NASA details the most distant world we've ever observed

It has published the first scientific paper on the Kuiper Belt object named Ultima Thule.

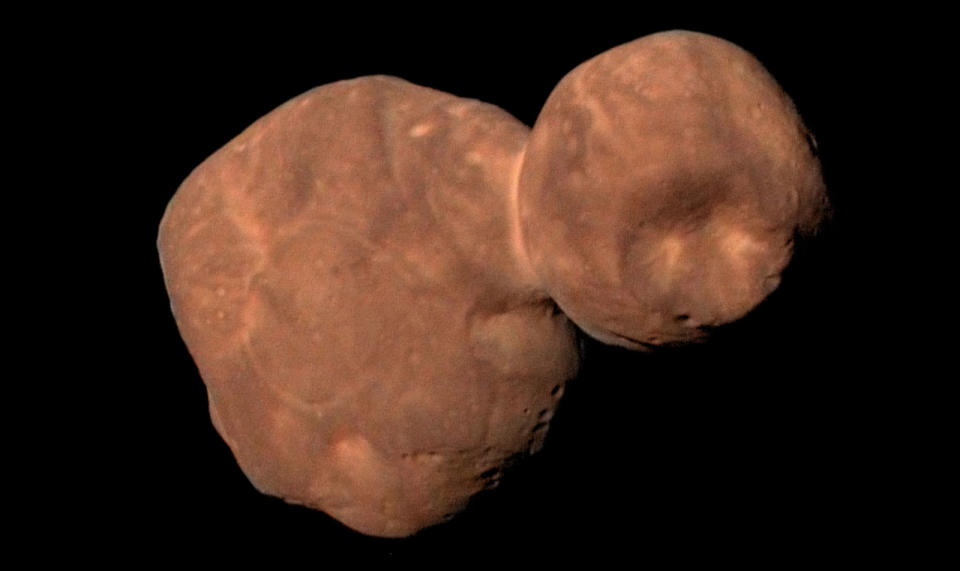

Back in February, NASA released the clearest images of Ultima Thule -- the Kuiper Belt object New Horizons got close to in a flyby, which makes it the farthest world we've ever explored. Now, the New Horizons team has published the first scientific results of the data the spacecraft beamed back, giving us more information on the ancient remnant of an era when our Solar System's planets were still in the midst of forming.

The paper, published in Science, contains information on the "planetesimal's" development, geology and composition. As NASA previously said, Ultima Thule has two lobes that make it look like snowman, though it's actually flattened like a pancake. Those two lobes appear to have formed close to one another before they became an orbiting pair that eventually merged. The larger lobe measures approximately 22 x 20 x 7 km, while the smaller one is around 14 x 14 x 10 km big.

In addition, Ultima Thule is very red in color. It's much redder than even Pluto and is actually the reddest object New Horizons has visited. While the team isn't 100 percent sure yet, they believe the redness is a result of the modification of the organic materials on its surface. The paper also notes that the object rotates on its axis every 15.92 hours and that its brightest regions are in its neck, where the lobes are connected. It has two bright spots inside its largest crater-like feature, as well.

Speaking of craters, Ultima Thule doesn't have a lot of small ones, which indicates that there aren't a lot of objects smaller than 1 kilometer (~3,000 feet) in diameter in the Kuiper Belt. The paper also said that New Horizons didn't find any evidence of satellites, rings or an atmosphere around the object. These are but the initial data from the flyby -- we're bound to learn more about the flat space snowman in the coming months. The New Horizons probe is still transmitting data from the event and will continue to do so until the summer of 2020.