientists like Dutton see potential for understanding our world more completely, the Kehlers simply want to research microbial communities to make better and better cheese.

For example, when Dutton started working with Jasper Hill in 2010, everyone thought they'd discover more information about the commercial starter cultures Jasper Hill was using. But those were nowhere to be found. "What we did find was this crazy array of microbes that we weren't adding in," Kehler said. "When you plug them into databases, similar sequences that have been isolated from different environments around the world will pop up."

The most common were marine species that are often found "on arctic sea ice." Halomonas in particular loves salt, so it makes sense it would grow on a salt-covered food. Then there were outliers like a type of microbe typically found in Etruscan tombs. Yes, Etruscan tombs.

"These microbes are everywhere," Kehler said about why one might find remnants of a thousands-year-old Italian grave among your crackers and grapes. "The chemistry of a particular environment creates a selective pressure which supports the growth of certain microbes and suppresses others." Knowing this, Jasper Hill is able to cultivate the microbes they want and suppress those they don't.

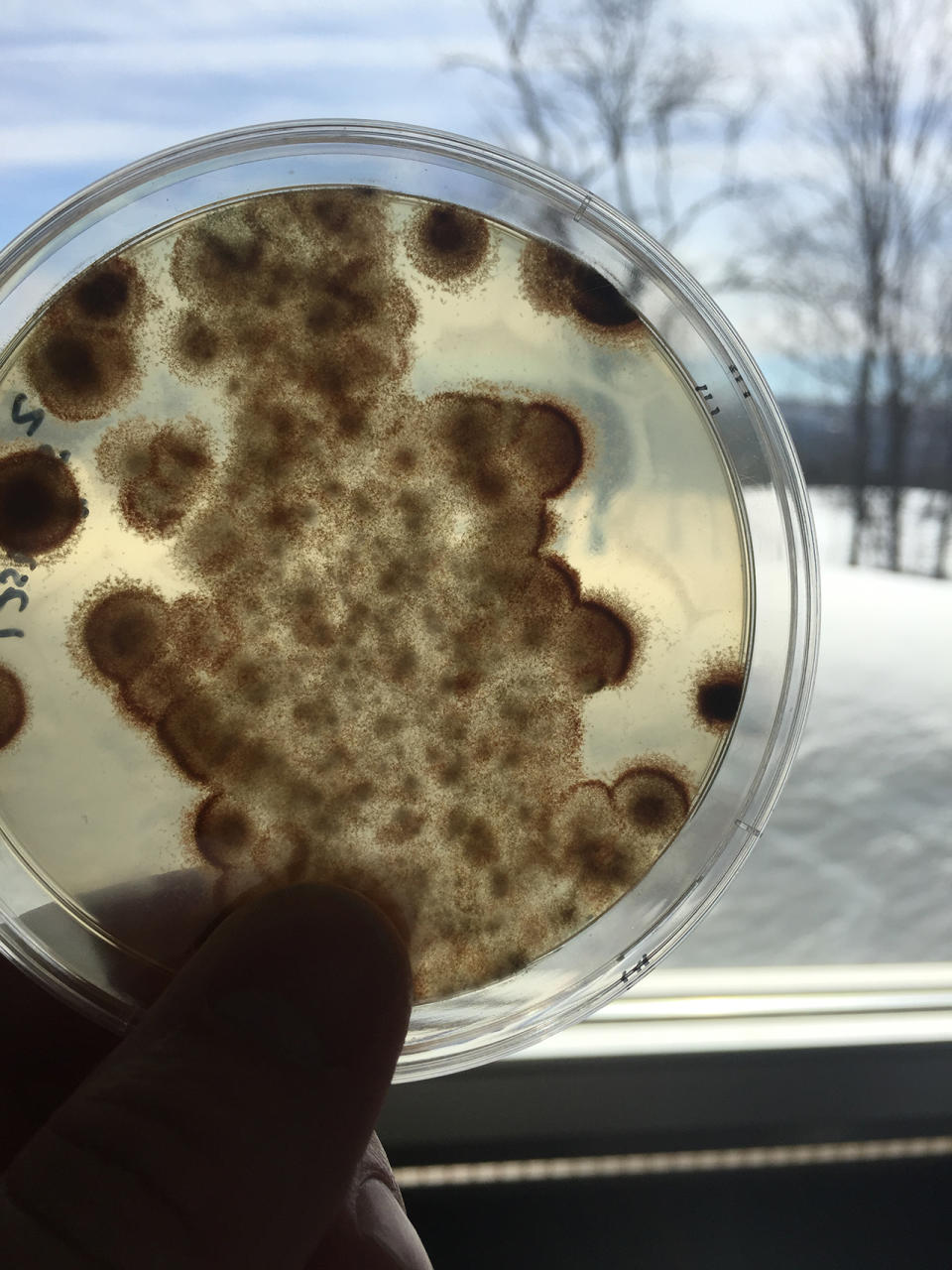

In 2013 the Kehlers created a designated lab with intense machines like an autoclave, laminar flood hood, and QPCR machine (essentially a sterilization tool, a clean space, and a fancy machine that breaks DNA strands apart and replicates parts of them) while employing a full-time microbiologist, part-time lab tech and a trained sensory panel.

