The importance of Apple and Google’s rare collaboration on contact tracing

Privacy meets pandemic.

Go back to the dawn of 2020 and the notion of everyone downloading an app to track our encounters with other people would have been worrying if not absurd. Today, with cases of COVID-19 ballooning in the US, it’s becoming increasingly probable that this kind of surveillance will be a key component in restoring society to normalcy.

The proposal is to use our smartphones for digital contact tracing. In the journal Science, a key paper by University of Oxford researchers recommends the technique. Even the European Data Protection Supervisor has advocated for an EU-wide app. Meanwhile, after Singapore and South Korea used tracing apps as part of their strong response to the spread of COVID-19, governments in France and the UK (through its National Health Service) are developing their own tracing apps. And the head of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says the method is under “aggressive evaluation” as projects in the US sprout up from coast to coast.

The unprecedented collaboration on an interoperable infrastructure between Apple and Google — which came together in two weeks and was announced last Friday — has now set the stage for a robust, potentially global contact tracing system.

The idea of contact tracing is straightforward. When someone contracts a disease, public-health workers need to know who that person has had recent contact with to be able to locate, test and possibly isolate those contacts to stop the disease spreading even further.

For decades, this technique has required painstaking drudgery — interviewing patients about their every move, calling airlines and managers of restaurants, examining hotel records — to determine everyone that’s been exposed. This was the case in tracking the paths of HIV, Ebola and measles.

The challenge is that tracing each case typically takes many days. In Wuhan, China, more than 9,000 epidemiologists performed this task, working in teams of five, according to the WHO. Latest figures show there are about 83,000 cases of COVID-19 in China. In the US, there are currently tens of thousands of new known cases every day; a former CDC director has said the country would need “an army of 300,000 people” for effective contact tracing.

Right now, most of the US is under stay-at-home orders because we don’t know who has COVID-19 and who hasn’t; to be safe, we’re presuming that anybody could.

This is where digital stalking comes in. All that detective work could happen in an instant, using a tracking app. Anyone who has had contact with a patient— shared an elevator or office, bus or train — gets a message to instruct them on how to get tested. In one UK survey, about three in four respondents said they’d definitely or probably install this sort of app.

Right now, most of the US is under stay-at-home orders because we don’t know who has COVID-19 and who doesn’t; to be safe, we’re presuming that anybody could. In San Francisco and Massachusetts, local authorities are beefing up their contact-tracing capabilities, but for the most part, experts say, we’ve missed the boat on tracking the exact path of virus transmission for now.

However, effective tracing paired with widespread testing will be pivotal in containing COVID-19 after social distancing ends. For people to work and congregate again, we need to continuously identify and test people so they can be individually quarantined if they have contracted the virus. Knowing who does and doesn’t have it could allow us to separate the safe from the vulnerable, allowing society and the economy to gradually sputter back to life.

Here’s the first catch: For contact tracing to be effective, a lot of people need to opt in to tracking. David Bonsall, an Oxford researcher and co-author of the Science paper, has placed ‘a lot’ at about 60 percent of a country’s population. And while smartphone ownership in the US is just over 80 percent, the question is How do you get three quarters of the nation’s smartphones to all persistently share locations?

Enter Apple and Google. Unlike startups, NGOs and university initiatives, these companies already have a critical mass of users. With nothing but a software update, about 3 billion phones globally could have contact-tracing functionality.

Around now, alarm bells might start ringing. Consenting to this kind of global surveillance appears to fly in the face of everything we’ve learned about sound data hygiene. Trust in the technology industry was in decline before COVID-19. In a worst case scenario, privacy experts fear contact tracing could create the architecture for a more invasive surveillance state —and new norms that can’t be rolled back.

Consider that Google has hardly covered itself in glory when it comes to being honest about its use of our location. Separately, the US Department of Homeland Security has reportedly bought cellphone location information from private companies for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (aka ICE) to detect undocumented immigrants.

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, Israel has tapped cell phone data from its domestic intelligence agency to identify people potentially exposed to the virus. In Korea, mobile alerts broadcast information — which might include family name, age and recent locations — about nearby people who have COVID-19. In some areas of China, an opaque algorithm built into wallet app Alipay determines someone’s health risk, which in turn determines their ability to take public transport.

“There’s no question that civil liberties have to give way when it comes to a public health crisis like this, but any incursions on civil liberties have to be necessary, they have to be effective and they have to be proportional.”

The location-based data initiatives we’ve seen in the US so far have relied on aggregated, anonymized location data — the kind you might rely on in everyday apps like Google Maps — released by companies like Facebook, Google and Foursquare. The CDC and regional governments have also reportedly been using this data to see trends of where people congregate. But this data doesn't give away individual locations.

“There’s no question that civil liberties have to give way when it comes to a public health crisis like this,” said Jay Stanley, a Senior Policy Analyst at the ACLU's Speech, Privacy and Technology Project. “But any incursions on civil liberties have to be necessary, they have to be effective and they have to be proportional.”

