How Electroloom's clothes-printing revolution died

The startup wanted to redefine how we made fabrics, but hype and reality got in the way.

What happens to all of those startups that get their five minutes in the spotlight before disappearing into the ether? In the hardnosed world of technology, a thousand such enterprises will fall before a single one becomes even a modest success. This is a story about one of those that didn't make it.

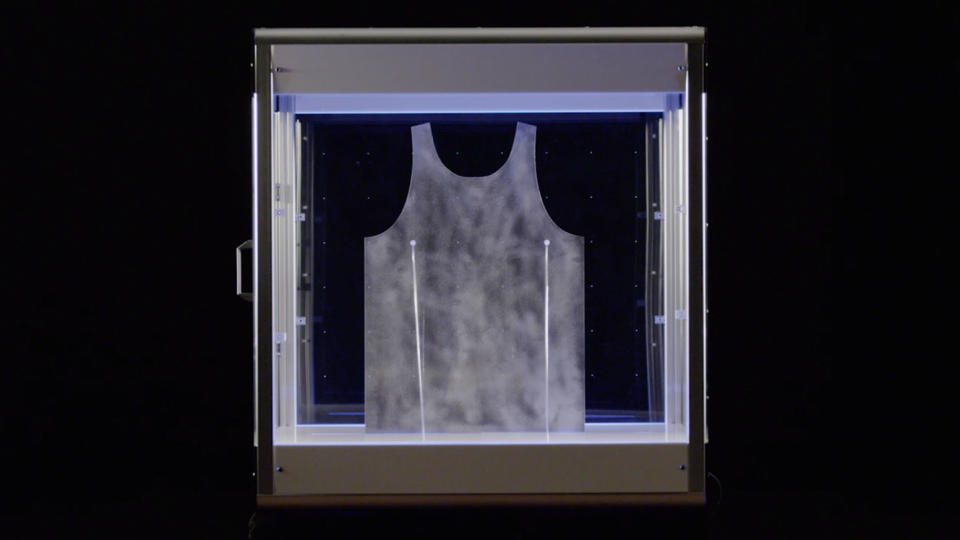

Electroloom launched back in late 2013, a radical device that had the potential to upend the world of clothes manufacture. The device could -- theoretically -- create a garment in any shape we saw fit using little more than electricity and raw materials. The 3D printer for clothes also created fabric without stitches or joins, making its products lighter and stronger than typical cloth.

And yet, just A couple of years later, Electroloom had run out of money, with investors abandoning the project. The dream had died as quickly as it had begun, leaving plenty -- including crowdfunding backers -- to wonder what exactly had happened. Now, a year later, company co-founder Aaron Rowley opens up about what went wrong and what killed the Electroloom.

It was at California Polytechnic State University that Rowley was first exposed to the process known as electrospinning. Field-Guide Fabrication Electrospinning, to use its full name, is a process used to make medical implants and air filters.

Imagine a sealed plastic box, with an electrically charged metal plate that can be any shape you desire. A customized mix of liquid polyester and cotton filaments is then sprayed onto it through an electrically charged nozzle. The airborne fibers are drawn to the plate and form as a series of nanofibers, gradually building into a single piece of cloth.

It's not all magic, however. For one thing, the process takes a very long time to complete: up to 16 hours for a single garment. Even though results were slightly crude, the lack of stitches and joins offered the possibility of new ways to create clothes.

Rowley's interest in the technique didn't start until after he began tinkering with 3D printing at night, after his day job at Boston Scientific. He soon found the technology too limiting, saying that, "conceptually, the world is not made of completely solid goods." Soon after, he decided that "rigid 3D printing isn't the Holy Grail," and explored other methods of creating objects.

It was a short step from there back to the experiments he had undertaken as an undergraduate in college. Electrospinning seemed, at first blush, like a way to break past the orthodoxy of existing manufacturing methods. He teamed up with Joseph White, another CPSU student and friend, to examine the wider potential for the technology.

But before Rowley and White could spend any time really looking into the research, they were thrust into the spotlight. In 2014, the pair applied for a design grant from Alternative Apparel, because the first prize was free access to TechShop, a maker space in San Francisco. They won, and in addition to unfettered access to the hardware space, they received another prize as well: attention.

"The reality is, everything just really snowballed. I had been messing around with it," says Rowley. "After we won, there was these investors that heard about it and started talking to us." He was caught up in a "wave of enthusiasm" that stopped him from having the time to "really sit and think: Is this the right technology?" He adds that "there were a lot of things that I think I didn't think enough about before really committing to it."

At the time, Rowley had little more than a document, some renders and a vision for how things would go. But he had optimistically promised that Electroloom would have a workable product within a year. By May 2015, the company had launched a Kickstarter designed to develop a number of prototype devices that could be used to finesse the product, much like Oculus' initial run of developer-friendly VR headsets.

That was when the problems really started to mount up.