In the lab, the team is growing lactic-acid bacteria and ripening microflora. When these elements are ready, they're combined in a mother culture and incorporated into a mini batch of soft cheese. "We've identified five or six interesting microbes that work synergistically and produce a lot of aroma," Kehler said, noting that his favorite is Brachybacterium, with its cauliflower and cabbage aromas. Other aromas from other microbes include Play-Doh, Concord grapes and Kraft American Singles.

"We have been primarily looking for microbes that produce sulfur notes, as these generally translate to flavor in cheese," Kehler said, noting that his favorite, Brachybacterium, is one of those rotten-egg types. They're also looking for functional attributes like how well families of microbes produce and consume acids, thereby changing the conditions of the surface of the cheese, the rind.

In total, Jasper Hill has a full genome sequence on 21 strains of bacteria that have Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status from the FDA, and they're identifying several more to sequence this year. The company uses some of them in its current production.

Of course, it's not as simple as "add Brachybacterium, get amazing cheese." Microbes form communities, and they behave differently depending on the other microbes around them. (Call it keeping up with the Joneses, microscopic style.) So Jasper Hill also measures "the composition of the ecology," as Kehler said. That way, if they change one thing (like the feed supply), they can track the effect it has on the rest of the process and the resulting cheese.

Translation: They keep really good records. They use two databases, Milk Man and Cave Man, to track everything from sensory data to whether the hoof trimmer was at the barn when the cows were milked. "Cheesemaking is an exercise in consciousness over time," Kehler said.

Lately the experiments at Jasper Hill have slowed. After more than 20 years in the US, the director of quality and food safety, Panos Lekkas, decided to apply for a green card. While his application was being reviewed, his H1B work visa expired, "leaving him in a special kind of limbo," said Kehler. That was months ago, and there still hasn't been much word.

Without the microbiologist's work, Jasper Hill can't make progress on its scientific discoveries, create new cheeses or tweak its current cheeses. Kehler said he's certain Lekkas' problems are "related to the Trump administration's war on immigration. We believe it's part of the racist, nationalist politics that are in vogue presently. It has been brutal for our business and very expensive."

For hundreds of years, place has been essential to taste. Within the cheese world, that has meant that legally, Parmigiano-Reggiano can only come from a specific region of Italy, Brie from a particular part of France, and manchego from one area in Spain.

Yet science challenges the primacy of place. In one experiment as part of Dutton's fellowship, she followed nine wheels of cheese for two months each to understand how the microbial systems in them developed, then reproduced that pattern in the lab to make a sterile Franken-Bayley. In other words, Dutton proved that the recipe you use -- microbes and all -- is more important than your location. "Technique is more determining than, say, climate," write Paxson and Helmreich.

With that finding, the landscape of artisan cheese has started to shift for a company like Kehler's, whose goal is to "develop a line of cheeses whose identity is linked to a place."

Kehler might hope that other Vermont-based cheesemakers start to use Jasper Hill's recipes, extending the wealth to the larger community. But a cheesemaker in Wisconsin could do the same thing, or big companies like Kraft could hijack the knowledge, blurring the line between artisan and commodity food. However, there's a big difference between reading the recipe for boeuf bourguignon, for example, and making it taste exactly like Jacques Pepin would: The "technique" Paxson mentioned is essential.

In the debate about place, American artisan cheesemakers tend to view terroir as more inclusive than their European counterparts. To them it means "the range of values -- agrarian, environmental, social, and gastronomic -- that they believe constitute their cheese and distinguish artisan from commodity production," writes Paxson in "Locating Value in Artisan Cheese: Reverse Engineering Terroir for New-World Landscapes."

"We're trying to shift the relationship ... so that the identity is with the cheese, not the cheesemaker," Kehler said. "Because on a mission basis, these cheeses have economic power. If we're able to create a market and these place-based products that can support the landscape here for generations to come, that's what we want to leave [for] our community."

After all, terroir has come to mean more than geographical location, cheese more than something you eat. Kehler recalled that when he and his brother invested in the land, they were "satisfying three fundamental needs: meaningful work, in a place that we love, with people that we love."

The Cellars at Jasper Hill, he said, are "our response to globalization," in that he and his team see their business as a way to put high-value products into a capitalist system in order to take cash from communities with disposable income and redistribute it to their own community. "The core of our business is this economic and community-development mission, and cheese is the way we're accomplishing that."

Cheese for the Kehlers is both the most important and least important thing. In fact, the scientists and cheesemakers alike are engaging with what Paxson and Helmreich call "model ecologies -- studies in how to frame the world." Cheeses can be a lesson in how microorganisms relate to one another -- or how they could or should relate to one another. Among the human community of Greensboro, Vermont, the Kehlers are considering the same thing.