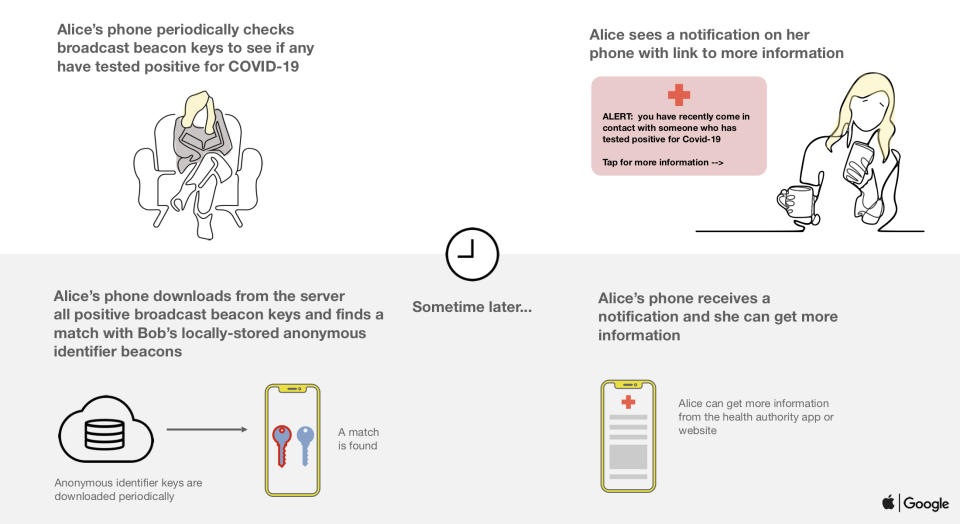

With GPS location data considered too revealing, the safe solution that projects like COVID Watch and the Pan-European Privacy Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT) have been pushing for uses Bluetooth. The system would have every opted-in phone regularly emit anonymous beacons via Bluetooth. Other phones in the vicinity receive and store those unique beacons — which frequently change — and emit their own. This creates a record of two phones in proximity to each other, but only known by the two phones.

Should one person later test positive for COVID-19, a health official could ask the patient to send their records to a server that broadcasts to other phones and alert any phone whose records indicate they’ve recently encountered a person with the virus, perhaps encouraging them to get tested.

Based on the details so far — more are still forthcoming — this is, for the most part, the system Apple and Google have thrown their weight behind.

First, they will introduce an interoperable API on both Android and iOS for Bluetooth-based contact tracing on public-health apps. This should be ready by mid-May. Then, they’ll add their own contact-tracing functionality into their respective operating systems. But this is months away and would still require a public-health app for a full range of functions.

There are some potential downsides to Bluetooth — it doesn’t track transmission of the virus via surfaces (the reason we’re all sterilizing our deliveries) and could create false positives, depending on the range of a phone’s Bluetooth signal and the amount of time apps determine you need to be close to someone to register an encounter.

But from a privacy perspective, the key idea is that there will be no recording of where you were or when. The only thing you know is whether you’ve encountered someone who tested positive in the last 14 days, and there would be no revelation of who that person was. It would be opt-in only and minimize the data that goes to a central server. Apple and Google say they cannot see users’ encounters and have published early technical specifications for scrutiny online. The fact that the two major smartphone giants have built this architecture means that every NGO, academic and government health department is now incentivized to work within it.

What version are you on?

One issue not addressed in Google's announcement of the partnership is Android-version support. The company has long had a problem with Android-version fragmentation; because manufacturers each have their own quirks when it comes to customization and support, billions of Android devices, globally, run thousands of slightly different software configurations. While a source of annoyance to both developers and users, though, this hasn't generally been a catastrophic problem. But when it comes to developing a system that needs to be opted into by 75 percent of all smartphone users, this presents a major challenge.

The latest version of its mobile OS, Android 10, is used by a proportionally low number of people. Google no longer publicly shows the breakdown of Android version use, but third-party statistics from StatCounter suggest that only around 31 percent of devices run Android 10, while 65 percent of devices in the US run Android 9.0 or later. Google told us that its contract-tracing system will be released through a Play Store Services update and will support all devices running Android 6.0 or later. This will cover, according to StatCounter, 94 percent of devices in the US or 91 percent of devices worldwide.

Apple does not have such a big problem. It has near-complete control over its devices, and just supporting back to iOS 13 would reach 80 percent worldwide, or 85 percent in the US.

As with Android, we have little more than anecdotal information about who is using what device, but a better sense of how many devices are at least capable of running which OS version. All iPhones newer than the 6S support the latest version of iOS, while the 6 and 5S are on 12.4 but are still receiving critical updates. We've asked Apple to clarify which of its devices will support contact tracing.

The issue with just looking at usage statistics is that they don't reveal the demographics that feed into them. As the gulf between US and worldwide figures suggest, the more affluent a person is, the more likely they are to have a recent smartphone or to have purchased a sufficiently high-end device that continues to be supported with updates. Anecdotally, it's probable that many elderly people, who are among the most vulnerable to COVID-19, are using low-end or outdated smartphones.

Apple and Google’s announcement looks to address two important challenges: making contact tracing available to as many people as possible and institutionalizing strong privacy practices. But it’s still unclear if people will opt in — both to the system and to the eventual public-health apps.

The main challenge here is not necessarily the tech — Apple and Google probably have more granular location data about us in their stores than a new system of Bluetooth signals would reveal. The challenge is to make the technology respectful of privacy, then prove it to enough people that 60 percent sign up. Everyone from hacker collectives to privacy advocates to new coalitions of technologists during the pandemic have listed their best practices for what that should look like.

We all have a natural incentive to comply with an ambitious public-health measure — to stay healthy and get the right people treated — said the ACLU’s Stanley. But to buy into a new level of surveillance takes the kind of public trust in the tech industry that has been eroding in recent times.

“This kind of approach cannot succeed unless it achieves wide adoption. And in a country like the United States, which is very suspicious of authority and government, being able to assure people that this is not any kind of broader tracking device will make it more successful as a public-health measure,” he said. “This is a situation where privacy and public health are very aligned.”

Aaron Souppouris contributed to this report.