"We were making such decent progress, and things were going so smoothly, that it felt reasonable to make certain assumptions." These included the idea that it would be easy to build a desktop Electroloom reliable enough to build a developer community. "The machine created big electric fields, which caused so many challenges from an electronics standpoint." Rowley explains that "our hardware couldn't withstand a lot of the fields that we were creating."

When they did manage to get the devices working, even more problems became apparent, including a terrible user experience.

In a regular 3D printer, a user can place a plastic filament into an extruder and, with some patience, get it working. But operating the Electroloom wasn't that simple, and Rowley "didn't really have a great user experience for putting chemicals into the machine." In fact, the team "couldn't get things to that baseline [level of] quality we thought we needed for people to really get value out of these developer machines."

And then there was the fabric itself, which looked great on the video and felt soft to the touch, like a form of suede. But when it was actually worn as a garment, it wasn't the most comfortable thing to have on your body for a whole day. "It held its tension, it had some ability to stretch and it did flow like a fabric," says Rowley. An early experiment involved a misshapen white T-shirt that was taken home by one of the Electroloom team. It was subsequently worn by the employee's daughter as a dress, and, Rowley admits, "the dress was a really exciting moment for us."

But the team's optimism quickly gave way to despair as they learned that the fabric, for all of its promise, wasn't working. "It would fray very easily, and layers would begin to fray from the surface," says Rowley, adding that "the edges would [then] begin to tear quite easily." There was also the fact that, while the T-shirts were strong enough to withstand being pulled around on camera, they were very vulnerable to snags and tears on things like door handles.

The team began tweaking the fabric to try and iron out these issues, but the various chemistries that they employed all had their own pitfalls. "If we wanted more durable, the fabric got stiffer and then it wouldn't flow," says Rowley, "but if we wanted it to be softer and similar to how clothes feel, then it got super weak." Later, "we could never figure out how to balance those two characteristics, no matter which way we tried to push it."

Unfortunately, this realization came long after the Kickstarter, as it dawned on the team that there were "certain [chemical] things we couldn't hack." And that the sort of resources required to make the process work would raise eyebrows at a chemicals behemoth like Bayer, let alone a tiny startup.

Then there was the fact that Rowley didn't really know what Electroloom was for, or who would wind up using it. The company's genesis occurred at the peak of the distributed manufacturing craze -- the notion that you'd 3D-print objects at home or locally, rather than import them from across the world. The hope and expectation was that the notion of the factory would die away in favor of the in-home replicator.

But the notion that we were a few years away from having a 3D printer to create any conceivable object in our homes was a laughable one. More reasonably, the sort of looms that Electroloom proposed would be better suited to mass-production factories. The move by shoemakers like Adidas and Nike to "reshore" their production to the West, facilitated by robotic factories, is clearly where the world is going.

Unfortunately, Rowley and, by this point, his team were trying to serve a wide variety of masters. The company had conversations with textile factories interested in building an industrial version of the device. The team was essentially offered carte blanche to build a device big enough to fill a warehouse, but had to pull out because some members couldn't countenance relocating.

Rowley admits that "the industrial route probably would have been better to focus in on in that capacity." Fundamentally, building a consumer device, initially for hobbyists, "added this huge, huge layer of complexity" that made finishing the job almost impossible.

On August 10th, 2016, just short of a year and three months later, Rowley posted the note "Thanks, and Farewell" to his Medium page. The money had run out, and while investors were supportive, fresh sources of funding were hard to come by. A variety of factors had played into the company's collapse: slow technical progress, scientific risk and a "poorly defined market opportunity."

In the postmortem, it's clear that Electroloom was hyped by its creators and those around them far too early. In the push to take a good, but nebulous, idea to market too soon, the endeavor wound up wasting plenty of time and money.

Electroloom is no more, and the underlying technology is trapped in limbo, gathering dust in basements both real and metaphorical. Rowley and White have both been forced to move on, the former joining Vue, a smart-glasses startup.

Rowley has advice for others looking to build their own hardware company off their own backs as well. "In software," he explains, "you might have a couple of developers who can handle an entire project." By comparison, when building a real product, "it's touched by hundreds of people," and one mistake by any one of those people can ruin things forever.

Vue is, however, benefiting from Rowley's scars, carrying over his experience of building hardware projects. The entrepreneur believes that he is "learning a lot that [he] wasn't learning," and that he will always take "more time with diligence on a product."

If he had the chance to do it all again, Rowley would have made a greater effort to examine different methods of creating fabrics. "We just made a bet on electrospinning way too early," he says, "but we got promising prototypes and we kind of just said, Okay, that's it." He admits as well that there was "a lot of naïveté on [his] part" as he bought into his own hype.

Rowley also believes that there is a problem with Silicon Valley's culture, which pushes an unhealthy view of business. He explained that investors and inventors aren't bothering to pay attention to what came before, "to understand what their technology should be doing." But the collective blindness to this is a result of the "hype around getting funded" and "stories glorifying founders like Mark Zuckerberg and other college drop-outs." He adds that Silicon Valley deserves "all of the criticism that it gets." Because, fundamentally, "it does a lot of great things, but it's also a culture where people get away with some ridiculous things."