PS4's 'Detroit' doesn't take place in the Motor City I know

It's an approximation, not a recreation.

When Sony debuted Detroit: Become Human at E3 two years ago, writer-director David Cage said he and his team were taking great care to respect Motown's heritage, its people and what they've been through. "When you set your story in a specific city, it's a very sensitive thing to do," he told me. "You don't want to do it if you're not respectful of the place, of the people living there." I've seen how games like Persona 5 and the Yakuza series have faithfully reproduced their Japanese settings, and I was excited to explore his digital Detroit. Unfortunately, my expectations were set too high.

After spending so much time in Detroit over the past five years, it feels more like home than my city of Grand Rapids ever has. I didn't expect something like Rockstar Games' painstakingly-detailed yet fictional take on New York City from Grand Theft Auto IV. Or hell, Watch Dogs' sterile Chicago. Instead, I was just hoping Detroit wouldn't be another Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, using Detroit's name and hardships as shorthand for "destroyed city."

Detroit's high-level depiction of the downtown area is recognizably Woodward Avenue, even if it isn't a 1:1 replica. TV spots for the game proudly include the Monument to Joe Louis and Spirit of Detroit sculptures, downtown's retail district and monorail system, and to balance out the glitz, blighted houses. The full game has all these and more, including a few extremely subtle (but welcome) nods that'll be lost on anyone not familiar with the region.

For example, instead of licensing any of the names or logos for the city's sports clubs, Cage's Quantic Dream studio came up with its own nomenclature. While the Gears might be a simple replacement for the real-world Pistons basketball team name, Detroit's hockey team's name -- the Crimson Sharks -- is anything but.

The real city's graffiti scene is incredibly vibrant, and art has been used to combat gangs tagging their turf. Its Eastern Market neighborhood is covered thanks to an all-mural street-art festival and the nearby Red Bull House of Art's program that offers live-in residencies to artists from around the world. None of the works are more striking than the pair of great white shark murals, each painted with a deep shade of red by artist Kelly "Shark Toof" Lund.

In a further tribute to aerosol artistry, one section of the game even has you scanning graffiti in post-war residential suburb Ferndale for a hidden path to the android safe-haven, Jericho. Adjacent to one of Detroit's coded maps is a black-and-white bust of a great white shark. Clearly, the aquatic apex predators adorning the Motor City's buildings made an impression on Quantic Dream.

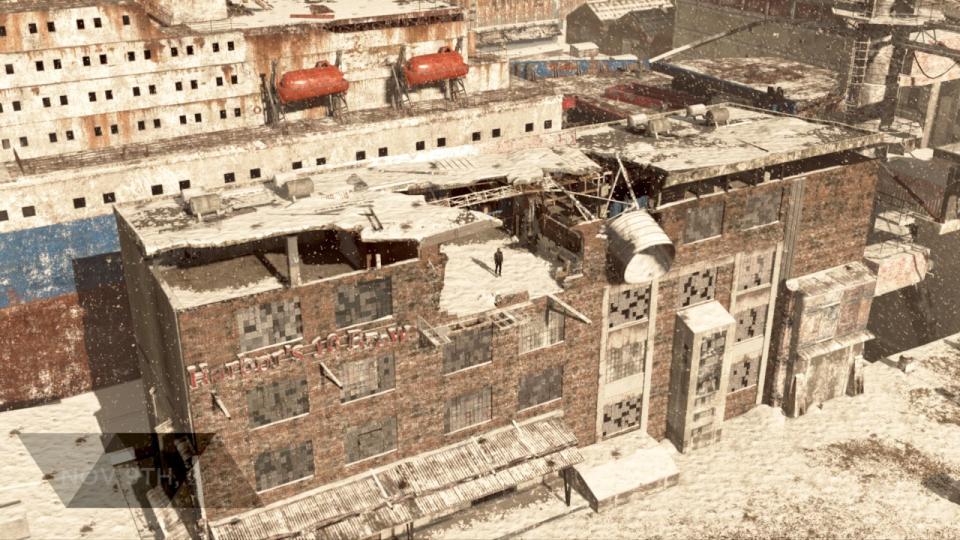

Another scene features a rooftop chase through an urban horticulture facility, showing how far the movement to transform empty city blocks into sustainable farming could progress. It's too bad the D's geography wasn't treated with the same attention to detail as its culture.

In a lot of ways, it seems like Cage took notes about Detroit iconography on loose leaf paper during location scouting and had to hastily reassemble them when he began working on the game at home. It'd explain why the abandoned factory housing Jericho (where androids can live unshackled from their owners) is in Ferndale of all places, a low-crime suburb known for picket fences and funky local shops, not crumbling manufacturing facilities.

The unfortunate side effect of this is that the game suggests Detroit's infamous urban decay that was splashed across numerous magazines and websites in the mid-2000s stretched even further than it did in reality. Jericho would be a much more natural fit 10 miles southeast in industrial borough Hamtramck, where the cavernous, deteriorating Packard Automotive Plant is located.

Cyberlife, the world's first trillion-dollar company, is responsible for creating the game's androids, and its headquarters reside on Belle Isle, a thousand-acre island located in the Detroit River, between Michigan and Ontario, Canada. In reality, the sprawling state park is home to an aquarium, conservatory and a museum dedicated to the Great Lakes, among other attractions.

It's hard to imagine Detroiters getting on board with turning the park into a campus for a mega-corporation, but it wasn't too long ago that Libertarians proposed buying Belle Isle for $1 billion and turning it into a free-market utopia with its own currency, the Rand. Since Detroit is set in a fictional future, versus the present like Yakuza and Persona, perhaps Cage's vision is one where part of that came to pass.

It's these types of inconsistencies that rob Detroit of its authenticity, and as a result, a lot of character. The game's licensed soundtrack is comprised of bands hailing from Motown, and the in-game Detroit Today newspaper is a knowing wink to the Detroit Free Press, which is owned by USA Today publisher Gannett. But for as much as I appreciated those bits of world-building tucked away in the background I was baffled by inconsistencies in the broader aspects that everyone will notice — not just lore nerds like me.

Folks outside of Michigan likely won't take issue with these inaccuracies, but they still exist, just like Cage's platitudes about respecting Detroit and its people.