You'll soon be able to get a 3D printed model of your brain

Oh this? It's just my brain.

There are almost limitless possibilities when it comes to 3D printing. Design your own color-changing jewelry? Fine. Fabricate your own drugs? No problem. Print an entire house in under 24 hours? Sure! Now, researchers have come up with a fast and easy way to print palm-sized models of individual human brains, presumably in a bid to advance scientific endeavours, but also because, well, that's pretty neat.

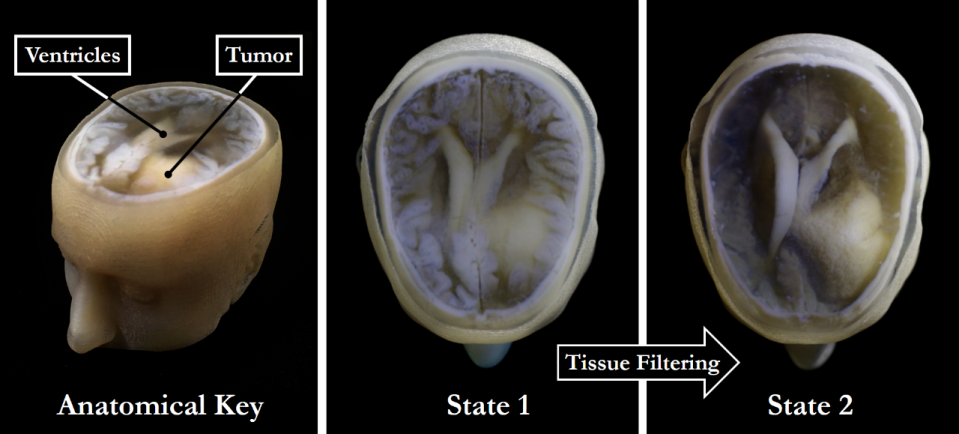

In theory, creating a 3D printout of a human brain has been done before, using data from MRI and CT scans. But as MIT graduate Steven Keating found when he wanted to examine his own brain following his surgery to remove a baseball-sized tumour, it's a slow, cumbersome process that doesn't reveal any important areas of interest.

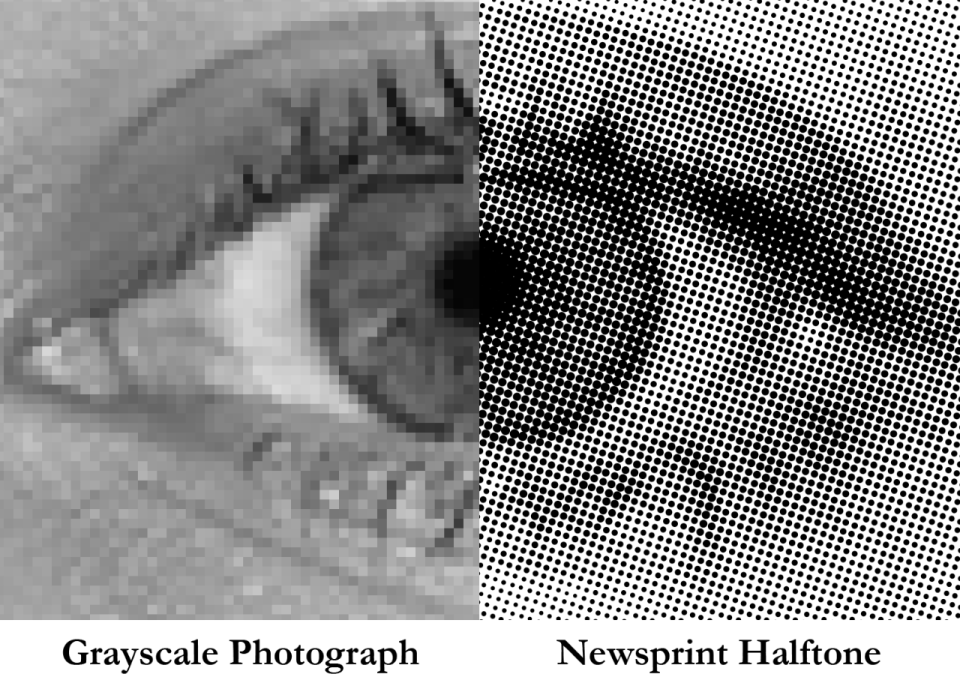

MRI and CT scans produce images with so much detail that objects of interest need to be isolated from surrounding tissue and converted into surface meshes in order to be printed. This involves a radiologist manually tracing the desired object onto every single image "slice" of the brain, or it can be done via automatic thresholding, where a computer converts areas that contain grayscale pixels into either solid black or solid white pixels, based on a shade of gray that is chosen to be the threshold between black and white. But since medical imaging data often contains irregularly-shaped objects and lacks clear borders, features of interest are usually over- or under-exaggerated, and details are washed out.

The new technology, developed by Keating and a team at Harvard's Wyss Institute, relies on printing with dithered bitmaps, a digital file format where each pixel of a grayscale image is converted into a series of black and white pixels, and the density of the black pixels is what defines the different shades of gray, rather than the pixels themselves varying in color. It's like the way black-and-white newsprint use different sizes of black ink dots to represent shading.

The result was a 3D model of Keating's brain that preserved all the detail shown in the MRI data, down to a resolution that's on par with what the human eye can see from about nine inches' distance. The team has applied the same approach to other parts of the body, too.

"Our approach not only allows for high levels of detail to be preserved and printed into medical models, but it also saves a tremendous amount of time and money," says James Weaver, who also worked on the project. "Manually segmenting a CT scan of a healthy human foot, with all its internal bone structure, bone marrow, tendons, muscles, soft tissue, and skin, for example, can take more than 30 hours, even by a trained professional. We were able to do it in less than an hour."

The team hopes that the technology will be employed in hospitals for routine exams, diagnoses and learning, bypassing the time and expense previously involved in 3D printing medical imaging sets. "I imagine that sometime within the next five years, the day could come when any patient that goes into a doctor's office for a routine or non-routine CT or MRI scan will be able to get a 3D-printed model of their patient-specific data within a few days," says Weaver. Or in other words, you'll be able to walk around with a true-to-life model of your brain in the palm of your hand. Neat.